There’s a divide between artists; those who believe that a title helps give the artwork its identity, those that don’t give titles much thought, and those who deliberately do not title their work.

Why do artists leave their work untitled?

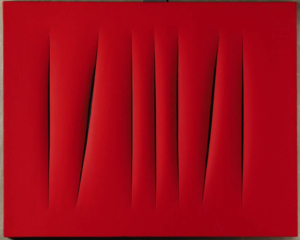

Many visual artists philosophize that their art should speak for itself and allow the viewer the freedom to develop their own interpretations. By intentionally omitting titles, the artist keeps the work’s meaning open-ended and the artwork transcends beyond the constraints of categorization and representation.

And before the founding of auction houses in the 18th century, plenty of artworks remained untitled and titling conventions became necessary for logistical purposes. With the growth of the auction market during the 19th century, the number and size of museums also expanded. As cataloguers and gallerists pushed artists to be more content-descriptive with their works, more artists decidedly skipped the practice to stand against institutional frameworks.

The ‘title or not to title’ debate

Artists today can continue to defy conventions and create art that spur open interpretations. However, choosing to leave artwork “untitled” has become so pervasive that it no longer evokes the same rebellious charm that it may have once had. Not giving your artwork a title has also become impractical – especially if you plan to make a living through the sales of your work.

In these modern times, artists have the power to control their narrative and branding. Online spaces allow you to engage and communicate with your fans and art audiences. Potential buyers, like most consumers today, turn to the internet to learn more about their purchases. And without titles to give your artwork context or serve as a form of introduction, you not only risk closing the conversation surrounding your art but make it challenging for potential collectors and art buyers to find you online. In this digital world, titles work like keywords, serving as descriptions while also increasing searchability. For artists, titles are your de facto ‘elevator pitch’ for when you’re not there to verbally describe your work. And in the same way that knowing someone’s name makes them feel less like a stranger, giving your artwork a title makes it more accessible.

But how do you come up with a compelling title for your artwork that will provoke engagement and capture the attention of potential art buyers? Here’s how.

Define your intention

Give your artwork a title that allows the viewer to focus on your intention. Because while an untitled work can be mysterious, it can become so open to interpretation that future generations quibble over its message. And your artwork may gain a title or nickname from viewers that you may not be happy about.

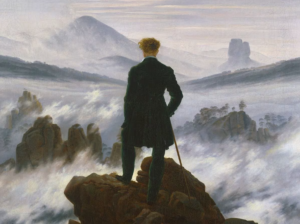

Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (1665) could have easily been titled Girl with an Oriental Turban, Girl Wearing an Exotic Dress, or Girl with an Enigmatic Expression. In fact, the painting has carried different titles throughout different countries and catalogs over the centuries. At its 1696 sale, it was described as “Portrait in Antique Costume, uncommonly artistic.” It did at some point become known as Girl with a Turban according to a 1675 inventory. And by 1995, it had the nickname Girl with a Pearl. It’s unclear if Vermeer had intended for the pearl earring to be the painting’s focal point. Because the painting lacked a title from the artist describing the mysterious girl’s identity or occupation, we may never know.

State the obvious

Giving your artwork a title doesn’t have to be complicated. A painting of a fire hydrant can be blatantly titled “fire hydrant.” A yellow circle can be “A Yellow Circle.” We saw how this titling concept worked for Mark Rothko with his Orange and Yellow (1956) and Black in Deep Red (1957). Stating the obvious works especially well for still life, allowing you to be deliberate yet descriptive.

Consider your audience

What do you want your audience to understand about your work? Is it the significance of the subject or the complexity of the process? We know that collectors who purchase art often explain their collections to fellow art enthusiasts. So, when you give your artwork a meaningful title, you give art buyers the opportunity to discuss their acquisition with more confidence.

Hide a secret

Titles can be random or deliberate. Your intentions don’t always have to be revealed. You don’t have to literally explain your choice of subject or medium. Make the title personal and meaningful, as if you’re sharing a secret with the artwork. It can be a pet name for your muse or the favorite snack that fueled you during the work’s creation.

Keep it short

If you want the art to do the talking, keep your titles short and succinct while avoiding cliches. If a phrase registers in your brain as a cliché, it most likely is. Cliches lack the power to evoke new emotional experiences; they’re also lazy. It’s better to be obscure and quirky than make your audience draw back with lack of original thought.

Get technical

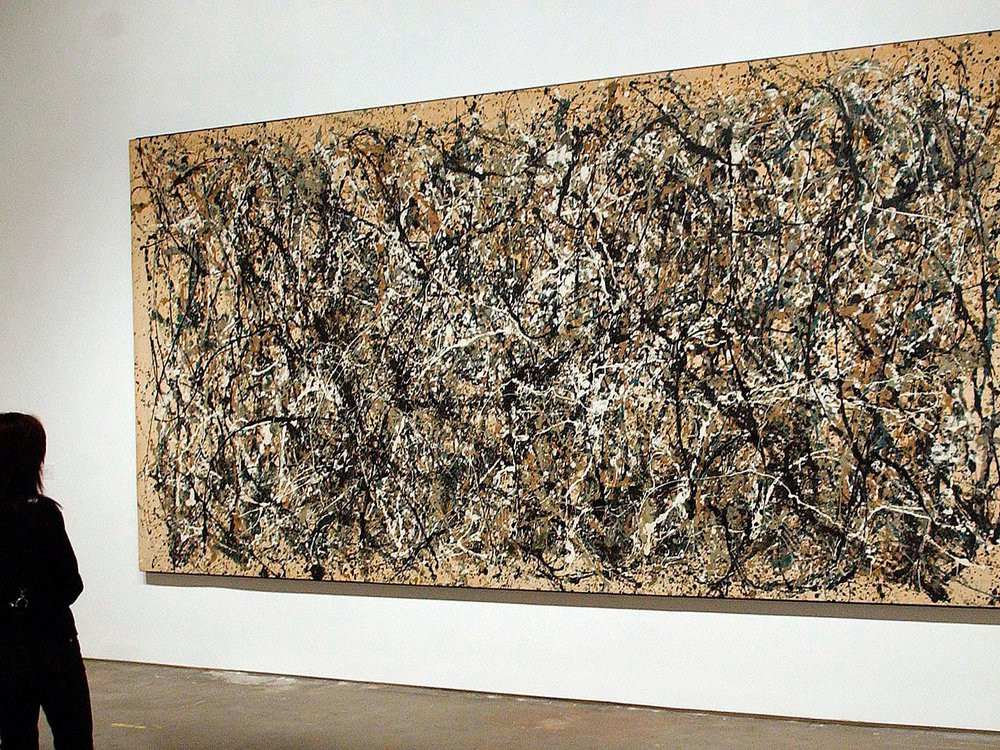

Titles don’t always have to be poetic, melodramatic, or emotionally charged. Titles can be a date, a time, a number, a medium, or location. The title can simply lessen confusion when cataloging, particularly when working with series. Jackson Pollock, like many artists, worked in a series. Pollock preferred to use numbers instead of words to title his paintings. Pollock’s wife, Lee Krasner, explained Pollock’s reasoning: “Numbers are neutral. They make people look at a painting for what it is—pure painting.”

Tell a story

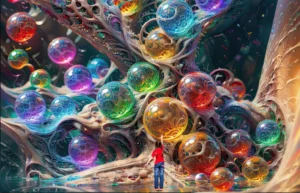

Whether it’s a landscape, abstract, or photography, approach naming your art as art itself — a narrative that connects to its visual composition. Adjectives and adverbs add dimension to both your title and the artwork’s visuals, inviting the viewer to take a closer look. The title may even allude to what’s happening beyond the visual.

Anyone who has navigated art spaces has encountered at least one Untitled work; perhaps millions or more exist in the art world, after all. The practice of negating any accompanying labels has become so common that viewers probably don’t pause to consider why. And it’s exactly this shoulder shrug that today’s artists should fear. In this content-rich world, viewers crave description. And leaving artwork untitled feels like a default setting when you have nothing better to offer.

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)