“I think I’m a transitional figure. If anything, I would call myself a post-structuralist, not a postmodernist. I’m involved with evolution of form, the connection where space and matter meet. One of the things that form constantly has to do is reach a point where it pushes back against content.” – Richard Serra

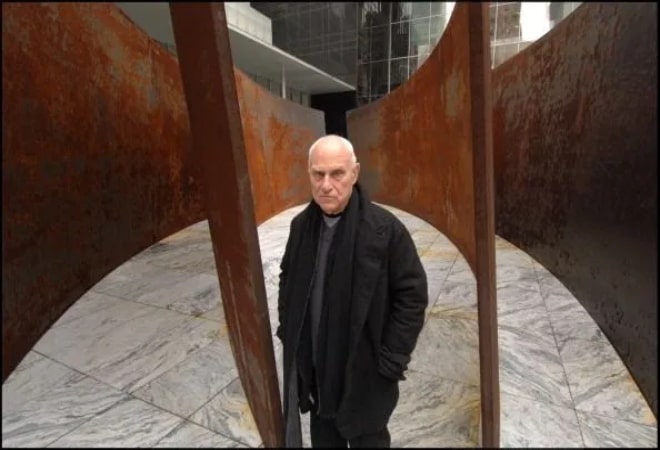

Best known for his large-scale, walk-in steel sculptures, American sculptor and minimalist Richard Serra has been grappling with steel since he was a teen. Born in 1938, Serra was a middle child whose father was a candy factory foreman who also worked in steel mills. His father’s work as a pipefitter served as Serra’s early influence and inspiration for utilizing steel as a medium. Working in steel mills ultimately became how Serra supported himself through school.

Art critic Robert Hughes, who the New York Times once described as “the most famous art critic in the world,” refers to Serra as “not only the best sculptor alive but the only great one at work anywhere in the early 21st century.” However, Serra didn’t start his career as a sculptor, nor did he immediately take the steel he was already so familiar with and turn it into his medium of choice until later on.

Serra: The Early Years

Serra studied at the University of California-Berkeley, University of California-Santa Barbara, and the Yale University School of Art and Architecture. At Yale, Serra, along with other students, was asked to proof Josef Albers’ book, The Interaction of Color. The German-born American artist, theorist, and educator, Albers, is best known for his iconic paintings from the Square series, invaluable teachings, and innovative contributions to color theory.

It was during the time Serra spent proofing Albers’ book and learning the design course’s experimental approach that he would come to realize that “matter imposes its own form on form.” Serra would describe the experience in a 2006 interview: “Working your way through a problem with a specific material is not theoretical. For me, the choice of material is subjective and accounts for one’s sensibility and intuition.”

Serra went on to describe his time at Yale as humbling and the point where he had to learn what it truly meant to be a painter. Painting paved the way for an opportunity to participate in a rotating traveling fellowship where Serra was able to go to Paris in 1964. The following year, he received a Fulbright fellowship to study in Italy. However, it was at this point that he dropped painting to focus on working with stuffed and live animals, which included a live pig, chickens, and rabbits.

The Transition to Steel

It wouldn’t be until the late 60s that Serra would shift his focus once again, transitioning to make his first sculptures – abstract pieces that were made of unconventional materials like rubber and fiberglass. And in 1969, he would revisit his tradesperson roots to began assembling structures out of steel, stone, wood, and lead.

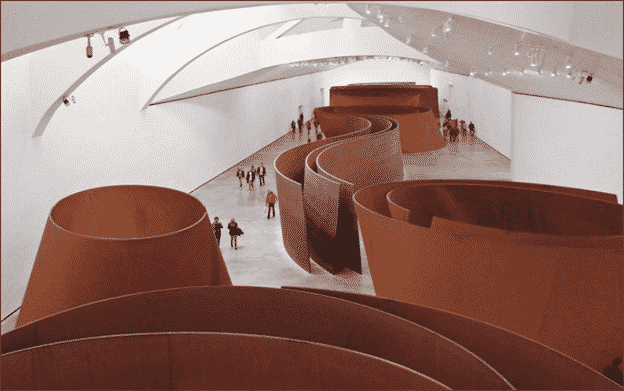

Knowing the potential of steel, Serra departed from other materials. And in the 70s and onwards, Serra would focus entirely on massive, site-specific steel installations made with the intent to dwarf its spectators and encourage interaction and immersion. One of his most notable works is the Torqued Ellipse series, installations that seemingly defy gravity and space.

Serra sat down with Co-Founder and Artistic Director of The Brooklyn Rail, Phong Bui, to explain his life and work. “I came to steel with the knowledge of its potential for construction. That knowledge gave me an advantage in terms of making sculpture, although I wasn’t interested in sculpture per se. I was more interested in exploring different ways of constructing and principles of tectonics on a very basic level.”

In the 1980s, Serra found himself in the center of a public controversy over his piece titled Tilted Arc. While it was the government that approached him to create the work for downtown Manhattan’s Federal Plaza, the unveiling of the piece in 1981 was met with sharp criticism. The monumental sculpture was said to disrupt rush hour and the pedestrians who had to cut through the plaza daily. To the dismay of art lovers, the 120-foot-long, 12-foot-tall Tilted Arc was ultimately disassembled in 1989.

Today, Serra has a permanent installation at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. The highly acclaimed The Matter of Time is described by the Guggenheim as a “dizzying, unforgettable sensation of space in motion.” The minimalist structure is a collection of eight pieces of torqued ellipses made of COR-TEN steel. Composed of seven sculptures, the structure towers 14 feet high with steel sheets that are up to 50 feet long.

One of the components of The Matter of Time is Snake (1994-1997). Snake was commissioned for the inauguration of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, and The Matter of Time was positioned around it, comprised of other pieces from the Torqued Ellipse and Torqued Spiral series. Weighing 180 tons, Snake consists of three steel blades that create a curved path that invites viewers to walk through and around them.

Now 80, Serra boasts a career that spans over 50 years and a spatial and temporal approach that evolved over time. In 1994, Serra received the Japan Art Association’s Praemium Imperiale prize for sculpture. In 2000, at the 49th Venice Biennale, he won the Golden Lion for contemporary art. In 2008, he had the honor of being the second artist to participate in Monumenta to create an original exhibition.

In 2010, Spain awarded him with the Prince of Asturias Award for the Arts. And in 2015, Serra received France’s highest honor, the insignia of Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor – an honor bestowed upon him for his collaboration with French art institutions and contributions to contemporary art.

From September 17, 2019–February 1, 2020, Richard Serra: Reverse Curve will be at West 21st Street in New York. Four new forged-steel sculptures of varying heights and diameters will be available for viewing at the West 24th Street gallery, while the 13-foot high, 99-foot long Reverse Curve can be appreciated at the West 21st Street gallery. There will also be a 3-day retrospective of Serra’s films running from October 17th-19th.

“Weight is a value forme—not that it is any more compelling than lightness, but I simply know more about weight than about lightness, and, therefore, I have more to say about it, more to say about the balancing of weight, the diminishing of weight, the addition and subtraction of weight, the concentration of weight, the rigging of weight, the propping of weight, the placement of weight, the locking of weight, the psychological effects of weight, the disorientation of weight, the disequilibrium of weight, the rotation of weight, the movement of weight, the directionality of weight, the shape of weight.” – Richard Serra

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)