Why do the world’s most elite and wealthiest give the arts hefty amounts of money? Maybe they are passionate about preserving works for generations to come. Perhaps they want to direct their charitable giving to a more tangible cause. Or maybe having a wing named after them in an institution frequented by the public is how they can secure a legacy.

Whatever the motivations for philanthropy, museums and other art organizations will rarely ever deny a donation. After all, most art institutions are non-profit; therefore, they need funding to survive. Museums need financing to operate, preserve artwork, manage security and visitor traffic, and maintain the facility.

But what happens when a charitable family that has donated millions of dollars to museums all over the world becomes embroiled in more than 1,500 lawsuits and associated with hundreds of thousands of deaths? Does the art world ignore the philanthropist’s problematic reputation and continue accepting gifts? Or does it take an ethical stand and forego donations to cut ties?

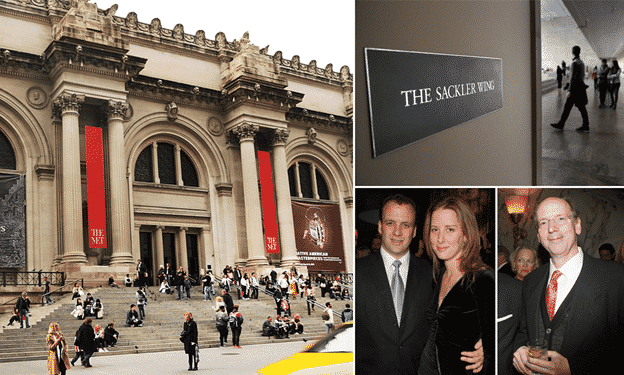

Such is the case with the Sacklers, as their family’s business history and role in the opioid crisis now creates the fault lines between philanthropy and ethics.

Who Are the Sacklers?

The Sacklers are an American and British family that rose to power as the founders of the pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma. In 1996, Purdue Pharma introduced OxyContin, a time-release version of oxycodone prescribed for severe and chronic pain. By 2015, the Sackler family was listed in Forbes as one of the wealthiest families in America.

With a net worth of reportedly $13 billion, the Sackler family supported the arts and education with multiple multi-million-dollar donations to major cultural institutions and universities. In the UK, the Sackler’s have made substantial donations to the Royal Ballet School, the Royal Opera House, the National Theatre, Old Vic, Royal College of Art, and so much more.

You will find the Sackler Library at Oxford. Tate Modern has a Sackler Escalator while the City & Guilds of London Art School has the Sackler Library. In 2017, the Victoria and Albert Museum unveiled its newest addition, the Sackler Gallery which reportedly cost £2 million. There’s even a stained-glass window named for Dr. Mortimor Sackler at Westminster’s Abbey.

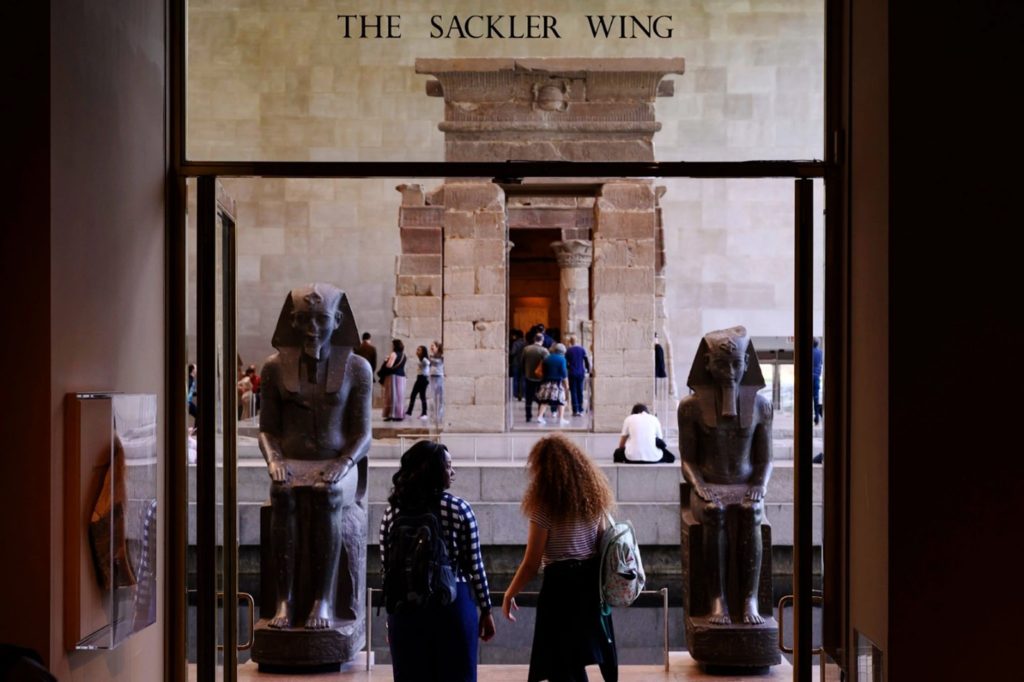

In the US, you will find the Sackler Institute at Columbia University. There’s the Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics at the American Museum of Natural History, the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution, the Sackler Center for Arts Education at the Guggenheim, and the Sackler Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and other places.

The Sackler’s initiatives aren’t limited to US and UK cultural institutions; you will find the Sackler Wing of Oriental Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris and the Sackler Staircase in Germany’s Jewish Museum Berlin.

However, as America’s opioid epidemic spread and decades worth of statistics backed the gravity of the crisis, the Sackler family found itself under international scrutiny and the subject of a massive lawsuit.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 47,000 Americans died as a result of opioid overdose in 2017 alone. In 1999, just three years after OxyContin was introduced, there were 3,442 overdose deaths involving prescription opioids. That number continued to rise year after year. By 2017, there were 17,029 overdose deaths involving prescription opioids.

The lawsuit involves more than 500 cities, counties, and tribes from all across the US. Eight members of the Sackler family are accused of deceiving doctors and patients and downplaying the dangers of OxyContin, which has led to the over-prescription and misuse of the drug.

Had one of the most philanthropic families in the world misled the public by withholding the truth about their drug? Did they profit billions from OxyContin prescriptions, while the painkiller allegedly took hundreds of thousands of victims?

The Sackler family and Purdue Pharma denied the allegations. Yet the court filing cited differently.

Philanthropy, Profits, and Power

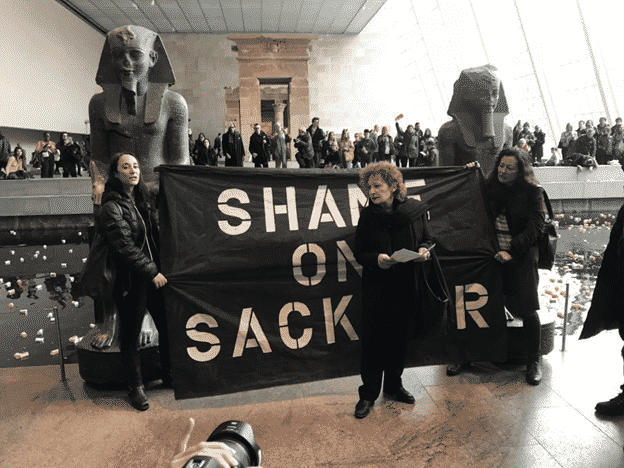

On February 9th, 2019, the front steps of the Met were filled with dozens of protestors carrying banners and chanting messages like “Shame on Shackler,” “Shame on the Met,” and “200 DEAD EACH DAY.” The group was led by photographer Nan Goldin who started Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (PAIN). Goldin and the members demand the removal of the Sackler name from museums and other cultural institutions, asserting the family is responsible for the opioid crisis.

On March 18th, 2019, the lawsuit representing 26 states and eight tribes against the Sackler family was filed in New York. In the same month, the National Portrait Gallery in London became the first to distance itself from the now infamous Sackler family. The institution and the Sackler family “jointly agreed” to return the £1 million donation from the family. While the decision was released to the public as a mutual agreement by both parties, it was clear that protestors like Goldin’s campaign was a catalyst.

Also in March, the Tate gallery group in London, comprised of London’s Tate Modern and Tate Britain galleries, Tate Liverpool, and Tate St. Ives, announced that they would no longer accept gifts from the Sackler family. In the past, the Sacklers have donated about $5.3 million to the group. There was an additional $1.3 million donation planned that will no longer push through following the announcement.

Tate explains the decision in a statement, “The Sackler family has given generously to Tate in the past, as they have to a large number of UK arts institutions. We do not intend to remove references to this historic philanthropy. However, in the present circumstances, we do not think it right to seek or accept further donations from the Sacklers.”

On May 15th, 2019, the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced that it would no longer accept donations from the Sackler family. Though the Met has a wing named after the Sacklers, the museum says they have no plans to remove the Sackler name, despite the ongoing protests. The Met’s president and CEO Daniel Weiss said in a statement, “In consideration of the ongoing litigation, the prudent course of action at this time is to suspend acceptance of gifts from individuals associated with this public health crisis.”

This decision aligns with an interview the Met’s new director Max Hollein gave Artnet News on September 2018, before the height of the protests and the lawsuit against the Sackler family. Hollein talks about the Met’s need to be “morally sublime” and how it should secure its funding “based on a clear set of values.”

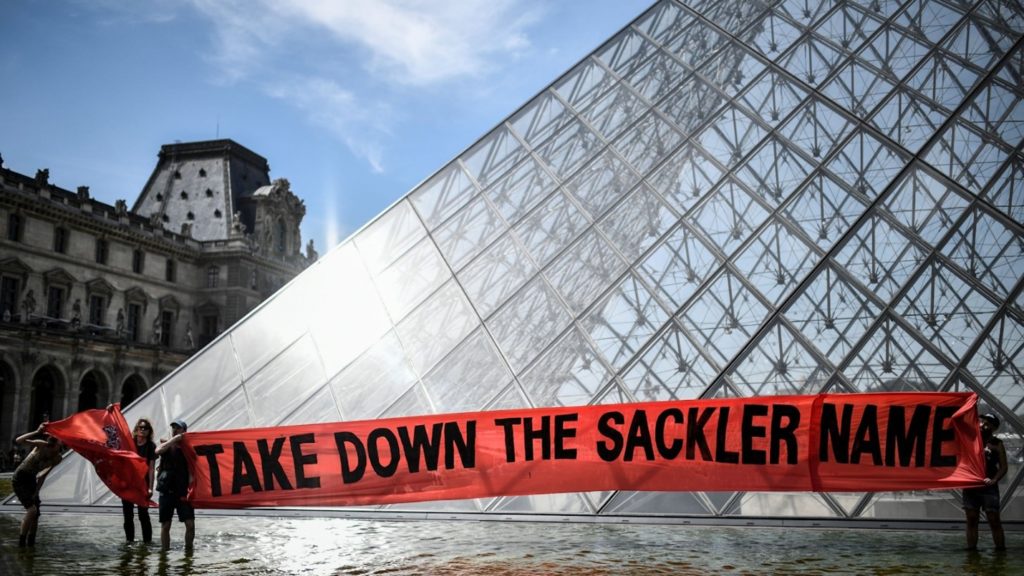

By mid July 2019, the Louvre Museum in Paris had removed the Sackler name from the Sackler Wing of Oriental Antiquities and became the first major art institution to remove the family’s name. A marked contrast to the US counterparts with much larger health crisis to Franceand European nations.

The Sackler case heightens inevitable scrutiny on closely tied livelihood of arts institutions with a small circle of philanthropic donors, to rethink and reawaken their ethical boundaries. Navigating moral dilemmas and rebalancing act in a challenging political climate takes more than courage as leading cultural institutions. In the end, the existence of art institutions has been and always will depend on the public’s participation that comes under watchful examination and the enjoyment that fills their buildings and exhibition halls.

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)