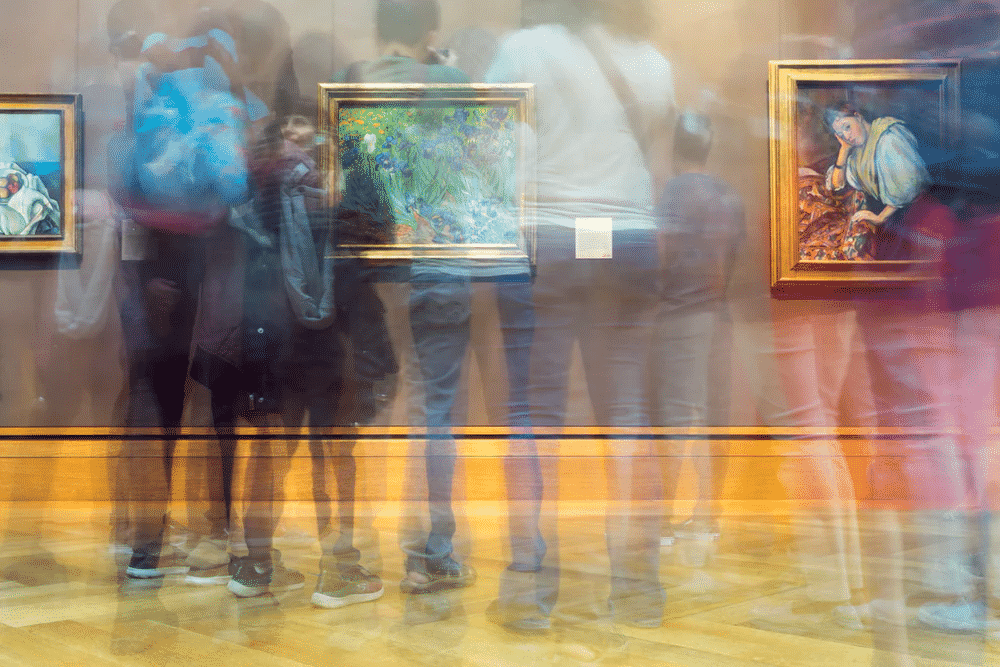

The common understanding is that museums are a place of cultural and historical importance where philanthropic ideas of curatorship, education, and conservation are preserved and encouraged for the benefits of greater public. But increasingly, museums are also being used as a tool to serve the agenda of their super-wealthy patrons, their board members. It would stand to reason that this situation will only create a conflict, as in the recent case of Warren Kanders, the vice chairman of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Kanders’ company manufactures military and law enforcement supplies including tear-gas grenades that had been used against migrants in US-Mexico borders and other protest sites.

Kanders kept his board seat for over seven more months until a group of more than half a dozen artists pulled their work from the 2019 Whitney Biennial. He then finally decided to resign, saying that his presence will only undermine the museum. In his letter of resignation, Kanders did mention that a “politicized and oftentimes toxic environment had put the work of the [Whitney Museum] board in great jeopardy” based on an “insidious agenda.” Kanders blamed the artist protesters with a politically motivated agenda and victimized himself for the displacement from his privileged museum board position.

To better understand the situation, we must demystify the inner workings and secrets of the art world. And understand how the systems of the art industry, from galleries and private dealers (who are often gallery owners), auction houses and art fairs, and even private collectors all impact the system of art business as a machinery in whole.

The way things are supposed to work is that private collectors collect their desired art while museums look to attract art collectors as patrons of their institutions supporting the museums and ensuring their welfare. By putting together a list of eminent collections and by attracting like-minded collector-patrons, museums are able to improve their programs through donations, be it in the form of money or private collectors’ prized art collections in order to strengthen the museum’s tradition and legacy. The reality, however, is not as straightforward.

US museums are primarily dependent on private philanthropy. To entice important collectors and philanthropists, museums often offer them a seat on their boards. The board is where all the major decisions are made, overseeing acquisitions, and influencing important programming decisions. The board can also hire and fire museum directors or other top leadership positions. Therefore, having a seat on the board is a major competitive advantage, particularly when it comes to the influences it plays on living artists’ works when they are the favorites from board member’s own private collections. When a major museum starts collecting the works of a particular artist, their prices and overall value will also rise significantly, and consequently elevating the value of the collection of the board member too. What’s more, board members have priority when it comes to buying those very artworks as influential VIP collectors to the top private dealers and galleries.

The Role Of Art Biennales For Artists

Biennales are international events that showcase contemporary art every two years. Today, there are over 100 such biennales across the world, from Venice to Istanbul, Berlin, Moscow, SãoPaulo and Sydney to Shanghai. All of them are competing with each other for the attention of major curators and private collectors and institutions, thus attracting cultural capital, revenue, and a boom in local art tourism.

“Biennials and large group exhibitions represent the opportunity for an artist to develop and present work in the context of many colleagues from various places around the globe. And I strongly believe that the dialogues that these encounters potentially promote are what really matter,” said Jochen Volz, curator of the São Paulo Biennial.

Klaus Biesenbach, co-founder of the Berlin Biennale and director of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, shared his thoughts on the importance of biennale exhibitions, “These large shows also are the occasions for which new relevant work is produced and seen in relation to and at the same time with other relevant artwork. And these big shows have the critical mass and public visibility of making contemporary art present as a challenge and as a statement. They even suggest art still has a disruptive relevance in our society.” He went on to say that “Going to an art fair is nothing in comparison to going to a curated exhibition where organizers and artists really cared for the form and the content of the exhibition, not its sell-ability and or the fact if visitors can take small or medium-sized colorful pieces home and place them behind their couches and hope they quintuple their value in two years.”

In an interview for Artspace, former investment banker and Brussels-based collector Alain Servais got real about the process of high-stake exhibitions and biennales, saying, “Right now only the wealthy galleries can get their artists work into museums because one of the problems is: who can produce the works? Who can put the money upfront for massive pieces for exhibitions and biennales? With the multiplication of biennales it’s endless, and you need really deep pockets to be able to do it. You also need deep pockets because you won’t make any money out of the piece that you’re going to be producing.” He continued on his dissatisfaction with the current art industry “With Gucci or Prada, they don’t sell the catwalk pieces, they sell more standard products in the shops, and it is there they make money. With art it’s the same. That means you’re producing a work in the gallery that hardly anyone will be able to buy.” In other words, the art world is now, in a way, acting just like the fashion industry.

However, the impact and influence of major biennials on artists’ careers cannot be underestimated. For instance, during the 1964 Venice Biennale, the US Pavilion, together with Leo Castelli, a legendary New York art dealer organized a supplemental show that introduced the arrival of Pop Art on the international stage. It was also at that time when the art world’s gaze moved from Europe to the United States. Claes Oldenburg, Jasper Johns, Jim Dine, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Rauschenberg were among the attending names, with Rauschenberg even winning unexpected Golden Lion, the Grand Prize that ensued the backlash — sparking great debate among the European elite at the time.

Recently in 2019, representing US at the Venice Biennale, African-American artist Martin Puryear made it in the spotlight with his powerful sculptures in different medium highlighting poignant themes of slavery and ideal of liberty and freedom.. For Puryear, an American artist who was relatively unknown to the international art crowd in spite of his 2007 solo show at MoMA, it was a crowning occasion for a 79 year-old artist to be finally acknowledged as a world-class artist that will undoubtedly bring critical re-evaluation and financial rewards.

Still, Everything Is for Sale

The Venice Biennale, the largest and most prestigious among these events, lasts for six months with special installations and exhibitions spread all across the historic city. For those in official positions, the event needs to be free of any commercial interests and profiteering endeavors. “We must not fall into the trap of letting ourselves be guided by the market,” said Paolo Baratta, the Venice Biennale’s president in 2019. The event should not be suspected of “compliance with selling strategies,” he went on to emphasize.

Unfortunately, however, many high-flying art collectors have been looking at these biennale shows as if they were art fairs. They don’t necessarily feel constrained by the idea of a commerce-free environment and have begun buying art after the biennial has concluded or make offers while they’re visiting biennale exhibitions. Those art dealers who represent participating artists in the biennales eagerly take part in this process, spending huge amounts of money catering for their clients with custom-themed VIP events and parties.

At the international group exhibition of the 2019 Venice Biennale, those works displayed in particular groupings resembled more like commercial gallery exhibitions than anything else. During the 2015 Venice Biennale, French mega collector François Pinault went on a spending spree of $8.9 million and purchased a series of large-scale paintings by Georg Baselitz, a German artist which was exhibited at the Arsenale building

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/artist-and-art-dealers-discussing-paintings-digital-tablet-558270525-5c317008c9e77c00014fdf32.jpg)

How Do Galleries Fit in the Art Market’s Informal Economy?

The term “informal economy,” or more commonly known as the gray market, refers to any transactions that go unrecorded, untaxed, or are unregulated. Even though this sounds pretty similar to the black market, the difference between the two is that the so-called informal economy is not strictly illegal. And when it comes to the art industry, many financial matters fall within this informal economy, if not even bordering on the illegal.

Take, for instance, the role art galleries play in determining the price of artworks. Granted, no market in the world is truly free; the price for any given commodity is set by the principle of supply and demand. This price is also publicly known, and the commodity will eventually find its way to the highest bidder. This is not the case in the art industry, however. Here, art galleries will keep their sales prices private and will even go as far as choosing which private collections will get the piece of art. This is the so-called “primary market” as in the art market term. Art galleries typically want to work with their preferred art collectors that will not turn around and sell those works at an auction house or namely the secondary market too soon. Once here, the artwork price becomes public, and anyone is essentially free to make a purchase.

The fact of the matter is that the majority of primary art sales—meaning art bought directly from the artist—happens through the gallery system. Just like museum board members who are art collectors, gallery owners have a vested financial interest in setting the prices and controlling and manipulating the market. Yet, if we were to ask them why they do this, most will say that it’s in the artists’ best interest. And interestingly enough, there is some degree of truth to that statement.

Given the highly subjective nature of taste and connoisseurship in art, resulting in the arbitrary pricing practices and opaque inner workings of the art industry, setting a clear price on art based on limited available information is next to impossible. As such, the art market has found a way to regulate itself by having a handful of influential museums, high-end galleries, dealers, and collectors determining the value and, by extension, the price of any given artwork in the art market. Therefore, art dealers and gallerists will invest plenty of resources in building and promoting their hand-selected artists’ brands and their bankability. Approved by a few top galleries, collectors, and museums and their manufactured brands of preferred artists groups are the new currency of the contemporary art world.

They do need to be on guard and take carefully calculated risks because the worst thing an art gallery can do is to overprice an artwork. Seasoned and well-educated art collectors won’t likely overpay, and galleries can’t lower the price if the series of invested works don’t sell. Doing so will only stand to hurt the value of the artist’s works but also their own reputation and credibility of the gallery itself. Therefore, art dealers would be more inclined to drop an artist than to lower the price of their work.

High Quantity Leads to Low Quality. In the Art World, It Also Leads to Higher Prices.

Several decades ago, the art industry was a fairly niche trade, centered mostly around Western Europe and the United States. Today, most of the world, from Latin America, China and Asia, to the Middle East and Africa, is embroiled in it. What’s more, the art market has turned into a multi-billion dollar global juggernaut wrapped around the fashion, luxury, and celebrity culture, and lifestyle industries. It has since attracted the attention of the ultra-wealthy buyers who are now competing with each other over an haughty pursuit of hot commodities game in contemporary art-collecting and investing their wealth in so-called “blue-chip” brand-name artists.

Thomas Seydoux, the former chairman of Impressionist and Modern art at Christie’s, recalls that “When I started out, 30 years ago, millionaires had boats and jets—but didn’t necessarily have any art at all. For the very wealthy today, it’s not fine not to be interested in art.”

In her book entitled Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Market in the Twenty-First Century, Georgina Adam, a contributor to the Financial Times and an editor-at-large for Art Newspaper, also takes into account the negative effects of this phenomenon. With a large and somewhat sudden influx of money being pumped into the market, contemporary art is increasingly seen as more of an asset class to wealth portfolio. Art to the new opportunistic collectors is no longer prized as much for its meaningful aesthetic value and fundamental qualities, as it is more similar to bonds, equities, and real estate. In turn, this trend has pushed some artworks to become vehicles of hiding or laundering money, as well as encourage artists to create sub-standard quality works so as to favor speed and quantity.

It’s also no coincidence that some of the most prominent art collectors today include the Sackler family, Alice Walton (Walmart heiress), as well as Poju Zabludowicz and Daniel Och. Zabludowicz was involved in a controversial bribery scandal with Benjamin Netanyahu in 2017 and his family fortune was built on arms dealing. While Daniel Och’s firm paid millions in bribes to African government officials in exchange to benefiting from mining rights. It’s no wonder they would much rather be known as philanthropists and art patrons than for their other activities.

How Can Emerging Artists Make It in This Environment?

Knowing the secrets of the art world can be discouraging. Based on such an unregulated, secretive, and highly manipulated art market, it would seem next to impossible for emerging artists to become successful and secure a successful art career and legacy. However, knowing more about the gallery system, biennales, and art fairs, and auction houses can be empowering and help guide you through your art career and monetize your creative passion and artistic endeavors.

As an up-and-coming emerging artist, you need to learn how to take in charge and promote and sell your work. Luckily, this is not nearly as difficult today as it once was. Like with any business decision, everything needs to start with a clear and focused goal in mind. Be it more exposure, more sales, or the opportunity to network and exhibit artwork in gallery shows and art fairs; you will need to determine what you really want in your art career. This decision will influence all of your steps going forward and help set your targets that need to be accomplished.

The second step of the process is to build your art portfolio. This is essential to preserve your art throughout all stages of your artistic development in order to build your personal brand, as an artist as well as to promote your work professionally. Having all your work in one place will make it much easier to update your status on your website, submit it to competitions, apply for residency programs and grants, as well as to attract the attention of collectors, art dealers and galleries and represent your work in art fairs. Don’t forget to also include your bio, your artist statement, and contact information. You need to make it as easy as possible for potential customers or interested gallerists and curators to find you.

Maybe you lack confidence to network and expand your horizon, but however challenging it can be, having a comprehensive network of connections in the art industry will make it that much easier for you to advance in your career. It will also help you grow personally and professionally, giving your art career the support and boost it needs. Make sure to start reaching out in online or in-person meet-ups and professional gatherings and attend all types of available art organizations and community events, art fairs, street shows, and various charities. These networking activities will provide you with much-needed exposure and engagement with your peer artists and art professionals. Just don’t forget to follow up on these contacts to build and maintain valuable relationships over the long-term to create a life-time network to support your career.

Getting Endorsed by an Art Gallery

When you have very limited exhibition exposure and experience, few sales, and no real notoriety (Banksy for example), it’s pretty hard to get endorsed by an art gallery. Many feel tempted to send out as many cold-calling emails filled with art image attachments to as many galleries or dealers that they can find. Their thinking is that there may be an off chance that one of them will reply back and provide their patronage. Unfortunately, this is never the case, and almost no gallery will respond to unsolicited emails or unexpected visits. But there are some steps that you can employ in order to increase your chances at a gallery representation.

You will need to start by doing some in-depth research on the galleries you want to work with by reviewing their exhibition list and finding out their frequent curatorial themes and directions. Just like you in your own art making processes and methods, these establishments have their own creative visions in their artists’ portfolios. They will not endorse just anyone if those visions are not quite aligned. Take some time to decide whether you would make a good fit for each other before you consider contacting them. Once you’ve identified one such gallery, look to building some rapport and relationship with them. Start by subscribing to their mailing list, interact with them on social media, and attend their gallery openings and events. In other words, do your best to get on their radar and get noticed as an emerging artist by trying both online and offline.

It’s also a good idea to have an already established audience before coming in contact with a gallery. While it’s true that building an artist’s brand is among the duties of an art gallery, it’s always better to have a foundation of fans already in place. It also shows that you have some basic knowledge of how to market yourself and ready to promote your artwork. Finally, be prepared to talk about your work. Art enthusiasts, gallerists, and art dealers want to hear the artist speak about their work and what they’ve done. So, don’t just let your work “speak for itself” and, instead, take a more proactive and interactive approach to get noticed.

What Is the Future of the Art World?

In 2015 when Eli Broad, American businessman and philanthropist, opened his own contemporary art museum, The Broad, everyone was expecting to see the same thing as before —a world-class art collection housed behind a gilded facade of a museum with limited access to the public. Yet, what came out of the project was a hybrid of a storage site, like the Schaulager in Switzerland, but one that ensured that a collection would become shown and enjoyed by the public and art professionals. Basically, they made sure that their collections were allowed to circulate and be shown regularly through the foundation’s innovative art-lending program called “library” and keeping their philanthropic commitment to the public.

With ARTDEX, you will get the same thing like the Schaulager but in a digital sphere. We help artists and art collectors catalogue and archive their work starting from the beginning of your art career all the way to the present. We offer a complete and free digital archive and storage solution where all your work can be easily documented and preserved. Our mission is to showcase, celebrate, and promote all the works of the art world, not just those top-end artists’ works represented by the high-end galleries, but a massive emerging art community of undiscovered talents from every corner of the world. Moreover, ARTDEX also works as a professional network for art professionals and enthusiasts, allowing you to connect, network and share your digital inventories. The digital world has changed everything, and ARTDEX is in the lead, breaking down those age-old barriers that exist in the art world. We are here for our growing global community championing digital inclusion, accessibility, and true democracy to the world of art, for all.

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)