“All authentic art is conceived at a sacred moment and nourished in a blessed hour; an inner impulse creates it, often without the artist being aware of it.” – Caspar David Friedrich

A movement centered on individualism and nature, Romanticism sparked an intense interest in the emotions of fear, horror, and awe. One of the most celebrated artists of this era is Caspar David Friedrich. A German painter and draughtsman during his lifetime whose easily recognizable works were thought to have transformed the face of landscape paintings. As an artist keen on demonstrating his devotion to God through his work, he became a key figure of the Romantic Movement. His expansive, emblematic landscapes featured religious perspectives that attempted to create a spiritual connection. While his oil and watercolor works involved silhouetted figures, it was the vast, dramatic landscapes that drew the eye — reminding the viewer that our frail human presence made us inconsequential amidst God’s natural realm.

Revering the Romantic Authority of the Divine and Nature

Born on September 5th, 1774, Friedrich was the sixth of ten children of a soap-boiler and candle-maker. He grew up in Greifswald, a harbor town in Swedish Pomerania, which is Germany today. At the young age of seven, Friedrich experienced the fragility of life after witnessing the deaths of his mother and sisters. And at only 13, he lost his favorite brother, Johann, who had drowned trying to rescue Friedrich when he fell through the ice. It was perhaps these impactful losses that influenced Friedrich’s reverence of the divine and recognition of nature’s power.

Friedrich lived and studied in Copenhagen, where he studied at the University of Greifswald. At 24, he moved to Dresden, where his work would attract an admiring audience. In 1805, Friedrich won an art competition in Weimer organized by German poet, playwright, and novelist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe — entering two sepia drawings that von Goethe would describe as “ingenious” and “worthy of praise.” By 1810, Friedrich’s had won the favor of Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig of Prussia when Friedrich’s work was exhibited at the Berlin Academy. The Prussian prince bought Friedrich’s The Monk by the Sea (1808-10) and Abbey in an Oak Forest (1809-10).

The Monk by the Sea depicts a monk standing at the shore, looking out into the dark blue sea. The sky above portrays a clear, calm blue that hazily transitions into bluish-grey clouds, suggesting the threat of an approaching turbulent storm. What was most intriguing about the piece was its deliberate departure from conventional techniques as it willfully drew the eyes away from the picture rather than towards it.

Abbey in an Oak Forest is often referred to as The Monk by the Sea’s companion piece. The oil on canvas depicts a gloomy, misty graveyard through its use of blacks, greys, and browns. An eerie, seemingly deteriorated abbey looks over sunken tombstones and crosses. Surrounding it are bare oaks against a contrasting veil of the pale yellow of dusk.

The Shift from Stability to Solitary

However, the relationship with Prussian royalty soon soured after Friedrich began to express his liberal political views. Friedrich would then choose to distance himself by applying for Saxon citizenship in 1816. Thanks to Friedrich’s election to the Dresden Academy and a stable salary, he afforded his marriage to Caroline Bommer in 1818. His wife would be depicted in his paintings, and his works began to shift from lonesome figures to works featuring companionship. Unfortunately, Friedrich suffered an emotional blow in 1820 when his dear friend Gerhard von Kügelgen was murdered by a thief, triggering a period of severe depression. Living as an eccentric recluse, Friedrich’s friends would refer to him as “the most solitary of the solitary.”

In the decade that followed, Friedrich began to obsess over death and the afterlife, themes that took shape in this work. The artist began to lose patrons who were put off by the somber depictions of human mortality. In 1935, Friedrich suffered his first stroke, which resulted in minor limb paralysis. His reduced strength impacted his oil painting abilities, limiting him to rework his older pieces. Despite the diminished dexterity, Friedrich managed to produce an assumed final oil painting. The nocturne Seashore in Moonlight (circa 1835-1836) shows fishing boats at varying distances. The bright reflection of the moon glints to show the contrast of rolling clouds and rocky shore.

By the time Friedrich died on May 7th, 1840, following a second stroke, he had disengaged from public life, and his family was in a state of poverty. At some point, he’d even accused his wife of infidelity. His passing went relatively unnoticed by the art community.

The Waxing and Waning of Friedrich’s Legacy

One of Friedrich’s most celebrated yet controversial pieces includes The Cross in the Mountains (1808). The oil painting was designed to serve as a Christian altarpiece for the Tetschen Altar, the first time in art history that a landscape would be used to grace an altar. The gilded frame was also designed by Friedrich in collaboration with sculptor Christian Gottlieb Kuhn. The painting sparked debate for breaking landscape conventions and the use of unrealistic light, with viewers questioning the mystical illumination that gleamed from behind the mountain and fir trees.

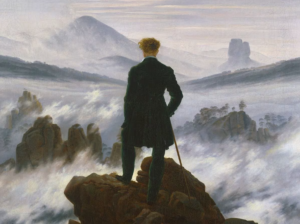

Art historians have analyzed Friedrich’s Wanderer above a Sea of Fog (1818) as one of the pieces hinting at a political statement. The “wanderer” at the center of the canvas stands calmly on jagged rocks facing a tumultuous sea. He stands seemingly unbothered, wearing what appears to be clothes often worn by those participating in Germany’s Wars of Liberation. Perhaps, the wanderer stands unwavering against the turbulent ocean and wind as he would when facing the government. The image has become iconic, evoking mixed emotions of peace, defiance, melancholy, and courage.

In Chalk Cliffs on Rugen (1818), Friedrich presents his audience with yet another mystery. Apart from being an antithesis of his earlier work with its bright, daylight theme, the painting depicts three figures. The woman clad in bright red is assumed to be Friedrich’s wife, whom he’d recently married. With her are two men, one wearing a tricorn hat with arms folded, and he stares out to the sea — almost as if he doesn’t notice he’s in anyone’s company. Beyond the reasoning behind the three characters, the year the painting was created also has been questioned — particularly after a watercolor and pencil paper version of the oil painting was created eight years after the artwork was dated.

Despite a reputation that steadily declined in the decade preceding his death, Friedrich’s body of work was not to be ignored and positioned him as an iconic figure of Romanticism. Unfortunately, this also meant gaining the attraction of the Nazi party, which attempted to promote their ideology through Friedrich’s work. Cursed as Adolf Hitler’s favorite artist, Friedrich’s legacy suffered.

However, over the decades that followed, his allegorical landscapes would be revisited and rediscovered — recognizing Friedrich as a visionary in the realm of Romantic landscape and icon. The art department at the University of Greifswald, from which he graduated, is now called the Caspar David Friedrich Institute. And he, despite fading into obscurity at the twilight of his life, would ultimately influence artists like Johan Christian Dahl, Mark Rothko, Arnold Böcklin, and Gerhard Richter.

“The artist should not only paint what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him.”

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)