“You can tell the truth more truthfully than with the truth itself.” – Christian Boltanski

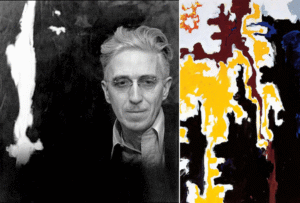

Christian Boltanski, an artist who most often incorporated concepts of memory, chance, and loss in his art, passed away this summer on Wednesday, August 11th. The gallery that represented him, Marian Goodman, has announced his death without a note about a cause. It seems only appropriate to take this moment as a chance to reflect upon his work as a way to pay homage to his contributions to the art world. It circles back to the recent time when asked about his death in an interview for The Times in 2017, “I hope that when I shall be dead, somebody that I don’t know in Australia is going to be sad for two minutes. It would be something marvelous because it means you’ve touched people you’ve never seen, and that is something incredible.”

Memories And Death

Christian Liberté Boltanski was born in Paris on September 6, 1944. His mother, a writer, was a devout Catholic, while his father, a doctor, was of Jewish ancestry. The occupation and liberation of Paris from the Nazi rule made a significant impact on his life — without the latter, he would not have his middle name, and without the former, he may not have been born at the time he was. Moreover, it is not an exaggeration to say that the formative stories of his childhood were the ones his parents and their acquaintances told him of the Holocaust and wartime. Stories that are often associated with the trauma of life and death — an ongoing theme that will reoccur in Boltanski’s art.

He dropped out of school when he was 12; and started creating art early in his teenage years. He began by making plasticine sculptures, moving onto large-scale figurative paintings with time, which he eventually left in favor of photography. This, in turn, grew into a lifelong habit of creating art using abandoned and anonymous pictures gathered from newspapers, police records, and family photo albums acquired in flea markets.

As he was entirely self-taught, it took him a lot of time and effort to find his own way and artistic voice. He made many canvases of paintings and drawings that have been destroyed since and experimented with oddly-themed films. He eventually made his way into the mainstream art world, and by the beginning of the 1970s, he was already finding his way as a conceptual artist.

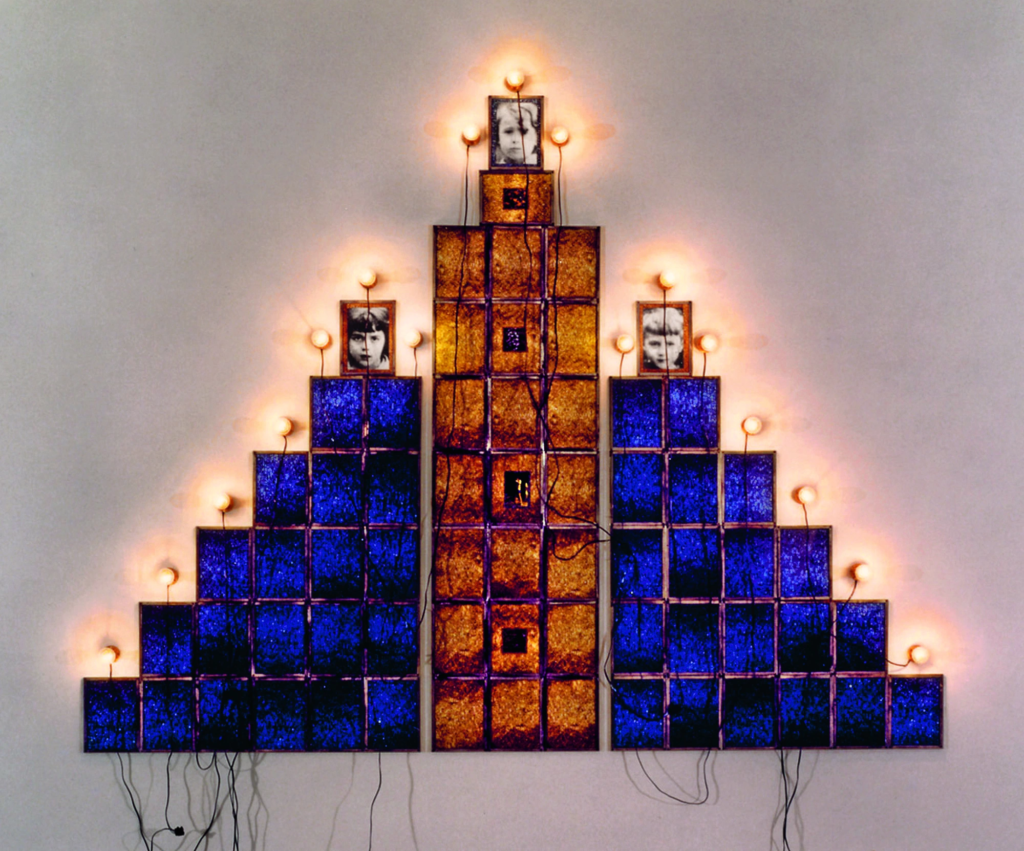

In 1968, at the Théâtre le Ranelagh in Paris, he exhibited his first solo show, La vie impossible de Christian Boltanski (The Impossible Life of Christian Boltanski). The artist collected pictures from various sources, including postcards, newspapers, police registers, and family photo albums, to create large groups or installations that combine ordinary life with high art. This was a beginning for his recognizable art and installations, which are typically presented as shrines to communal cultural rites and events and often deal with loss, memory, and death.

In the 70s, he participated in quite a number of important exhibitions and shows, some of which are Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris (1970) in France; Documenta 5 (1972) in Germany; Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden (1973) in Germany; and Venice Biennale Architettura (1975) in Italy.

Many accolades were bestowed upon Boltanski during his lifetime, including the Praemium Imperiale Award (2006) and the Kaiser Ring Award (2001) to just name a few. In 1977 and 1972, he took part in the Documenta exhibitions, and he was a part of several Venice Biennales, 2011 being the last one.In 2009, however, Boltanski received an interesting commission from an eccentric gambler and Tasmanian art collector, David Walsh — essentially, he ‘sold his life’ to the collector. The piece’s name was “La Vie de CB”, and he was to film Boltanski’s life — a series of 24-hour films of Boltanski working in his studio — until the end of his life. If Boltanski were to live over 8 years since he was commissioned, the artist would be in profit — and that is what he did. Living 5 years over the predicted time, Christian’s lifespan was one of Walsh’s very few miscalculations.

Contemplating What Is Left

Many of his works were seen as reminiscent of the Holocaust — and while that was not the initial intention behind them, he would say that the Holocaust was the event that informed them.

His work was rich in visual and aural impact, and open-ended in its invitation to the viewer to contemplate the past and partake in the present moment — for what has been lost and what endures. One of his most recognizable exhibitions has been “Take Me I’m Yours,” a part of a group exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery, London. Boltanski’s work, called “Dispersion” (1995), was simply a pile of discarded clothing, and visitors were invited to take from the pile freely. According to Boltanski himself, this served to defy the two most common rules in museums — not to touch and not to steal. Additionally, while this evoked a sense of abandonment in adults, children were more than happy to hop into the exhibition and explore — which was yet another of the goals he pursued in his art.

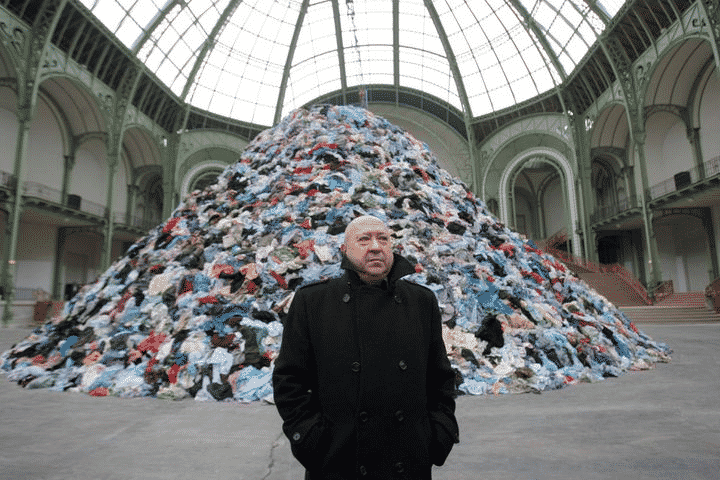

Boltanski has been creating art about lost and found objects for over six decades. His exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville in Paris in 1998 included thousands of items from the lost and found at Grand Central Terminal, while his work “No Man’s Land” consisted of 30 tons of discarded clothing — a work about his enduring theme on loss and remembrance. The former exhibition served to present the sense of sorrow and recollection Boltanski felt when he learned that his elder sister had died. Another one of his notable exhibitions consisted of photographs Boltanski had appropriated from obituaries in a Swiss newspaper. He created a permanent installation at a museum in Bologna, Italy, with the plane’s wreckage as its centerpiece. Since 2008 he has recorded the heartbeats of people all over the world for what he called “Les Archives du Coeur.”

Lost and Found, In Death, In Full Circle

While exploring the topics people usually find grim and foreboding, such as death, he tried to do it with a sense of optimism and even humor — toying with the idea of mortality, memory, loss, and many other concepts associated with death. Moreover, the objects in Boltanski’s work frequently give voice to absent themes and serve as a call to meditation and contemplation for the viewer and observer. This way, he could speak to people of topics or events never touched before — simply by igniting their emotions, memories, or simply associations related to the pieces he was exhibiting. Shortly after his first solo exhibition in 1968, Boltanski published his first books, Recherche et présensation de tout ce qui reste de mon enfance (Research and presentation of all that remains of my childhood, 1944-1950) and Reconstitution d’un accident qui ne m’est pas encore arrivé et où j’ai trouvé la mort (Reconstitution of an accident which has not yet happened and where I found death). Evidently, these books complete the full circle of his journey from which he had embarked — the truth of memories and mortality that no one can ever escape, after all.