The overlooked “blur” that linked Dada’s chaos with Surrealism’s dreamworld

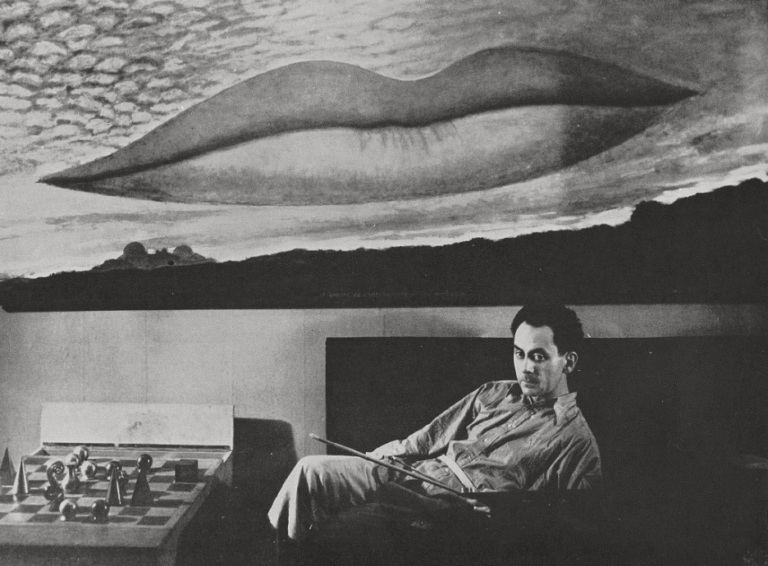

“Man Ray,” the poet André Breton once said, “is the quintessential modern artist — free, inventive, and forever unclassifiable.” That slipperiness is exactly what the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition Man Ray: When Objects Dream brings into focus. Rather than slotting the artist neatly into the canon of Dada or Surrealism, the show positions him as inhabiting a space of uncertainty.

Now on view through February 1, 2026, the Met’s Man Ray exhibition is the first to situate his celebrated rayographs within the larger arc of his work from the 1910s and 1920s. Drawing from the institution’s collection and more than 50 international lenders, the exhibition assembles around 60 rayographs and 100 paintings, objects, prints, drawings, films, and photographs. Seen together, these works reposition the rayograph not as a curious side note but as a central force in Man Ray’s refusal to be bound by categories, and as a key to understanding the fertile “blur” through which he redefined modernism itself.

At the core of this reevaluation lies a half-forgotten phrase: “Mouvement Flou.” Coined by Surrealist poet Louis Aragon, it literally means “the blurry movement” or “out of focus.” As art critic Ben Davis observed, “Despite the fact that I have seen many, many art shows sanctifying 1920s modernism from seemingly every angle, the ‘Mouvement Flou’ is a new one to me.” The term illuminates a brief, transitional moment when Dada’s chance-driven absurdity was yielding to Surrealism’s embrace of dreams and desire, a hinge point of possibility before the avant-garde hardened into manifestos.

.jpg)

Man Ray in the In-Between

Few embodied this liminal energy as completely as Man Ray. Born Emmanuel Radnitzky in Philadelphia, he was an American in Paris who never fully belonged to either side of the Atlantic — or to any single movement. “I do not photograph nature,” he once quipped. “I photograph my visions.” His vision was one of refusal: a refusal to be bound by categories, whether medium, nationality, or avant-garde label.

This refusal played out across his astonishingly diverse practice. In his experimental rayographs, blur became a literal technique: the ghostly shadows of objects pressed onto photosensitive paper without a camera. These works take center stage at the Met, where more than sixty are displayed in an almost celestial arrangement. One striking wall presents Champs délicieux (1922), a grid of twelve rayographs whose floating silhouettes of combs, coils, and keys become what Tristan Tzara once called “objects dreaming.” The display drives home the show’s thesis: here, ordinary things transcend their materiality, suspended in a state between recognition and abstraction.

In portraits of his contemporaries, such as Gertrude Stein, Marcel Duchamp, and Lee Miller, blur often unsettled perception, inserting uncertainty into images that might otherwise have sought clarity. And in objects like The Gift (1921), an iron studded with nails, or Object to Be Destroyed (1923), a metronome topped with a photographic eye, Man Ray blurred distinctions between utility and absurdity, fetish and joke, art and object. “Ambiguity,” art historian Rosalind Krauss has argued, “was not a weakness but a weapon.” Man Ray turned that weapon into a practice.

A One-Man Art Movement

Scholars often frame Man Ray as a key figure within Surrealism. Yet, as the Met exhibition argues, his practice is better understood as what some critics have called a “one-man art movement.” His restless experimentation—photography, film, painting, sculpture, fashion — suggests less an allegiance to “isms” than an ability to slip between them.

Dada’s embrace of chance and irrationality is everywhere in his early collaborations with Duchamp, most famously in the proto-conceptual readymades. Surrealism’s obsession with the unconscious is evident in his dreamlike films such as L’Étoile de mer (1928). But the blur between those poles, where accidents and subconscious associations intertwine, was his most fertile terrain.

The Met exhibition’s curators embrace this hybridity in their installation design. Works are arranged thematically rather than chronologically, with sections titled “Dreams,” “Body,” and “Games,” dissolving linear progression in favor of a network of recurring motifs. The transition between galleries is deliberately fluid, with films projected in semi-darkened spaces where the flicker of Emak Bakia (1926), its silhouettes dissolving into abstraction, spills softly into rooms filled with photographs and objects. The effect is immersive and disorienting, a spatial analogue to the “Mouvement Flou” itself.

Why Blur Resonates Today

It is tempting to see “blur” as a minor footnote in the story of modern art. But as the Met’s curators subtly argue, the concept feels prescient for our own moment. In today’s cultural landscape, categories are collapsing: photography bleeds into digital art, painting converges with performance, AI reshuffles authorship itself.

“Mouvement Flou” reminds us that modernism, too, thrived on uncertainty. The blurred moment between Dada and Surrealism was not about confusion but about openness: an embrace of indeterminacy that made radical invention possible. Man Ray’s genius was to live in that blur, to resist resolution.

One particularly telling moment in the exhibition pairs the iconic Le Violon d’Ingres (1924), Kiki de Montparnasse’s back transformed into a musical instrument, with lesser-known airbrush paintings like Swedish Landscape (1926). The juxtaposition underscores how Man Ray consistently explored translation, displacement, and metamorphosis across media. Even as he “freed himself from the sticky medium of paint,” as he once wrote, he never abandoned the painter’s logic of layering and transformation.

A Radical Ambiguity at the Met

Man Ray: When Objects Dream ultimately reframes him as an artist of radical ambiguity. He was not just the clever maker of Surrealist icons but a figure who reminds us that the most fertile artistic moments occur in-between.

The exhibition’s title, drawn from Tzara’s phrase, is more than poetic, it’s curatorial. By foregrounding “mistakes,” accidents, and the agency of objects themselves, the show invites us to see Man Ray not as an adherent to any single avant-garde doctrine, but as a figure who thrived in the gaps between them.

For the general viewer, this offers a refreshing way to rediscover Man Ray beyond the clichés. For art professionals, it provides a chance to rethink the historical map of early 20th-century modernism, not as a sequence of clean-cut movements but as a continuum of experiments suspended in blur.

Or as Man Ray himself once put it: “I have freed myself from the sticky medium of paint, and am working directly with light itself.” In that light, blurred though it may be, we glimpse not only the possibilities of his time but the unfinished possibilities of our own.