Recently, the Sorol Art Museum in Gangwon Province in South Korea opened its doors to the public, showcasing its eagerly awaited architectural design by Meier Partners. The inaugural exhibition features the works of the art master and father of Spatialism, Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), marking a historic moment as his art exhibits for the first time in South Korea.

Curated by the Lucio Fontana Foundation in collaboration with the Korean Research Institute of Contemporary Art, the exhibition showcases 27 works from the artist’s collection. The carefully orchestrated ensemble provides audiences with profound insight into Fontana’s exploration beyond the constraints of traditional media, materials, and methods. The exhibition takes audiences on a journey through Fontana’s evolution and innovative interpretation and demonstration of spatial concepts.

Across Continents and Art Movements

Lucio Fontana was born on February 19, 1899, in Rosario, Argentina to immigrant parents of Italian descent. In 1905, his family moved back to Italy, settling in Milan. In his late teens, Fontana volunteered for the Italian army during World War I, reaching the rank of second lieutenant. In 1918, he was discharged with a silver campaign medal after being wounded. In the early 1920s, Fontana studied at the Accademia di Brera where he initially trained as a sculptor, focusing on traditional techniques. He studied under the sculptor Adolfo Wildt, an Italian sculptor known for his symbolic and expressionist sculptures. However, Fontana soon became interested in painting, experimenting with various artistic styles and progressing with a unique artistic vision.

By 1926, Fontana emerged on the artistic stage with his participation in the inaugural exhibition of Nexus, along with other independent Argentine artists. Fontana was associated with various avant-garde movements by this point. Influenced by the emerging Futurist movement, Fontana participated in exhibitions with art that aligned with the political ideologies of the time.

In the 1930s, Fontana’s artistic compass pointed him toward Argentina, where he immersed himself in sculpting and molding. By the time he returned to Milan in the 1940s, Fontana had already become a prominent figure in the art scene. He also taught at traditional art schools and co-founded the Altamira School of Arts in Buenos Aires in 1946.

Artistic Odyssey and Aesthetic Innovation Through the Concept of Space

While Fontana was a professor of sculpting, he promoted innovative thinking to his students, encouraging them to embrace conceptual approaches to art. Under his direction as a teacher at the school, students published “Manifesto Blanco” (The White Manifesto), a pamphlet articulating the aspirations to create “spatialist” art and the integration of other elements into conventional art, particularly contemporary technology and architecture.

The aftermath of World War II had created an atmosphere for expression and artists eagerly sought ways to move beyond traditional artistic boundaries. Fontana’s fascination with the concepts of space, space travel, and space-age aesthetics set him on a quest to discover the unknown dimension, an interest that likely began when the first-ever photos of Earth taken from a rocket first appeared in magazines. His artistic exploration introduced him to scientific and technological advancements, allowing him to be influenced by physics and astronomy.

The concept of the fourth dimension would play a pivotal role in shaping his artistic theories, pushing him to experiment with unconventional materials and provocative techniques. Fontana envisioned that art could go beyond its frame or surface, seeking to introduce spatial dimensions and create interaction between the canvas and its surrounding space. In 1947, Fontana, who was now in his 50s, founded the Spatialism art movement, fully promoting his innovative ideologies and departing from traditional artistic forms.

Exploring Dimensions Through Cuts and Canvas Manipulation

I do not want to make a painting; I want to open up space, create a new dimension, tie in the cosmos, as it endlessly expands beyond the confining plane of the picture.

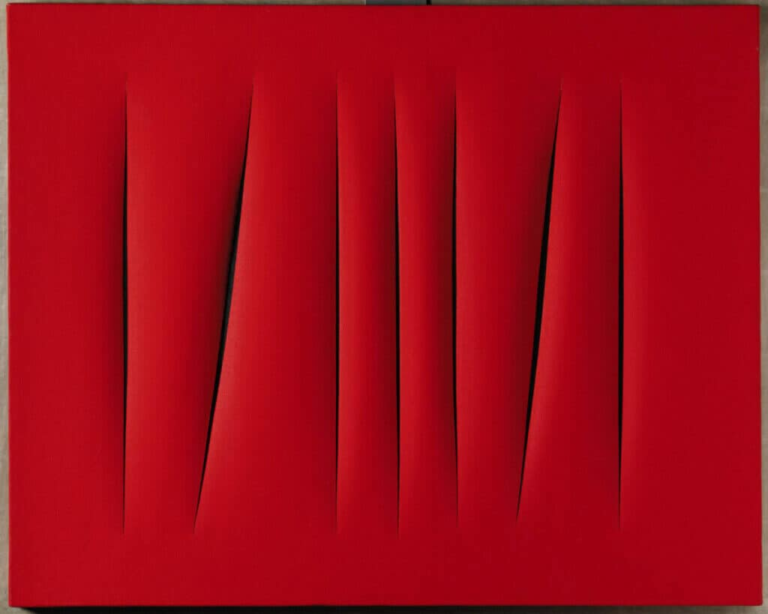

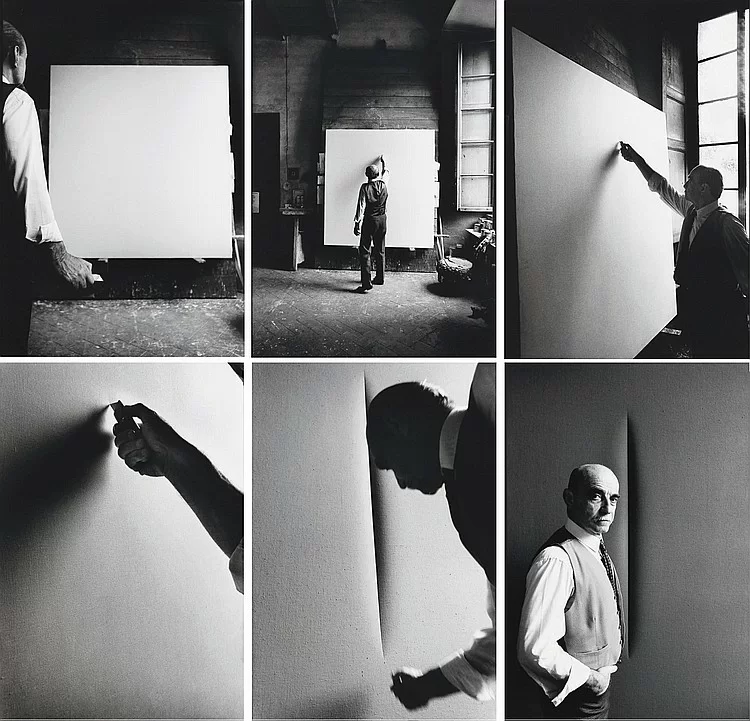

Leaving sculptures behind, Fontana focused on canvas-based art. Incorporating cuts, slashes, and perforations into his canvasses allowed Fontana to disrupt two-dimensional planes, giving his work a sense of depth. His deliberately placed cuts and slashes created dynamic and expressive compositions that have the power to engage its audience. The radical gestures created openings in the canvas that allowed viewers to unlock their curiosity and peer into the gaps, emphasizing the physical and conceptual exploration of space.

Fontana’s work demonstrates his ability to balance complexity and restraint and display intentional energy and movement through his artwork. Some of his works feature simple cuts and minimal interventions that emphasize the elegant simplicity of Spatial concepts. Other works, however, were more complex, impacting viewers and leaving them with a sense of tension and anticipation.

The 1960s marked the maturation of Fontana’s Spatialism movement. His international reputation grew, expanding not only in Europe but also in the United States and other parts of the world. Now in his 60s, Fontana was a leading figure in the avant-garde scene. It was also during this decade that he would produce some of his most celebrated and recognizable works.

The large dramatic slash across the canvas of Concetto spaziale, Attese (Spatial Concept, Waiting) (1960) makes it one of Fontana’s most iconic works as it exemplifies the artist’s commitment to the exploration of space through canvas manipulation. In Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio (Spatial Concept, The End of God) (1964), a central cut alters the two-dimensional surface, giving the viewer a three-dimensional experience. To engage audiences on a physical and conceptual level, Fontana took a different approach with Concetto spaziale, Natura (Spatial Concept, Nature) (1960) — sculptures in terracotta and in bronze; rather than a striking slash, he created a complex interplay through the deliberate holes and incisions to bring the inert density of matter into action.

My discovery was the hole and that’s it. I am happy to go to the grave after such a discovery.

On September 7th, 1968, Fontana died at the age of 69 of a heart attack. He left a legacy, one that emphasizes innovation, experimentation, and intellectual engagement in art. Today, Fontana’s works can be found in over 100 museums worldwide, including prestigious institutions like Tate Modern in London, the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

“Lucio Fontana: Spatial Concept” at Sorol Art Museum in Gangwon Province will run through April 14th, 2024.