What Makes Art “Great”?

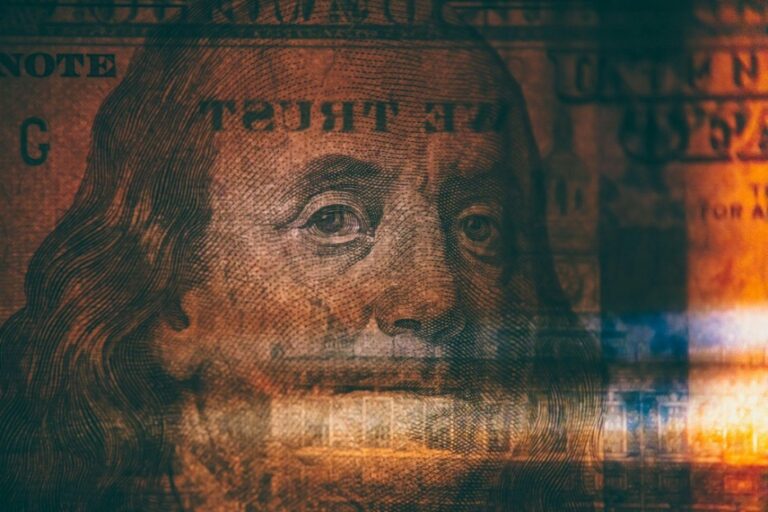

A Jean-Michel Basquiat painting sells for $120 million. Meanwhile, an equally striking canvas by a gifted but unknown artist collects dust in a modest studio. What separates these two pieces? Is it innovation, emotion, cultural relevance, or something more transactional?

The answer is increasingly clear: economics plays a defining role in shaping our perceptions of artistic greatness. Who pays for art, who promotes it, and where it’s seen has as much impact as what’s on the canvas itself. From Renaissance patronage to today’s speculative art funds, money has always been quietly curating the story of “great art.”

Let’s follow the money and unpack how the art world’s economy shapes not just what sells, but what survives.

From Patronage to Power Collectors: A Brief Economic History of Art

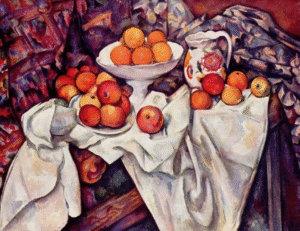

The link between wealth and artistic recognition is centuries old. During the Renaissance, the Medici family didn’t just commission art, they sculpted cultural narratives. Michelangelo and Botticelli weren’t just artists; they were brand ambassadors for Medici power. Art was a political and class currency, beyond mere social capital.

Fast forward to 18th-century France, where salons dictated taste and royal commissions signaled cultural superiority. In the Gilded Age, American tycoons like J.P. Morgan and Henry Clay Frick collected European masterpieces to assert social stature, essentially importing greatness by the crate.

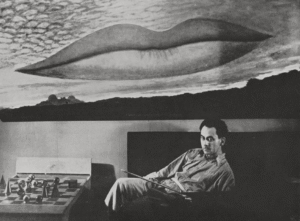

In the post-WWII era, Abstract Expressionism became America’s visual identity, aided by government initiatives and influential collectors, fueled by the McCarthy era American jingoism. Jackson Pollock’s rise wasn’t just artistic, it was strategic. He was the poster child of a capitalist culture war.

Timeline Highlights:

- 1400s: Medici sponsorship of the arts

- 1700s: French salons legitimize academic style

- 1900s: American collectors shape museums

- 1950s: U.S. uses art as Cold War propaganda

- 1980s–Now: Market forces dominate artistic value

Art as Asset Class: When Beauty Meets Investment

By the 1980s, the art world began to resemble Wall Street. Art became an asset class — one with high volatility, opaque pricing, and massive upside. The financialization of art took off, driven by speculation, scarcity, and savvy branding.

High-net-worth collectors started buying art the way hedge funds buy stocks. Offshore storage facilities like the Geneva Freeport house billions in art, untouched by light or public view — because the goal isn’t appreciation, it’s appreciation in value.

As Don Thompson, an economist and professor of business, notes in The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: the Curious Economics of Contemporary Art, fame, story, and exclusivity inflate prices. A Koons or Hirst work sells not only because it’s bold and shocking, but because the market says so — through limited editions, elite galleries, and targeted buzz.

Pyramid of Market Power:

- Base: Emerging artists trying to gain exposure

- Middle: Blue-chip galleries controlling visibility

- Top: Auction houses, mega-dealers, and museums that define “worth”

The Role of Gatekeepers: Galleries, Auction Houses, and Fairs

Art doesn’t sell itself. Behind every million-dollar sale is a network of gatekeepers. Blue-chip galleries (like Gagosian, David Zwirner, Hauser & Wirth, or Pace) decide who gets shown. Their backing often determines whether an artist becomes collectable, or invisible.

Auction houses amplify this influence. Sotheby’s and Christie’s not only sell art — they build narratives around it. A record-breaking sale fuels hype, drawing collectors, media, and museums into a self-reinforcing loop.

Art fairs like Frieze and Art Basel further consolidate power, creating exclusive spaces where access often depends on who you know. These events function less as exhibitions and more as cultural stock exchanges.

The Loop:

Gallery representation → Art fair exposure → Museum acquisition → Auction spike → Collector demand

Museums and Market Symbiosis: Who Validates Whom?

Museums are seen as neutral arbiters of quality, but their decisions are often economically influenced. Donors and board members—many of whom are major collectors—help determine what enters the institution’s collection.

When a museum acquires a piece, its market value surges. This acquisition, in turn, raises the prestige of both the artist and the collector. It’s a symbiotic relationship: museums confer legitimacy, while collectors provide funding and artworks.

Case in Point:

Yayoi Kusama’s transition from niche figure to global icon wasn’t accidental. A series of retrospectives and gallery promotions turned her into an art market juggernaut. Her installations now sell out worldwide, and her stratospheric auction prices reflect that.

The Invisible Artists: What the Market Ignores

In 2024, René Magritte led global fine art auctions, with his works generating a staggering $312 million USD in sales. He was followed by Claude Monet at $293 million and Pablo Picasso at $222 million, underscoring the enduring dominance of male, Western artists in the highest tiers of the art market.

But what about the artists who never receive that kind of exposure?

For every blue-chip name commanding millions at auction, there are thousands of brilliant creators who remain invisible — overlooked due to race, gender, geography, or lack of market access. Swedish artist Hilma af Klint, for example, was creating spiritual abstractions years before Kandinsky, yet her work remained largely unknown until the 21st century. Why? Because she didn’t fit the dominant narrative — one centered around male, Western modernism.

This exclusion isn’t just about visibility, it’s about value. In Talking Prices, art sociologist Olav Velthuis explains that pricing in the art world is not purely economic; it’s symbolic. It signals legitimacy, status, and inclusion. So when certain artists are consistently left out of the market, they’re not just underpaid — they’re often erased from the historical record.

A 2024 study of the top 10 contemporary artists by auction sales (July 2023–June 2024) revealed that nine out of ten were men, spotlighting a persistent gender imbalance at the upper end of the art world.

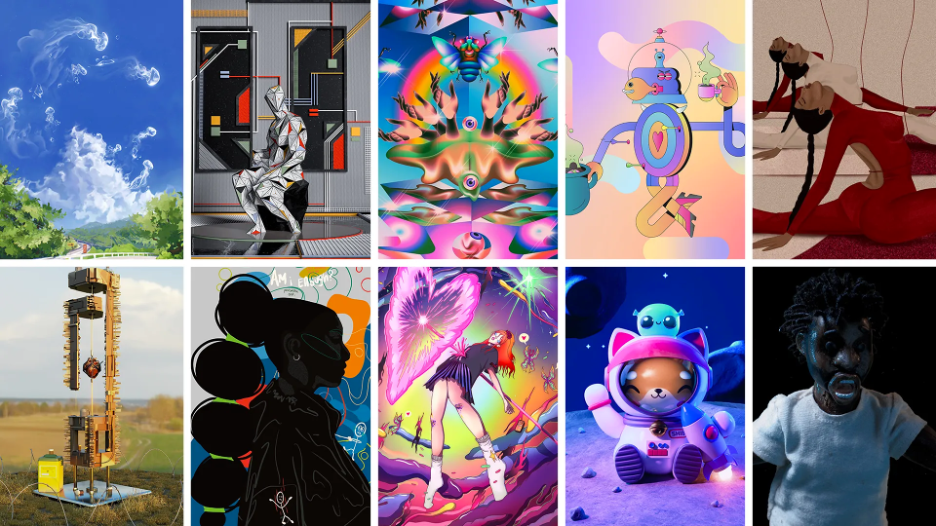

New Frontiers: NFTs, Digital Art, and the Democratization Myth

NFTs promised to bypass traditional gatekeepers. Digital creators suddenly had access to global collectors, with blockchain ensuring authenticity and direct compensation.

Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days sold for $69 million in 2021, marking a seismic shift. Yet even in this “open” market, new hierarchies formed. Crypto elites replaced gallerists, platforms curated who got visibility, and hype often outweighed substance.

An art critic and professor of art history, Claire Bishop’s essay “Digital Divide” critiques how institutional biases persist even in supposedly democratized spaces. The decentralization of art distribution doesn’t automatically mean decentralization of power.

NFTs: A Double-Edged Sword

- Pros: Transparent ownership, global access, direct artist revenue

- Cons: High speculation, short-term market cycles, replication of old power dynamics

How Should Emerging Artists Navigate This Landscape?

So, what’s an emerging artist to do in this dizzying ecosystem?

Success today requires more than talent; it requires strategy. Artists must understand market dynamics without letting them define their vision. A sustainable career is built not on viral moments but on community, consistency, and connection.

Artist Survival Guide:

- Build real relationships with peers, curators, and audiences

- Choose representation thoughtfully, not all exposure is good exposure

- Participate in alternate economies like residencies, collectives, and mutual aid networks

- Understand your pricing as part of your story, not just a number

- Define success on your own terms

Conclusion: Greatness Isn’t Just Made, It’s Marketed

Artistic greatness is not purely meritocratic. It’s constructed through a web of economic interests, institutional endorsements, and strategic positioning. By following the money, we unearth the invisible forces shaping what the world sees, and what it forgets.

This isn’t a call to cynicism. Rather, it’s an invitation to awareness. When we understand how narratives are built, we can start to build better ones — ones that reflect a broader, richer spectrum of human creativity.