For 750 hours, Marina Abramović sat in a chair and stared at strangers. It was 2010 and this feat of endurance was part of her retrospective, The Artist Is Present, at MoMA. Thousands of people eagerly queued up for the privilege of staring back at her. A retrospective is a particularly interesting venue for a piece of performance art—performance art is, by definition, a live event. What can even be included in a retrospective? Consider some of her other pieces—driving in a circle for 16 hours, standing nude in a doorway and forcing members of the public to squeeze past (performed with Ulay), and walking from one end to the middle of the Great Wall of China and back (also with Ulay). How do you put those in a retrospective? How do you create a record of them at all?

Why Should We Archive Performance Art?

Archival is about creating a record of a work of art with all the pertinent information about it. We archive our art so that we have a complete record of the paintings, sculptures, drawings, and other artworks we create. We expect to hold onto those pieces and we don’t want to forget anything about them.

Performance art, of course, is different. It doesn’t go on the wall or even into storage (if only we had bigger apartments with more wall space!). Instead, it’s meant to be ephemeral. Almost by its nature, it defies conservation. Performance art is about experiences and not objects. For some, it’s an explicit rejection of the objectification of art. Is it sacrilege to archive performance art?

There may be some performance artists who object to archiving on the basis that they want their pieces to be one-time events experienced in the moment (Tino Sehgal, for example), but it’s not inimical to the concept of performance art. Like all art, performance art is about sending a message. Like all artists, performance artists develop and change over the course of their careers. Without archival, that valuable history is lost. For developing artists, an archive is the start of your portfolio—with a complete record of each performance, you can pick and choose the ones to include in your portfolio for a given curator or gallery.

Performance art can be fleeting—if anything that takes more than 700 hours can be considered fleeting —but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be remembered and preserved. Archival also democratizes performance art. Should you be shut out of viewing The Artist Is Present just because you didn’t live in New York or have time to spend hours in line? An archive can let the public into the performance art world, giving the artist a wider audience and the audience a wider perspective and new experiences.

How Can We Archive Performance Art?

The answer to this one may seem obvious—videotape it! It’s possible that that makes sense for Marina Abramovic’s The Artist Is Present, even if that’s a very long videotape. However, consider Rirkrit Tiravanija’s 1990 piece at the Paula Allen Gallery, entitled pad thai. He cooked and served food for visitors to the exhibition. A video could certainly capture some of that piece, but not all of it.

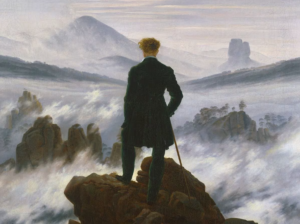

So, our archive needs more information. As with archiving conceptual art, the best way to archive performance art is going to depend on the specifics of the piece. A video is often going to be a good place to start, as is a written description of the piece for context. From there, we get into specifics. A record of pad thai, for example, might include the recipe Tiravanija used. Or consider Chris Burden’s piece, Trans-Fixed (image above), in which he was nailed to the roof of a Volkswagen Beetle. An archival record might include information about where the piece was performed, who else was involved, and other details.

Archiving Art Is its Own Artistic Challenge

Until we have perfected the art of virtual reality (including smells, especially if the smell is pad thai), we won’t be able to create a record that allows a viewer to experience performance art firsthand. In that sense, performance art can’t truly be preserved beyond the original performance. When we archive performance art, however, we create a set of mementos that help us remember our experience of the piece and help convey some of that experience to those who didn’t have the opportunity to witness it firsthand. Creating that record is valuable with any kind of art, but especially so when the work is fleeting.

Performance art is a challenge both to the artist and to the audience. Creating an archive of performance art is also its own unique challenge to the artist, collector, curator, and art enthusiast. What information gets at the essence of a given work of performance art? What is crucial to the artistic intent? The process of archiving art forces the archivist to dig deep into the significance of the artwork and distill out those pieces that are necessary to the whole. It’s not always easy, but it gives you a new way to engage with the piece as well as preserve it for posterity. So roll up your sleeves, dig out your notebooks and cameras, and rise to the occasion!

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)