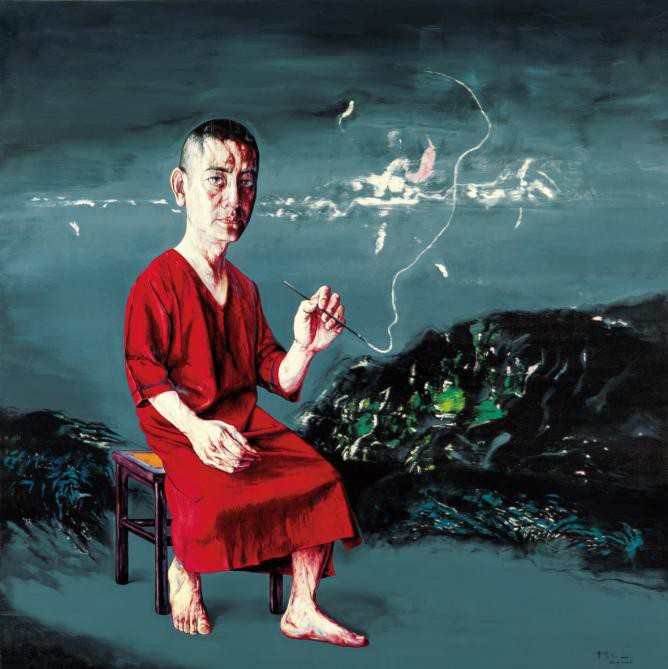

Not often do we get to be in the presence of majestic introspection beautifully communicated through color, shape, line, and idea on canvas, but when we do, it’s usually spelled: Zeng Fanzhi. What we used to (and still do) admire about Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and other great contemporary painters in the context of the Western world, we now do about Zeng in the context of the Eastern. When it comes to Zeng’s work, what at first glance looks like chaotic strokes by brushing and splashing paint, quickly (and easily) turns into meaningful, and elaborate artwork, a specific fusion of optimism and irony, uncertainty and revolution. Everything our favorite Chinese maestro does resonates with intense emotions, and deliberate critiques of the current, popular (self) destructive momentum. Zeng’s brushstrokes and figurations are relentless, vivacious and wholehearted intentions that end up being not only our soul food but a timeless message, an asylum from things that suffocate us in the 21st century.

How Things Started

Born in 1964, Zeng is from a generation that sits on a cusp in Chinese history. The artist remembers the feeling of social control at the time of Cultural Revolution, but he also recalls he was too young to participate in China’s rollicking 1980s. Even so, his artistic drive kept him going. Zeng has always been the one to see beyond the social oppression into the more significant truth – one liberated from emotional and social tyranny, the truth that meant awakening.

The fact Zeng didn’t get into Hubei Academy of Fine Arts at the first try still gives hope to a number of artistic souls that are struggling to have their talent certified. Waiting for another turn, Zeng spent his early twenties working in a printing press. However, the moment he got in, there’s was no stopping of his talent, diligence, and commitment to turn his vision into visual representations of the truth as he saw it. He would spend all hours he could at the school’s library or absorbing information from his teaching masters. Zeng dearly remembers an encyclopedia of Western art history that taught him to admire figures like Ernst, Beckmann, and Schiele.

The strongest influences visible in Zeng’s work link to German Expressionism. This kind of aesthetic is predominantly visible in his signature expressionistic paintings that ooze a peculiar psychological tension combined with an almost palpable, underlying angst. Zeng’s work is more about what we feel than what we see. However, despite his predominantly difficult motifs, none of them lack beauty.

Zeng’s Earliest Works

The early works of Zeng Fanzhi’s opus were marked by the exploration of apocalyptic scenes and a very sleek but obvious manipulation of modernist compositional effects with the purpose of intensifying the artist’s version of reality. The artist’s canvas usually explores the depth of the unconscious in the construction of experience. The subjects’ hands are often clenched and over-sized, and if possible even more outstanding than their wide-open eyes and stereotyped faces —also evidenced in the “Self-Portrait 09-8-1” of 2009, featured below. The message of his work is unequivocal: the contemporary experience of excessive consumption is, in lack of a better word, disgusting and leads to detachment, alienation, and loss of identity.

Following the Tiananmen protests of 1989, Zeng’s work boldly explored the upsetting goings-on of the time, and in doing so attracted a number of local critics and curators who were more than willing to give Zeng’s work a thorough overview.

Just as we’re used to having it happen in artistic circles, that is – with the artists who know they want to go from a no-name to the hottest artist of the moment – Zeng went against the norm of the time and rejected to paint shepherds and peasants on China’s rural periphery for his graduation project. Instead, he created a hospital-inspired triptych (featured above), arranging it in a way it channels Western religious paintings and a very familiar artistic tension of a young painter finding his place in a turbulent society. It wasn’t long before Zeng was included in the January 1993 exhibition “China’s New Art: Post-1989.” This happened shortly after he had sold his first painting. Soon after, Zeng moved to Beijing (in the early 1990’s) gradually immersing himself in the capital’s vibrant art scene. It didn’t take long for the artist to realize the pretensions and façades of the big city and all the success that comes within it.

What is more, his best-known works – the “Mask Series” – go back to this period. This series began as a reaction to the artist’s devastating feelings of solitude, social isolation, and the inability to find honesty and truthfulness in the busy city of Beijing. In a word, “Mask Series” represent Zeng’s existential concerns. He started working on the Mask Series in 1994.

The Constantly Evolving Beauty of Zeng’s Artistic Sensibility

In the quarter-century the artist has spent in Beijing, his style has continuously evolved. Luckily for the admirers of his work and the entire art industry alike, Zeng cultivated a distinct manner of shifting artistic gears: unlike many of his contemporaries, Zeng never stays safe in his expression but pushes the envelope to the point of radical, even confusing to some. Over time, he has become an expert in juxtaposing naked, exposed human fears and the society in its worst or – better yet – in its most real. This is possibly best seen in his Hospital Series where he contrasts the horror of bureaucracy and distraught patient and doctor as human anguish while using muted tones to portray an apparent decay of the crowds. To Zeng, painting and psychology go hand in hand which is why we see such a blunt, open critique on of the often unfair reality portrayed in his works.

In the early 2000s, Zeng’s artistic style took a turn from his piercing German expressionism and turned to somewhat softer, traditional Chinese influences, much of it taking inspiration from the landscape paintings of the Song Dynasty. This dramatic shift in technique and thematic focus was evident and it quickly and unsurprisingly transformed to landscape art (no wonder Zeng’s lawn is always oh-so-green). Some critics argue the artist’s piqued exasperation with the city caused this shift and led to his need to turn to nature which would, besides, align perfectly with the Chinese philosophy of happy existence. It is in the essence of Chinese culture the understanding that there’s nothing more significant than the Universe; therefore, the “followers” of this philosophy cultivate a very conscious and respectful awareness for the magnitude of Universe and its power while, at the same time, keeping themselves modest and wide-awake in the present moment. Zeng’s striking landscapes showcase the all-pervading gulf between the reality of the environment and individual cognition. Painting simultaneously with two brushes, the artist manages to describe two subjects, each with a unique attempt and realization. Even in his landscapes, Zeng leaves elements of the subconscious visible, turning them into almost abstract fields.

A Cunning Approach

The 21st century is the era of openness, acceptance, and chance. There are more and more artists stepping on the scene, so one has to be very special to keep their position intact. Zeng is definitely one of the special ones, but when asked how he has managed to stay at the top, he said most of it lies in his cunningness to recognize people who actually love and understand his art. “I only sell my paintings to those who genuinely like them. Then those people will help me promote my works.”

Zeng’s undisputable painting skills combined with his approach of cultivating collectors who cherish his art may be what has propelled him to the fore, at least judging by Philip Tinari’s, the director of the Ullens Center, thought.

Furthermore, despite numerous Chinese artists roaring onto the international contemporary art scene in the past decades, not many have exhibited the staying power of Zeng Fanzhi. Better yet, none have matched $23.3 million, the price paid for his version of “The Last Supper” in 2013, at an auction.

Final Thoughts

Even though Zeng’s works are often seen as communicators of socially-conditioned human suffering (for the most part), to him – his works represent meditation – not suffering. Galleries and museums all over the world show his work, with eager art-enthusiasts lining up to enjoy ‘the show.’ With little dispute, Zeng is considered one of the best contemporary artists of Chinese origin.

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)