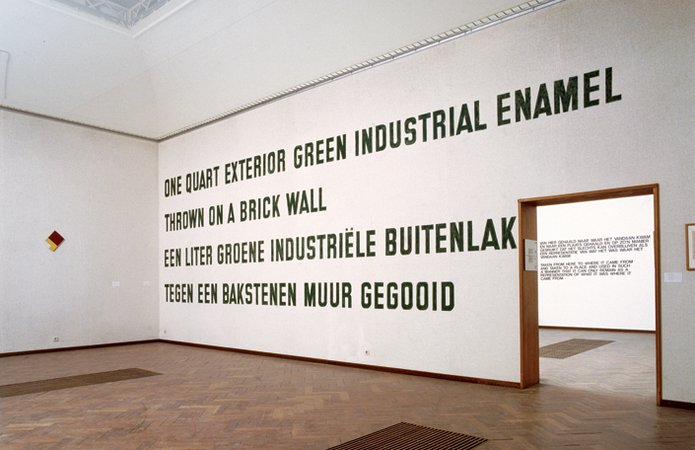

“Because Mr. Weiner’s words are mutable, appearing in one state and then another, they are not only continually remade but also renewed.” – New York Times critic Roberta Smith

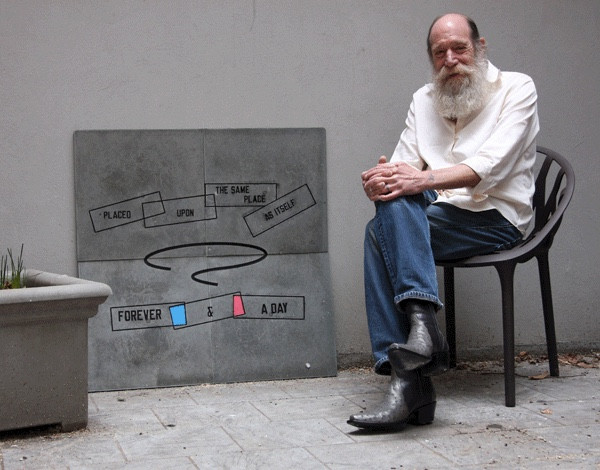

On December 2nd, 2021, the world bid a final farewell to Lawrence Weiner, the American artist who was widely recognized as the “godfather” of the Conceptual art movement of the 60s and 70s. Weiner is best known for his enigmatic text-based sculptural installations and revolutionary redefinitions of mediums, including video, audio, and performance art.

In 2019, Weiner quipped with Culturedmag.com, “Here I am. I’m 77 years old and I made it to 77. Whether I’ll make it to 78, I don’t know. I may disgrace myself tomorrow.” Weiner died at 79 in Manhattan, survived by his wife, daughter, and grandson.

Born in South Bronx, New York on February 10th, 1942, Weiner was born to working-class parents that ran a candy store. As a child, Weiner would create chalk drawings on the sidewalk outside of his parents’ shop, romanticizing his platform choice by saying, “You grow up in the South Bronx, you learn, you use what you have, and if it’s the wall and it’s a floor, you use it.”

Weiner’s younger years involved a series of odd jobs, including working part-time at the docks at age 12 and at an oil tanker in his teens. At 16, he graduated from the prestigious Stuyvesant High School — despite often skipping school to join civil rights marches and anti-nuclear demonstrations. Weiner would spend less than a year at Hunter College where he studied philosophy and literature. After dropping out of college, Weiner began traveling throughout the country.

Art Interventions: Distinction Between Art and Anti-Art

By 1960, 19-year-old Weiner had made his way to California where he created what he would consider as his first major work. Detonating four explosives in a field in a Marin County, California state park, Weiner made “Cratering Piece” with the help of friends. The aftermath of the explosions were “anti-sculptures” — cavities left in the earth that became the first of Weiner’s art interventions, subversive works that existed outside the traditional art world.

Weiner’s breakthrough with interventions came in the late 60s after realizing that he did not need to rely on physical construction to validate an artist’s intention. The epiphany came after his outdoor sculpture Hay, Mesh, String was mistaken for surveying equipment by college students who played touch-football on the field on which the installation stood. What Weiner considered unobtrusive work consisted of a series of stakes that were connected by a grid of twine. Instead of walking around the work, the students cut down the twine. Realizing that the work would have been less blatant as art by using language to describe the piece, Weiner renamed it A Series of Stakes Set in the Ground at Regular Intervals to Form a Rectangle—Twine Strung from Stake to Stake to Demark a Grid—a Rectangle Removed from This Rectangle (1968).

Knowing that the students didn’t recognize the installation as art and dismantled it without intending harm, Weiner wrote a set of principles: “The artist may construct the piece. The piece may be fabricated. The piece need not be built. Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist, the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.” This “Declaration of Intent” would be included in his book of assertions, Statements (1968).

In 2018, Weiner recalled that experience in an interview with the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of America. Weiner said, “It became obvious to me that as long as you can present it, it didn’t matter how. Either you built it, you didn’t build it, you put in language, you didn’t put it in language, as long as it wasn’t a secret.”

Weiner’s Words-on-Walls

It was the unintentional dismantling of his installation that became a motivator for Weiner to make art that reached a wider and more diverse audience through language. He displayed words and statements in public spaces, focusing on creating simple and accessible interactions with viewers.

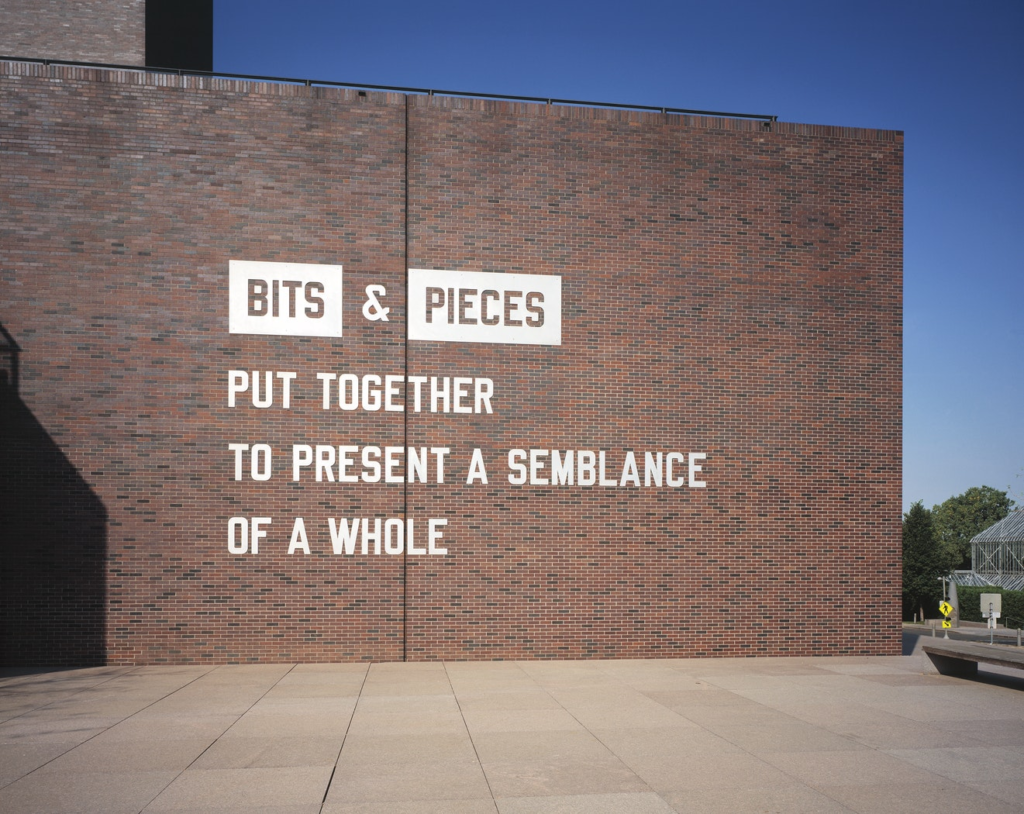

Realizing the power of words to communicate intent, Weiner ruled that the artistic idea was more crucial than who produced the work. By the 70s, his language sculptures, wall installations of profound and descriptive phrases in Sans-serif or Franklin Gothic font, would define his career. To prevent confusion, he chose capital letters and universal grammar. And while he was conversational in languages like German, Dutch, and French, Weiner believed that art was the sincerest form of communication.

Following Weiner’s beliefs, the lettering wasn’t always done by him and often done by a painter with a stencil; what was important was that it complied with his instructions. But what set Weiner apart were his epigrammatic statements, starting with his One Quart Exterior Green Industrial Enamel Thrown On a Brick Wall (1968) and Removal to the Lathing or Support Wall of Plaster or Wallboard From a Wall (1968).

Following Weiner’s philosophies that works of art need not be made by the artist themselves, many of Weiner’s works tended to consist of phrases that described a process or the result of a process. These works included Many Colored Objects Placed Side by Side to Form a Row of Many Colored Objects (1982), Some Limestone Some Sandstone Enclosed for Some Reason (1993), Shells Used to Build Roads Poured Upon Shells Used to Pay the Way, At the Level of the Sea (2008), and White Cloth Stretched to the Limit (2020).

“I think there should be a reworking of the value structure of art. The value is when the artist makes a first engagement with society. The work has the most value. That is the function of the artist. That result.” – Lawrence Weiner

While Weiner still referred to himself as a sculptor, he explains his medium as “language + the material referred to.” Through words, he demonstrated the dimensions of language and how critical viewer interaction was on a work’s influence.

Through the decades, Weiner held many important solo shows. In 1988, he exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, and in 1990, he held a major solo exhibition at Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington DC. Over the next thirty years, Weiner’s work would be mounted in places like the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, Musée d’Art Contemporain Bordeaux, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Deutsche Guggenheim in Berlin, and Nivola Museum in Italy.

Weiner’s contribution to Conceptualism would earn him many accolades, including a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships and a Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1999, he won the Wolfgang Hahn Prize and won a Skowhegan Medal for Painting/Conceptual Art in 1999. In 2012, Weiner was honored for his contributions to conceptual art at the Drawing Center’s Spring Gala. And in 2017, Weiner received the Aspen Award for Art.

In 2020, Weiner defended his choice of font to Interview magazine, reasoning, “I can say what I have to say, and it’s not related to the typeface. A lot of people were able to copy what I did, and that’s good. That’s what art is for. Art is for people to use.”

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)