Unforgettable plundering of private families and national museums for their great art collections by the Nazi’s occurred from 1933 until the end of World War II, otherwise known as the Third Reich. The most famous pieces of art that were stolen when the Hitler’s army went on their rampage of destroying and stealing valuable European art included the likes of Michelangelo’s Madonna of Bruges, Johannes Vermeer’s The Astronomer, Edgar Degas’s Place de la Concorde, and Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I.

By the end of the war, hundreds of thousands of cultural objects had been amassed by the Nazis. Much of the plundered art which included religious treasures, paintings, books, and ceramics have been recovered over the years and returned to their rightful owners. However, many of these works have been presumed lost, sold, or were auctioned.

But why would art that was stolen be auctioned? And with the participation of well-known art dealers, no less? And how do the families of the rightful owners of these artworks reclaim art that now exists in private collections or museums?

Lawful Journey to the Rightful Owners

In 1949, over 60,000 art objects that were confiscated from France during the German occupation were recovered; 45,000 of which were returned to their owners. However, more than 2,000 artworks would be considered orphaned and distributed to 57 French Museums. And since 1951, barely 100 have been reunited with the ancestors of the rightful owners.

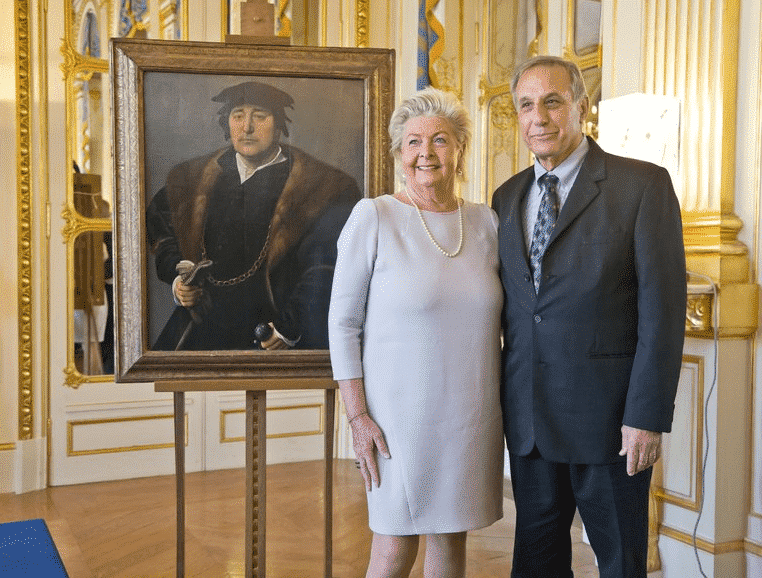

One of those works of art was a 16th-century portrait that would not be returned to the grandchildren of the rightful owner until 2016, more than 7 decades since German-Jewish couple, Hertha and Henry Bromberg, were forced to sell the work of art in Paris when they fled Nazi Germany.

The Commission and Foundation for Art Recovery

Critics insist that governments like that of France’s have not been proactive enough in seeking out the rightful owners of the looted art and reunite them with their descendants. And with privates sales and public auctions taking place in Switzerland in the many decades that have passed since Nazi Germany, the Commission for Art Recovery has characterized Switzerland as “a magnet” for assets from the Third Reich.

In 2013, France had pledged to track down the original owners of recovered artworks that were stolen during the Nazi occupation and yet, there is little evidence that there’s been much progress. No new funds have been dedicated to the project nor have any additional staff members been hired to speed up the recovery effort.

France’s culture minister, Aurélie Filippetti, argues that without inheritors or relatives to file formal requests that will trigger research procedures, they have very little to go on considering looted art is very difficult to identify.

Other European countries such as Austria have been taking steps to compensate Nazi persecution victims. Looted artwork that was auctioned in 1996 amounted to $14.6 million in proceeds and would be given to Jewish organizations.

And in 1998, Austria would become one of the 44 countries who would sign the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, a non-binding agreement to pursue just and fair solutions in restitution cases.

In 2015, the German Lost Art Foundation was formed by the federal and state governments in Germany to locate and identify cultural artifacts seized by the Nazi regime. For the first time, a financed plan has been put in place to track down artworks and seek who they rightfully belong to.

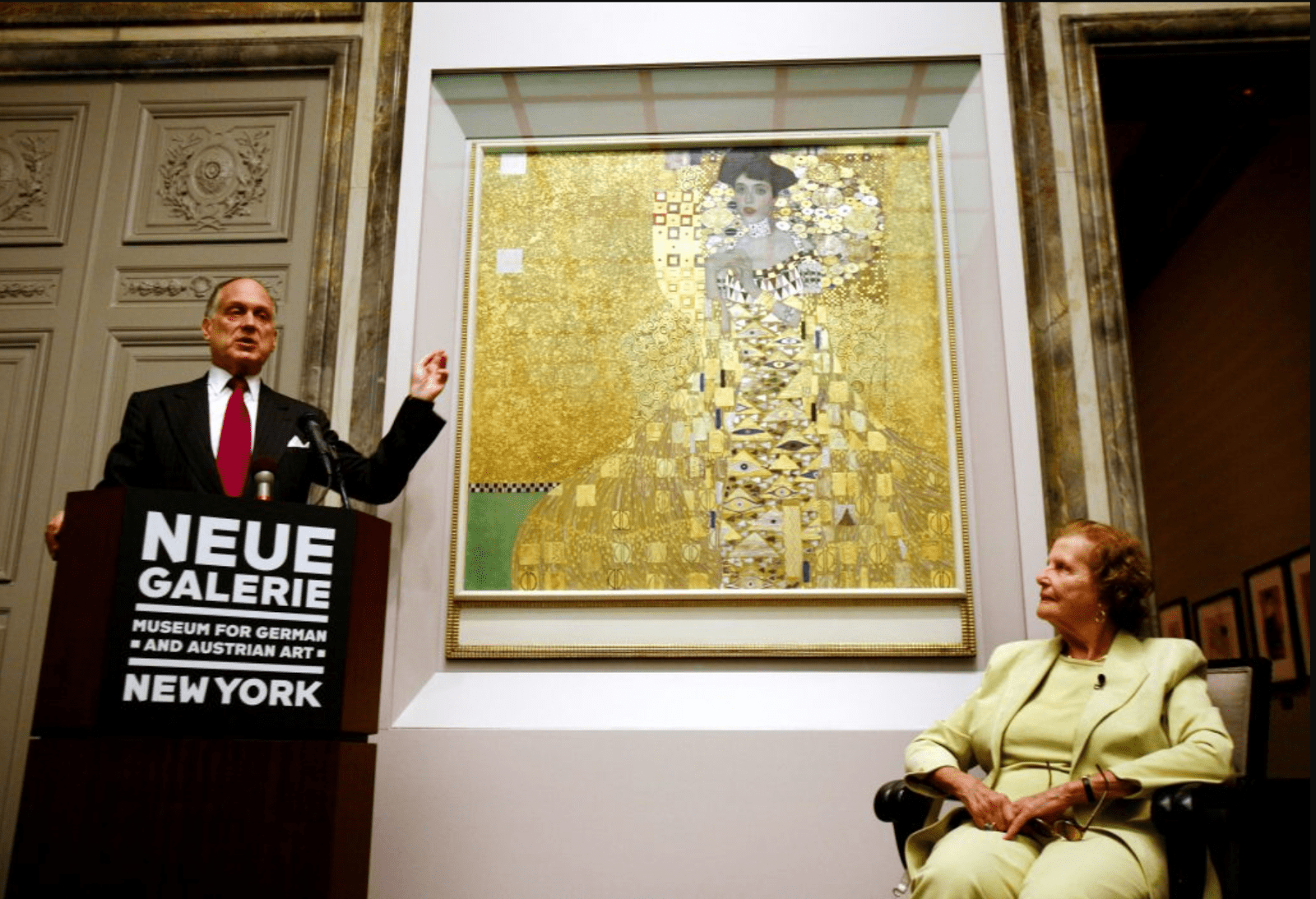

Legal Battle for The Woman In Gold

Today, much of Nazi-looted art remains in museums. For one, the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan (MoMA) holds the Adele Bloch-Bauer portrait and three paintings by German artist George Grosz. In fact, the heirs of Grosz filed a restitution lawsuit but lost the legal battle due to the statute of limitations invalidating their claim.

The Adele Bloch-Bauer portrait had its own international legal battle. Despite discovered documents indicating that Adele’s husband, Ferdinand, had been the rightful owner of the portrait when the Nazis seized it in 1938, Maria Altmann, the niece of Adele Bloch-Bauer, would invoke the Foreign Sovereignty Immunities Act. In 2004, the Supreme Court would rule in Altmann’s favor.

The UNESCO convention is pressuring institutions to be more rigorous with identifying the origins of artwork suspected to be looted. However, the struggle doesn’t seem to lie in the lack of manpower to carry out the research to reunite stolen artwork with the rightful owner or their descendants; the battle exists within laws, loopholes, statutes of limitations…and art institutions who must decide between ethical practices or the expansion of their collections.

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)