While letting go of artworks has allowed museums to improve their diversity of collections, attract more traffic to new works, and help continue operations financially, deaccession will always have its detractors and almost certainly pushbacks. This year in New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art was under scrutiny for its plans to auction off 300 works of Asian art that were donated by philanthropists Florence and Herbert Irving. Because this is not the first time the Met has removed works from collections to sell, many critics believe the Met’s motivations are fueled by profit more than anything.

Deaccession and Disposal: Good or Bad?

The consensus on deaccession and the process of liquidating works to generate funds has long been met with controversy in the art world. Museums build their collections mainly through donations from private donors. Because museums hold the responsibility of good collection stewardship upholding the original wishes and terms from the patrons and their bequests, the removal of any item from the collection to sell would be deemed inappropriate and even unethical.

The practice of permanently removing any work of art from any museum’s collection is so frowned upon that undertaking one involves many complex steps and procedures that need to honor well-defined deaccession principles and guidelines set by individual institutions. In the U.S., deaccessions from a museum’s collection must also conform to the Association of American Museum Directors’ (AAMD)Professional Practices in Art Museums and AAMD’s Policy on Deaccessioning.

For a deaccession to take place, the museum needs to justify its decision, thoughtfully accessing the legal and ethical consequences of their actions. Howto dispose of deaccessioned works, how the process will be documented, and how the funds from deaccessioning will be used are all taken into consideration. There’s also the issue of whether to notify the donors or their estates – and, of course, how to address the outrage from the public and art community who may believe that selling a donated work to benefit the museum is a distasteful practice.

The Trend to Deaccession Works to Diversify

In early 2019, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) defended its decision to deaccession Untitled (1960), a prized Mark Rothko painting that came to the museum as a gift from Peggy Guggenheim. SFMOMA fetched $50.1 million for the painting at the Sotheby’s contemporary evening sale.

SFMOMA says the deaccession was necessary to gain funds that would allow them “to broadly diversify its collection, enhance its contemporary holdings, and address art-historical gaps.” Just a few months later, the museum announced its acquisition of 11works from various artists, including Frank Bowling, Kay Sage, Alma Thomas, Barry McGee, and more.

SFMOMA hasn’t been the only museum to undertake a deaccession that was meant to fuel new purchases. In 2018, the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) deaccessioned seven works of white artists, including paintings by Warhol, Franz Kline, and Kenneth Noland. Described by BMA’s museum director Christopher Bedford as “an unusual and radical act,” letting go of works by white males would allow them to build a “war chest” that included works by underrepresented artists, including works by female and African American artists.

Bedford says that the decision to deaccession works was the only way it could stay relevant and the only “way to fulfill all of our capital aspirations, exhibition-making aspirations, and raise money to be competitive in the contemporary art market.”

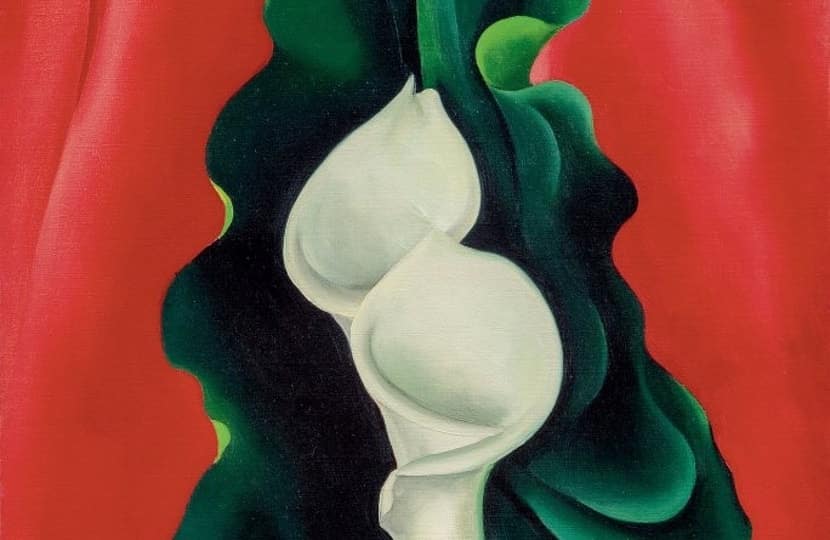

Also, in late 2018, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe deaccessioned three paintings, including O’Keeffe’s Calla Lilies on Red, which sold for a combined sum of over $23.3 million at Sotheby’s. Robert A. Kret, O’Keeffe Museum director, released a statement ahead of the sales, stating, “Removing an artwork from the collection is never an easy thing for any museum to do, but it is an integral part of good collections management to continually build and refine our holdings.”

This isn’t the first time the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum has removed works from a collection. The museum deaccessioned Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 (1936) in 2014, which sold for $44.4 million, setting a record for tripling the previous world record for auction price for any work by a female artist.

However, deaccession decisions have sparked outrage for years with a deaccessioning controversy for every era. SFMOMA, BMA, and O’Keeffe weren’t the first museums to practice deaccession, and they certainly won’t be the last, especially now that diversifying collections is the only way museums can stay relevant and fill the missing links in their offerings.

Defending Deaccession

When is deaccession justified? The AAMD’sPolicy on Deaccessioning stresses that all deaccession decisions should be made with “great thoughtfulness, care, and prudence” and to put donor intent and public interest first.

The policy outlines the criteria for deaccessioning and disposal. Deaccessioning may be contemplated if the work is of poor quality, the work is a duplicate, or the work is determined to be fake or fraudulent. Duplicate works that are part of a series and have no value to the museum holdings may also be considered for removal.

Works that are in poor physical condition and not worth the restoration may also be candidates for deaccession. The museum may also permanently remove an object if it can no longer care for the piece because it lacks the storage or resources to meet its unique needs.

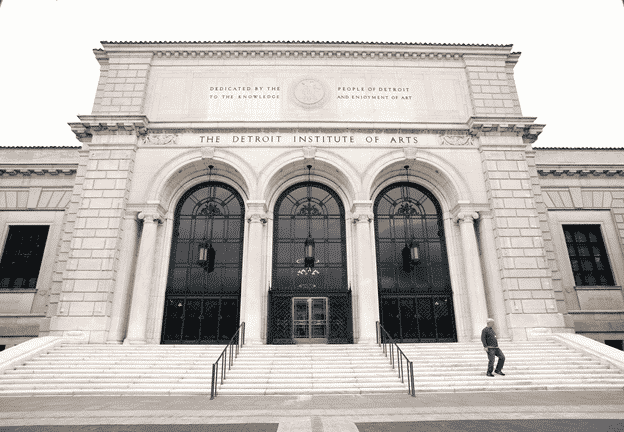

Possession of work that may have been stolen or illegally imported is also grounds for deaccession. Such is the case with the Met as it currently tries to determine whether the 15 prized antiquities it acquired some thirty years ago passed through the hands of one of the most prolific smugglers, Subhash Kapoor. Kapoor, who stole an 11th-century bronze statue of a Dancing Shiva from an Indian temple and sold it to the National Gallery of Australia for $5.6million, is now on trial for running a $145 million smuggling racket.

But of the eight primary acceptable reasons for deaccession, two appear to be the most used today – the work is no longer aligned with the museum’s mission, and the work needs to be sold to refine and improve its collection.

The selective deaccessioning of works may be for the museum’s survival and necessary to promote diversity and inclusion; however, the act will always be met with stern criticism. There will always be those who will question the museum’s motivations – and with good reason. Museums have a moral responsibility and are obligated to serve the public interest. Deaccessioning works of art with the intention to profit, fill their reserves, pay off debt, and replenish endowment disrespects “public trust” and certainly does not honor the donors who gift and bequest works to ensure long-lasting legacies.