Feet, what do I need you for, when I have wings to fly? – Frida Kahlo

We’ve all heard their names — the famous female artists that influenced generations that followed. Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, Louise Bourgeois, Yayoi Kusama, Rosa Bonheur, Mary Cassatt — chances are, you are at least somewhat familiar with their work and their artistic vision. Women artists who changed history and the art world should be celebrated for their fearlessness, perseverance, and courage to speak up for themselves and their commitment to the craft.

Even though we would need several lifetimes to properly pay homage to all the influential women artists who left a mark on art history, we have picked out four to discuss in this post. These remarkable women have defied societal expectations stacked against them to stay true to their character and their creativity. From Realist and Impressionist to Surrealist and Abstract Expressionist, from painters and printmakers to sculptors, we are honoring women in the arts who inspired the world.

Rosa Bonheur (1822 – 1899)

In the 19th century, Rosa Bonheur achieved fame and recognition on an unprecedented scale and became the most famous female painter of her century. Her love of painting animals grew from an early age — she was as young as 19 when her first work, titled, Two charming groups of a goat, sheep, and rabbits (1841), was exhibited at the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The painting Ploughing in the Nivernais (1849)won her a medal before she turned 30 years old.

Bonheur was a master of realism. Her specialty was horses and animals in the pastures, and her masterpiece was doubtlessly The Horse Fair (1852-55). Over 8 feet high and 16.5 feet long, the monumental painting takes up an entire gallery wall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York. While working on this painting, Bonheur visited Paris horse market in a span of a couple of years, even though it was unusual for women to do so. As an animal painter, she even obtained police permission to wear male clothing to the horse market and animal slaughterhouse, not only to prevent harassment she often received, but also to resist the traditional gender norms. Bonheur throughout her career preferred pants, shirts, and ties to skirts and dresses, which gave her a sense of identity true to herself.

She was notoriously indifferent towards men and did not appreciate their dominant role in the family or societal circles. “As far as males go,” Rosa Bonheur declared, “I only like the bulls I paint.”

An unusual element to Bonheur’s craft was that she painted en plein air, unlike most other well-known academic painters of the 19th century. With her global fame, even “Rosa dolls” were made in her image that reached far and beyond France. Bonheur influenced a new era of painting, in which artists slowly transitioned from their studios to the outdoors, and ushered in the movement of Impressionism.

Bonheur was buried together with her lifelong partner, Nathalie Micas at a cemetery in Paris. Upon Bonheur’s death, her later companion, the American painter Anna Elizabeth Klumpke became her sole heir and later joined Micas and Bonheur and was buried in the same cemetery.

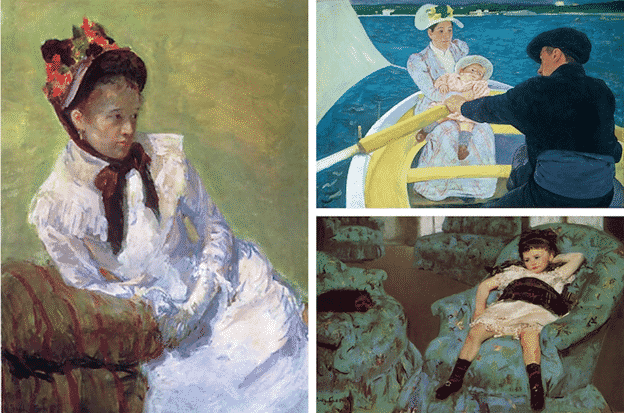

Mary Cassatt (1844 – 1926)

The only American artist invited to exhibit with the French Impressionists, Cassatt was a woman ahead of her time. She rebelled against the patriarchal norms that tried to ban her from studying art and enjoying all the benefits of her male artist peers. She enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts despite her father’s wishes, and when she found their methods of teaching too slow and patronizing, she fled to Paris to seek education from private tutors.

Much like her Impressionist friend Berthe Morisot, Cassatt painted women and children in their quiet, intimate moments, as viewed in The Child’s Bath (1893)and Louise Nursing Her Child (1898). Under the guidance of her close friend Edgar Degas, Cassatt experimented with different materials and mediums, becoming quite proficient in pastels. Later on, her style evolved from typical Impressionist brushstrokes to flat and monochromatic color tones, inspired by the Japanese Ukiyo-e art.

Alongside her undeniable talent and painting and print skills, Cassatt was also an outspoken feminist who did not let herself be dismissed by men. Mary Cassatt was never married and was well aware that she would have to sacrifice her own artist career if she did. She took part in recreating what it meant to be a ‘New Woman’ in the 19th century, taking cues from her mother, who was principled and socially active. As in the portrait of her mother, Reading “Le Figaro” (1878)showing Cassatt’s mother reading a mainstream daily newspaper, often associated with masculine and intellectual activity.

Even when she could no longer create art because of her deteriorating eyesight in her later years, Cassatt continued supporting the women’s suffrage movement. Throughout her life, she advocated for women’s rights and represented them in her artworks with a sense of dignity and depth that male artists often could not convey.

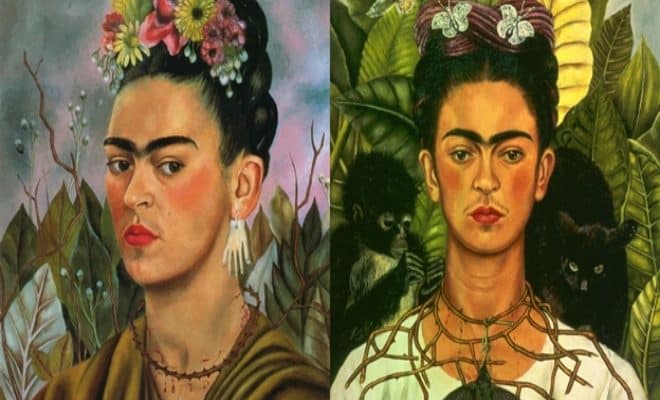

Frida Kahlo (1907 – 1954)

An artist who could transform pain into beauty, Frida Kahlo is a legacy. The severe injuries she sustained in a bus accident at the age of 18 left her in chronic pain for the rest of her life, but that didn’t stop Kahlo from expressing through art — her eccentric, groundbreaking magical realism and fantasy, mixed with strong autobiographical elements unique to her own identity.

During her lifetime, Kahlo was mostly known as the wife of Diego Rivera, a celebrated Mexican painter and muralist. It was only after her death and thanks to feminist art movements that Frida Kahlo’s body of work received the recognition it deserved. She became famous for exploring the concepts of identity, gender, and death and pushing the boundaries of realism and surrealism in her naïve folk art style. She was particularly aware of her mixed European-Native heritage that filtered onto her canvases, as seen in My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree) (1936).

Kahlo’s self-portraits are abundant with symbolism. One such example is the Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940), where Kahlo represented her emotions with a bird, a cat, a monkey, and thorns around her neck that made her bleed. The bird — a common thread in her work — is dark and lifeless, seemingly representing her own broken spirit. The Broken Column (1944)clearly depicts Kahlo’s excruciating condition and the pain she suffered every day. Due to her spine problems, Kahlo had worn cast and metal corsets throughout her life.

Frida Kahlo was the epitome of a strong woman who defied the odds in more than one context. Her physical ailments and emotional challenges didn’t stop her from carving out a niche of her own artistic identity and becoming an icon for feminists and LGBTQ+ movements, as well as an emblem for Mexican and indigenous cultures and traditions.

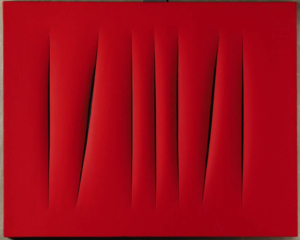

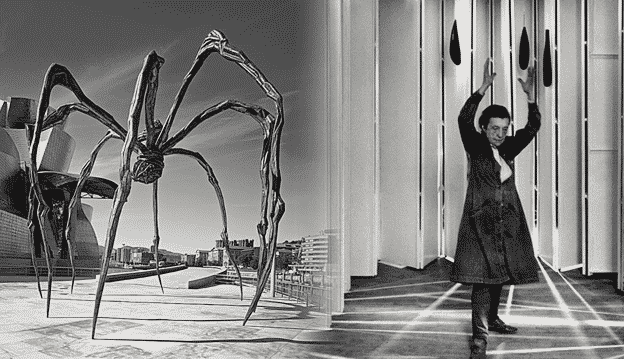

Louise Bourgeois (1911 – 2010)

I need to make things. The physical interaction with the medium has a curative effect. I need the physical acting out. I need to have these objects exist in relation to my body. – Louise Bourgeois

Even though she commanded multiple art styles — such as Abstract Expressionism, Feminist art, and Surrealism — Bourgeois wasn’t formally affiliated with any particular art movement throughout her art career, which span eight decades from the 1930s until 2010. As one of the greatest figures of modern and contemporary art, Bourgeois played with versatile and unconventional visual symbols in her painting and printmaking, as well as uniquely personalized shapes and materials in her sculptures which gave powerful insights to her troubled memories from the past. Bourgeois dove deep into the human psyche and explored the raw emotions of jealousy, anger, abandonment, loneliness, and fear through her artworks.

As a part of recurring themes, domestic life and the home often occupied Bourgeois’s work throughout her career. Her most recognized series of paintings in this theme is the Femme Maison (1946-47) that focuses on the female identity. In these series, the heads of the depicted women are replaced with houses and buildings, as though their domestic obligations are suffocating them, and trapped inside a house. “She is totally self-defeating because she shows herself at the very moment she thinks she is hiding,” Bourgeois says of the women in her series.

Bourgeois created installation works such as Cells (1989-93), a series of enclosures that invited the viewer to peer inside and contemplate the notion of voyeurism. While her Cell structures often reveal domestic objects, Bourgeois constantly challenged the conventional role of women in 20th century society, exploring the female identity throughout her artistic career. In the late 1990s, she turned to the shape of the spider as inspiration. Her largest sculpture of this kind is Maman (1999), a spider standing over 30 feet high. It is made of marble, bronze, and stainless steel, and it represents an ode to Bourgeois’ mother and how she weaved a web to protect her children and family.

Her outlandish sculptures and installations (and paintings, early on) were a way for Bourgeois to work through her emotions and struggles at different moments in her life. She wasn’t afraid of leaving bits and pieces of herself in her art as she worked through the traumatic memories of her mother’s death and father’s adultery in a way that made sense for her through her creative journey.

After all, as Bourgeois declared in her artwork from 2000, “Art is a guarantee of sanity.”

Conclusion

Given that men mostly dominate the world of art throughout history, it is no surprise that by discussing successful women in art, we are also faced with exposing women’s vulnerability, their position in society, and the ever-present battle between feminism and sexism.

There is no doubt that famous female artists in art history, such as Rosa Bonheur and Mary Cassatt, had to be bolder in their demands, going so far as to ask for permission from law enforcement to break out of the female stereotype and remained single for pursuing her art career. In turn, women painters of the 20th and the 21st century were faced with perhaps subtler on the surface yet different sets of obstacles and challenges, nevertheless.

What we can learn from women who changed the art world is that an artist does not have to apologize for who they are and what they contribute to the community at large. Every point of view matters, and every aesthetic and creative tendency can find its place. From the most prestigious art museum exhibitions to small local solo shows, every woman artist should be proud of her work and her commitment to her craft, regardless of what style or what medium she is using, no longer bound by the archaic gender norms history has placed them as before.

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)