Frank Stella has always been a jazz fan. His earlier work was positively influenced by jazz music which was visible in his paintings and all that peculiar dynamics. Similarly to jazz patterns, when rhythm goes syncopated beats, the composition in Stella’s 1964 work “Hyena Stomp” may seem a little twisted. And yet beautifully off-beat.

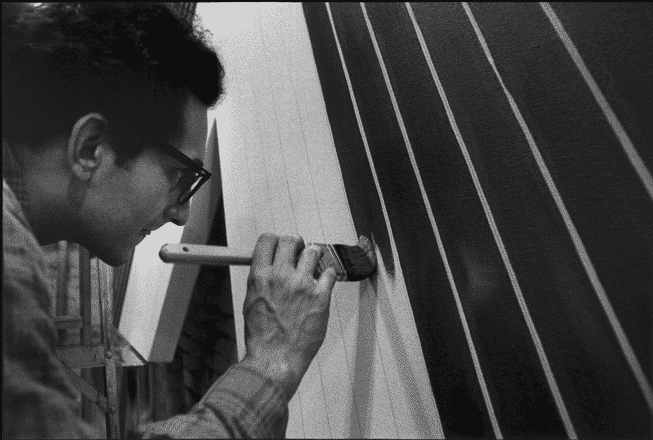

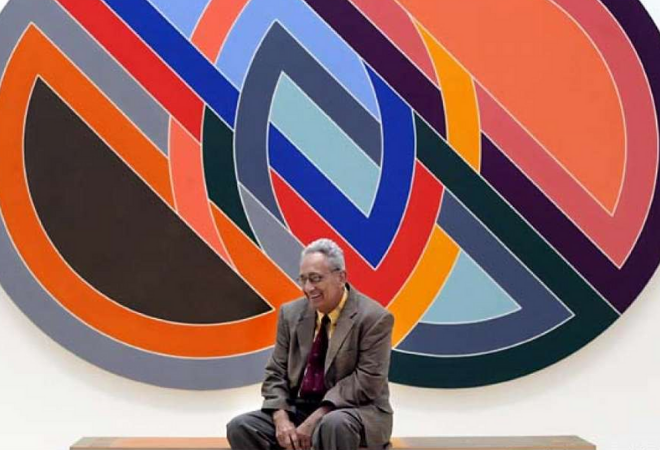

It wasn’t once that a single expert or a layman glance at Stella’s work resulted in an underwhelming impression and an even more disappointing reaction. Even Stella himself made fun of his approach: “I’m more of a house painter. That’s how I work.” While some things he did may look strange, but – like it or not – Stella’s relentless experimentation has made him one of the most important artists of 20th century. His work has influenced important artistic movements like Minimalism, Post-Painterly Abstraction, and Color Field Painting. And at the age of 82, he’s still rolling.

From Painting Houses and Boats to the Museum of Modern Art

It all started in Malden, Massachusetts where Stella was born May 12, 1936. His father who was a physician insisted on education, but he also wanted to show young Frank the importance of manual labor. Painting their house and recoating his father’s boat were his first encounters with a brush, and, in lack of a better word – Art. Technically, Frank Stella has been painting pretty much ever since he can remember. Bartlett Hayes Jr., the gallery director of the Addison Gallery of American Art and an abstractionist and Stella’s art teacher, Patrick Morgan helped him take his skills to the next level of abstract art when the young Stellar studied at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts.

Later, Stella continued his art education at Princeton University, where he earned a degree in history. A painter Stephen Greene and an art historian William Seitz, who were his college professors, influenced his early aesthetics by introducing him to the New York art scene. After graduating, he moved to New York where he set up a studio in a former jewelry store. A true artist in his core, the moment he arrived at the Big Apple, he knew what he wanted. His visits introduced him to early modernists like Jackson Pollock but particularly admired German Bauhaus exponents like, Franz Kline, Hans Hofmann and Joseph Albers. Stella was also influenced by European masters during this period, such as Picasso, Matisse, Malevich, and Mondrian. And ever since he realized painting was his passion and his primary mission, he set out on a journey of self-upgrade, looking to reach their level, or even surpass them.

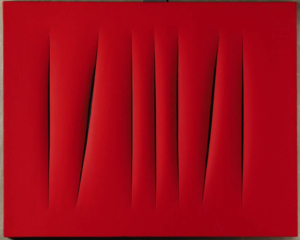

Right away, Frank attracted attention with his “Black Paintings” series. He used only one color black, repeated geometric patterns, separated by thin lines of unpainted canvas. With “Black Paintings” Stella wanted to move on from abstract expressionism to the radical next thing, claiming that “a painting is a flat surface with paint on it, nothing more.” He surely did move the visual art in another direction. He was only 23 years old when The Museum of Modern Art recognized his talent and purchased one of his paintings as a part of their permanent collection.

A Sculpture Is Just a Painting cut out and Stood up Somewhere

His restless spirit and attraction to innovation have been the unstoppable force that drove him forward. Soon, Stella abandoned the classical rectangular format of the canvas and created shapes, embracing more complex motifs and brighter colors. During this period he expanded his interests by delving into printmaking, which he continued later throughout his career. The most significant works from this period are “Aluminum Paintings” (1960), “Copper Paintings” (1960-61), “Irregular Polygon” (1965-67), and “Protractor”(1967-71) series.

From that point on, there was no stopping for Stella. He didn’t even turn around to admire his work, and enjoy the ovations – all he wanted was to create, and create some more. In 1970, Stella became the youngest artist to have a retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) – a success, the majority of artists would kill for. But, not everyone admired Stella’s groundbreaking work. The New York art critic Michael Fried, who was mentored by none other than Clement Greenberg, said that he should stop painting when he saw Stella’s works from the early ‘70s, while a fellow painter Ken Nolan declared Stella’s Lipsko III “the worst thing he has ever seen.”

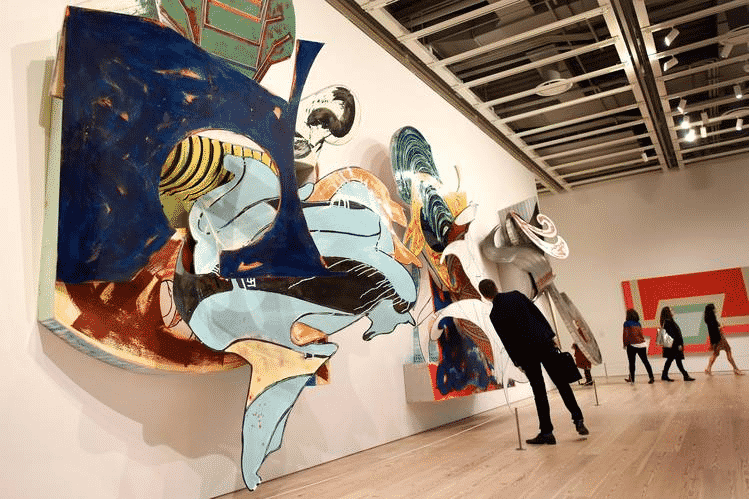

Being primarily an art lover, Frank Stella never cared about what others thought and continued. With Stella, breaking artistic boundaries has never been intentional: it was more of a personal reflection on what he sensed and felt, a moment in time he needed to represent in color and shape. For his “Polish Village” series he attached paper, wood, and felt to the canvas while for the “Indian Bird” series, he painted on aluminum forms that were hanging from the walls. His paintings were becoming more three-dimensional, but he never considered them sculptures: “A sculpture is just a painting cut out and stood up somewhere.”

Further Evolution and Embodying Architecture

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, Stella continued expanding his 3D paintings. They became more vividly colored, multifaceted, and experimental. He applied all the techniques he’s ever used on his series based on Herman Melville’s novel “Moby-Dick.” Like the majority of artists, Stella was never fully satisfied with his creation which took him to expand his work to architectural structures. All of the different approaches and techniques along with his future interest in architecture seemed normal to him: “It’s hard not to think about architecture when you’ve gone from painting to relief to sculpture.” Among these works is an aluminum band shell in Miami (1999) and a gigantic sculpture, Prinz Friedrich von Homburg, Ein Schauspiel, 3X (1998-2001), placed on the lawn of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Today, Frank Stella is living and working in New York, still making sculptures and architectural projects.

Tireless Traveling into the Unknown

“The integrity of being an artist for Frank means going into the unknown,” said Adam Weinberg, director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, where Stella had a retrospective exhibition in 2015-2016. And he did indeed go into the unknown. He never settled – never satisfied. Stella always wanted to do something else, something new. It has always seemed like he had planned his next move before even finishing what he had started. He once said: “I get cranky real easily. So the honor of it and the wonder of it all and everything has a hard time overcoming the petty annoyances. I mean, that’s simply the reality of being alive, I guess.”

Playing with dynamics, shapes, and colors, fighting boredom, and being curious, Frank Stella became one of the greatest living artists. He affected many contemporary artists and their artistic styles and genre. His “Black Paintings” series, stripped of any meaningful content, secured him a spot in history books, while his more recent accomplishments still need time to be entirely grasped. And, there’s no doubt, as long as he lives and breathes, Frank Stella will keep experimenting with the exhilarating world of artistic imageries in new dimensions, keeping us on our toes for everything that’s going to come next.

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)