I’ve been absolutely terrified every moment of my life – and I’ve never let it keep me from doing a single thing I wanted to do. – Georgia O’Keeffe

Pioneer — someone who is the first to explore an area, a concept, an idea. The art world — in any historical era — is fluid and ever-changing. There is no one correct way to do art; there is no art technique or vision that cannot be altered, expanded on, or completely transformed. Even so, ever so often, we are met with pioneers in art that shift the tides and bring about a new era, a new normal and art movement that the public has yet to experience.

Pioneering female artists aren’t as uncommon as one would believe. However, there have been strong women who dedicated themselves to their artistry and career and have left their mark on art history, changing the landscape of art in unpredictable yet fascinating ways and paving the way for each aspiring woman artist for future generations. In this post, we are going to highlight several pioneering women artists without whom the art community wouldn’t have been the same.

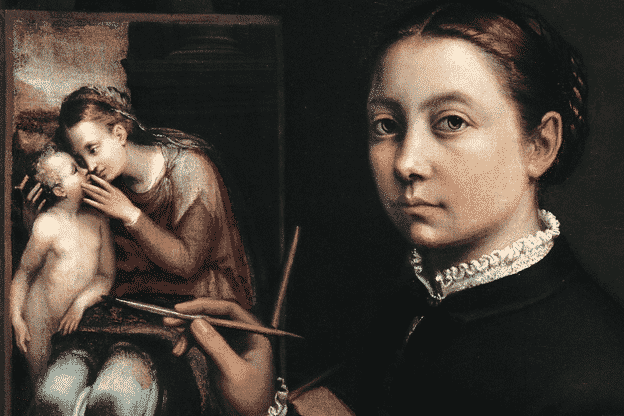

Sofonisba Anguissola (C. 1532 – 1625)

The 16th century Europe, or anywhere else for that matter, did not see many women painters. Sofonisba Anguissola had set a precedent for women studying the arts, as she was the first female apprentice with local painters in Cremona, Italy. Anguissola was talented, skilled, and hard-working, and she was determined to succeed in her artistic endeavors.

And succeed she did at becoming one of the pioneering and respected women painters in her lifetime. Throughout her career, Anguissola traveled to Rome, where she met Michelangelo, then to Madrid, Spain, where she became the official court painter to King Philip II. She would also explore Sicily, Pisa, and Genova, continuing her work as one of the most successful artists of her generation during the Italian Renaissance.

Anguissola’s style belongs to the late Renaissance movement, infused with a sense of charm and delicacy. She was well-known for her self-portraits, such as the one from circa 1560. Among her finest works, one could also include portraits of her family, an example of which is the Family Portrait, Minerva, Amilcare and Asdrubale Anguissola (1557).

Giorgio Vasari, a painter himself and one of the most important writers and historians in Renaissance art, highly praised Anguissola’s work. “She has not only succeeded in drawing, coloring, and copying from nature, and in making excellent copies of works by other hands,” he wrote in his seminal book The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, which in fact is the foundation of art historical writing. Vasari continued “but [she] has also executed by herself alone some very choice and beautiful works of painting.”

It is thanks to Anguissola’s relentless pursuit of her superior artistry and her artistic liberty that women succeeding her had the opportunity to set on their own creative ventures.

Berthe Morisot (1841 – 1895)

Along with Mary Cassatt and Marie Bracquemond, Berthe Morisot was considered one of the Three Grand Dames of Impressionism. Born into an affluent family, Morisot was fortunate to receive an enviable art education in her early life. Aside from painting, young Morisot would also pose as an art model for Édouard Manet and eventually married his younger brother Eugène Manet.

As one of the founders of Impressionism, Morisot offered an important and uniquely feminine perspective in the Impressionist movement. She would paint women and children in domestic, intimate scenes, like the painting of her older sister at the park in Reading (1873)and at home in The Cradle (1872). While male Impressionist artists portrayed high-class women as central figures, Morisot would extend the same courtesy to house servants, cooks, and maids. In The Dining Room (1875)is an example of how she didn’t discriminate when it came to women of different social standings.

Even though Berthe Morisot enjoyed financial stability and opportunities not often (or ever) awarded to most women in her time, she still felt as though she was in an inferior position to her male peers. “I don’t think there has ever been a man who treated a woman as an equal,” she wrote in her diary at one point, “And that’s all I could have asked for — I know I am worth as much as they are.”

Unbeknownst to her, through her perseverance in her art career and determination to keep up with the male Impressionists, she paved the way for women of future generations to explore their own artistic journeys.

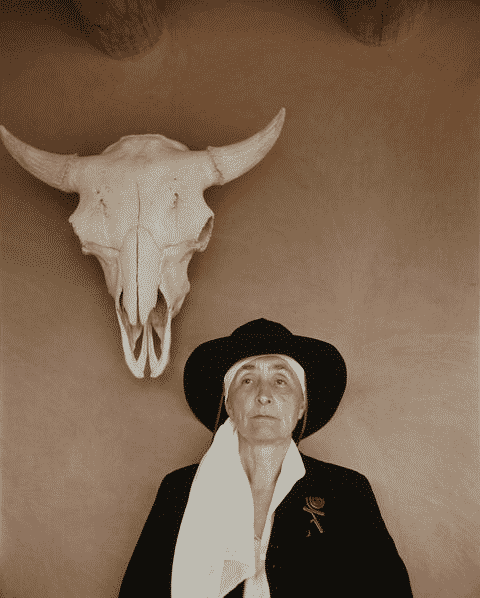

Georgia O’keeffe (1887-1986)

One of the most famous American women artists, Georgia O’Keeffe is a symbol of modernity. She studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League in New York, and she was profoundly influenced by painter, photographer, and printmaker Arthur Wesley Dow. The aesthetic philosophy of Dow, a painter influenced by Japanese art, was a major catalyst for O’Keeffe. He taught O’Keeffe how to view the world differently, and art as a craft, and how to develop her own art language like none other.

“His idea was, to put it simply, to fill a space in a beautiful way,” O’Keeffe explained at one point.

And she certainly did that. While she was mainly considered an Abstract Modernist, her artworks could also be seen as borderline Surrealism or Precisionism. O’Keeffe breathed unique life and soul into her paintings, beginning with the flowers that would become the defining theme of her artwork. Series 1 No 8 (1918)and Black Iris (1926)are examples of how she would enlarge the flowers to ‘audacious’ proportions that left her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, a photographer and most influential modern art promoter, as well as the public, in shock.

What set O’Keeffe apart from her contemporaries was how she was bold and daring in her depictions, regardless of whether she painted flowers or Southwestern themes, such as in Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue (1931). She didn’t shy away from combining the styles of abstractionism and realism, as evident in Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II (1930). She was a modern woman who followed her own vision, her one-of-a-kind style, and who didn’t let the world confine her to a mold. To this day, a floral painting by O’Keeffe set a highest price record at $44.4m for an artwork by a female artist.

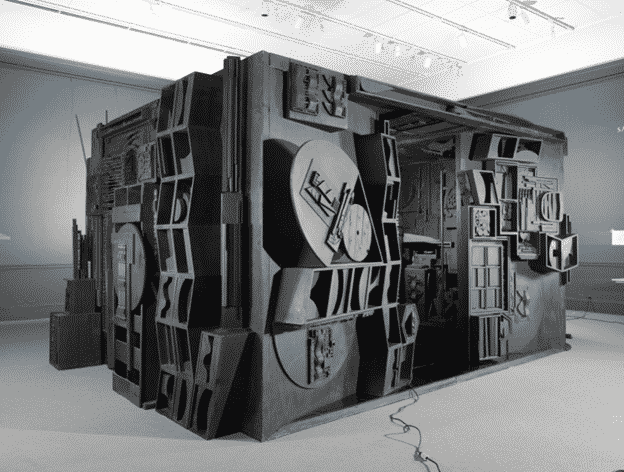

Louise Nevelson (1899 – 1988)

The famous quote, “I’m not a feminist. I’m an artist who happens to be a woman,” comes from Louise Nevelson, a critical figure in the feminist art movement. A sculptor who created striking assemblages of wooden structures, wall pieces, and outdoor sculptures also in steel, aluminum, Plexiglass, and other materials, Nevelson played with the ideas of femininity and masculinity, heedless of the sexist remarks she was receiving for her work associated with her gender identity.

Even though her artistic peers — Theodore Roszak, David Smith, Alexander Calder — all utilized metal in their sculptures, Nevelson mostly opted for wood instead. Her father was a woodcutter and lumberyard owner, which reflected her background in her preferred choice of material. Nevelson’s most renowned sculptures are her wall sculptures — dark and stout structures that resembled monumental totems filled with found wooden scraps like moldings, spindles, and broken furniture parts. Up until 1959, these wall sculpture pieces were made from painted wood, like the Black Wall (1959). She would spray-paint them black and describe it as a “total color.” “It wasn’t a negation of color. It was an acceptance,” Nevelson said. “Because black encompasses all colors. Black is the most aristocratic color of all.”

Later on, she would experiment with materials like plexiglass, in Night Leaf (1969)and white color, in artworks such as Dawn’s Presence (1972-75).

Inspired by Cubism and Pablo Picasso, as well as African art, Native American and Mayan art, Nevelson created abstract sculptures in an effort to explore her own complicated past and Russian heritage, as well as present and unknown future. She was a formidable icon who pushed past those who sought to undermine her work and herself as an exceptional artist of her own league. Her constant goal was to separate herself from the label ‘female artist’ and simply become an ‘artist.’

Yet Nevelson did a lot more than that. Through her hard work and unconventional material and color choices, she established herself as one of the most important artists in 20th-century American sculpture.

Conclusion

It would be a disservice to all other female artists who paved the way for those who came after them to say that this is close to a comprehensive list. Names like Artemisia Gentileschi, Hilma af Klint, Lavinia Fontana, and more, certainly deserve their own recognition in this context. Without bold, empowering women in the arts, the world would have been robbed of groundbreaking artworks and shifts in the perception of art. Not to mention that there would be far fewer female artists today who could hope to be as successful as their male counterparts.

To speak about pioneering women in art, it is to speak of women’s history, of breaking through stereotypes of a woman as a delicate, fragile being destined only for the domestic and child-rearing duties. To speak about bold women painters and daring women sculptors, it is to speak of feminism and sexism, of resolute and courageous women pursuing their artistic career who did not let anything stop them from chasing their dreams and mastering their sublime artistry.

To learn about women in art history is to reinstate and learn about women of today. The society as a whole has made progress, but equality and fairness is still out of reach more often than not. Led by the examples of Sofonisba Anguissola, Berthe Morisot, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Louise Nevelson, women artists should not hesitate to work for their goals and unapologetically be themselves, no matter their circumstances and obstacles may continue to persist.

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)