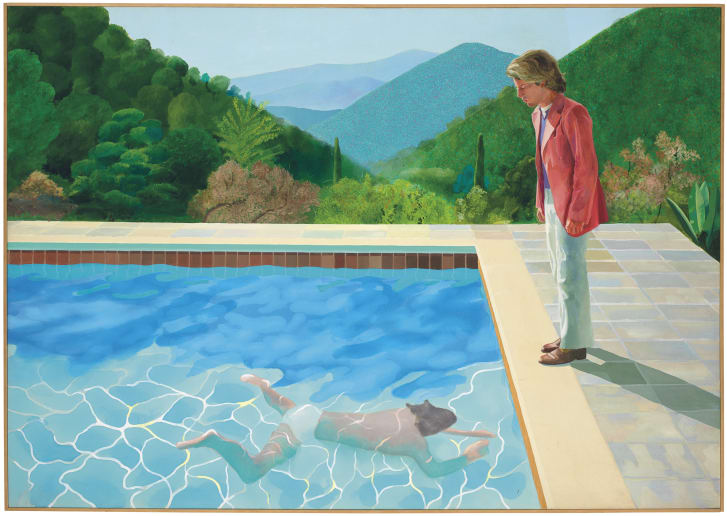

“I always loved swimming pools, all the wiggly lines they make,” said David Hockney, the author of a painting “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)” that set the record for a work by a living artist sold atauction. “If you photograph them (swimming pools), it freezes them whereas if you use paint, you can have wiggly lines that wiggle.” Those wiggly lines Hockney froze with his brush were eventually paid $90.3 million at Christie’s auction house in New York on November 15.

Ninety million for a painting by an artist who is still alive and is walking among us? Seems unbelievable, but it’s not like this was a total surprise for the people in the art world. Hockney is one of the world’s most famous artists, whose last retrospective, hosted by Tate Britain, had over a million visitors. So maybe one of those million fans was ready to cash out such an enormous amount of money. Perhaps the unidentified patron loved the painting surely, beyond doubt. Or maybe not. If you start thinking about it, it becomes a real mystery. For ordinary art lovers like us, we wonder – who is capable of paying so much for a piece of art, and for all the world’s art sake, why would anybody?

Why Do Collectors Spend These Crazy Sums on Art?

The answer to this question might be found in the Nathaniel Kahn’s recently released documentary film “The Price of Everything.” Kahn illustrates that it all changed in 1973 when a New York taxi tycoon Robert C. Scull, a passionate collector of Abstract Expressionist and Pop Art, put his collection of modern art on auction. Works that he bought directly from the authors sold at prices up to fifty times higher than what he paid. One of the artists whose painting was sold at the auction, Robert Rauschenberg, was particularly unhappy with the situation because he felt like he was scammed. In reality, there was no fraud. Everything was clean and legal. Scull understood that the artistic value of the paintings he obtained had risen, so he wanted to sell them for a more significant price and make a profit.

Ever since then, rich people are looking to buy unique paintings and sculptures, not because of the appreciation of art, but because they see it as a good investment. Stefan Edlis, a philanthropist from Chicago, explained the whole situation this way: “There’s a lot of money kicking around, and there is a limit to where you can put it. To be an effective collector, deep down you have to be shallow… You want to think that you work with rugs, to work with furniture.”

What this means is that these wealthy businessmen and women sniff around, trying to understand which pieces have the most substantial value. Then, they buy them hoping that one day those same pieces can be sold at a much higher price than they had paid, while they enjoy at their shiny trophy homes and corporate offices. But how to figure out the most profitable work of art, and how do they find them?

Like in Every Business, There Are Always Trustworthy Dealers

Big time art collectors and investors visit major art fairs like Frieze or Art Basel hoping to get their hands on works of art with the potential to bring them profit in the future. But very often they can’t determine by themselves which pieces to hunt. That’s where art galleries come into play. Art specialists are the ones who suggest what a good investment could be, based on many factors. The artistic value of a particular piece is, apparently, the first question. Secondly, the basic rules of supply and demand play an important role here, like in any other business. The more people want a painting, the more expensive it gets. A painting’s place in the history of art and its significance for the culture also add to its cost. And, of course, previous owners and their reputation contribute to the final monetary value of a piece of art.

Collectors need to know which artists are hot and what to focus on. And, the galleries that sell art must be familiar with collectors’ preferences and buying habits, so they can invite the right people to auctions. In time, connections and relationships develop, and most often everybody goes home happy. Well, almost everybody. While galleries get art sold at record prices, and entrepreneurs buy the pieces they aspired to, artists who create art remain empty-handed. Seems a little unfair, doesn’t it?

Where Are the Artists in This Equation?

While their work is selling for tens of millions of dollars, artists typically don’t see a penny of that money. How is that possible, anyway? Well, artists benefit only from the so-called first sales, which is when a collector buys from the gallery or directly from an artist. Once that transaction completes, the collector or the auction house that bought the work benefits from reselling. The more the price of an art piece changes, the more the price grows – and that’s when we start seeing seven-figure amounts.

On the other hand, artists benefit from these resales indirectly. When a piece sells at an auction for a seemingly high price, initial prices must rise. Thereby, the artists can hope that they’ll get more money with their next work. It seems more like a consolation prize than like a real advantage, since many artists get a proper opportunity only once. If they don’t take advantage of it, they may never get a chance to reach to the top-tier buyers.

At the very end, it becomes evident that the rich are going to get richer, and that the collectors are going to be paying more and more, while only a handful of artists will benefit from that. Others will fight to survive, hoping that they’ll get noticed and that one lucky moment will change their destiny. We at ARTDEX have a mission to support the under-represented emerging art and cherish the value of every art because of its power and not because of its market value.

A few years ago we asked the question: “Why is Art so Expensive?” and got some conflicting answers. Speaking of art and money in the same context is most often uncomfortable; still, one is unchanged: the art world is getting more and more linked to unimaginable sums as the time passes.

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)