Captivated by The Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s ”principle of nonacquiescence,” an American poet and critic Ezra Pound, along with his publisher friend Jane Heap, whom he helped run the celebrated literary magazine The Little Review (1914-1929), were the biggest champions of the Baroness’s provocative Dada literary and artworks.

Known for unapologetically pushing sexual boundaries, fighting for avant-garde principles, and exposing the irrationality of conformity and capitalism, The Baroness embodied all things Dada. Heap, a significant promoter of literary modernism in early 20th century America, shared The Baroness’s views on confrontational feminism and called Baroness Elsa, “the only one living anywhere who dresses Dada, loves Dada, lives Dada.”

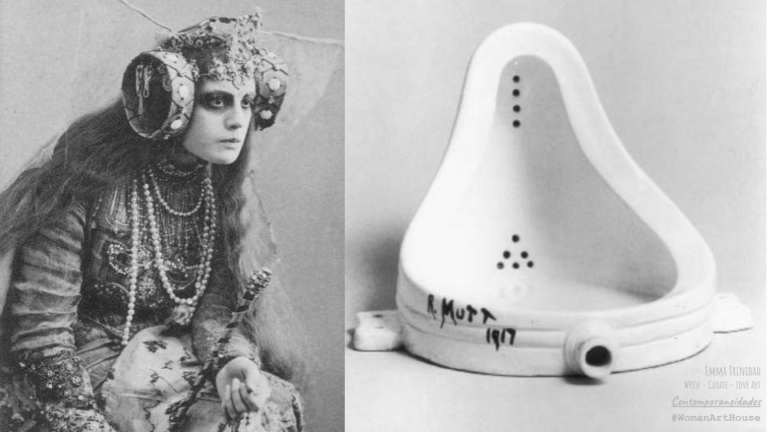

The artist infamous for the upside-down urinal he named the ‘Fountain,’ Marcel Duchamp also admired The Baroness immensely, saying, “She’s not a futurist. She is the future” — quoted in Kenneth Rexroth’s book, American Poetry in the Twentieth Century.

However, Baroness Elsa was perhaps known more for her scandalous and eccentric behavior than her actual poetry and artwork. And some may argue that the way The Baroness brazenly lived her radical life was art itself and the epitome of Dadaism.

The Beginnings of The Baroness of New York Dada

Born as Elsa Hildegard Ploetz in 1874 in Pomerania, Germany, The Baroness was not by any measure a “blue blood,” as the name she would earn later in life would imply. She was the first daughter born into a middle-class family with a mason father and a mother she would later describe as having a “sweetness and intensity – passionate temperament – only softer as I – kept subdued – regulated by custom-convention.”

At only 19, Freytag-Loringhoven lost her mother. And despite dying of uterine cancer, she would blame her tyrannical father, whom she has referred to as a “thick-brained Teuton,” for her mother’s death and pitiful life — particularly the emotional suffering and mental illness that forced her into a sanatorium. One would reason that Freytag-Loringhoven’s feminist views and anti-patriarchal activism were deeply influenced by the contrast between the sweet intensity of her mother and the cruelty of her father.

The Baroness eventually left her scenic hometown on the Baltic for Berlin, the city that would highly influence her future as an artist. She ran in the art circles, including theatre and poetry clubs, which provided her work as an actress, model, and performer. Berlin became the catalyst for The Baroness’s exploration into bisexuality and gender fluidity, allowing her to make many artistic and romantic connections.

In 1901, Baroness Elsa married architect August Endell with whom she shared an “open relationship.” By the following year, she was involved with Endell’s friend, Felix Paul Greve, a novelist and translator who identified as gay when they first met. Divorcing Endell in 1906, The Baroness married Greve the following year. To help her husband escape crippling debt and a fraud conviction, she helped him stage his suicide. Greve moved to the U.S., and The Baroness followed. However, Greve would later abandon her in Kentucky, move to Canada, and change his name. The Baroness’s artistic identity began to take shape during the following years as she began sculpting and creating assemblages with discarded objects, including trash and rusty metals.

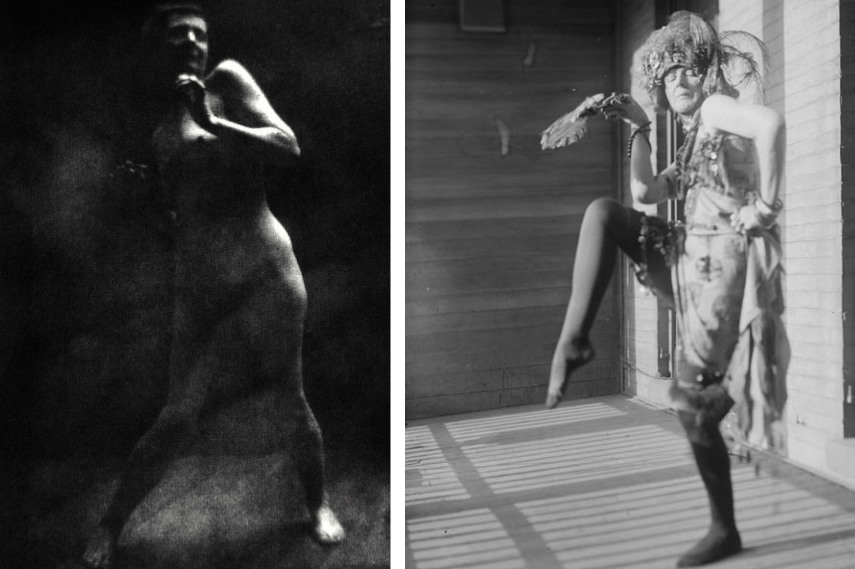

By 1913, The Baroness had moved onto a new city and her third marriage. She married the German baron, Leopold von Freytag-Loringhoven — elevating what was once Elsa Hildegard Ploetz to Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. However, it was another short-lived marriage for The Baroness as her husband would return to Germany, where he committed suicide as a prisoner of war in World War I. To support herself in Manhattan, The Baroness modeled for art students and artists, worked at a cigarette factory, and made a name for herself in the New York Dada scene through her controversial literary work, bizarre fashion choices, and eccentric performances.

The Female Friend Behind Duchamp’s Fountain

Running in the same Dada circles, Baroness Elsa met Marcel Duchamp, best known for his contribution to Dadaist principles and the “anti-art” movement. Many art historians are convinced that The Baroness was the one to supply Duchamp with the urinal that he would exhibit as the ‘Fountain,’ signed R. Mutt, and ultimately, became an iconic readymade artwork for the birth of 20th century conceptual art. In a 1917 letter to his sister, Duchamp recounted that “one of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.” And many still argue that R.Mutt, a name curiously close to the German word for poverty “armut,” was, in fact, Baroness Elsa.

The Baroness made it no secret that she deeply admired Duchamp by performing a piece wherein she rubbed a newspaper article about Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (1912) over her naked body while reciting a poem that closed dramatically with “Marcel, Marcel, I love you like hell, Marcel.” It is said that Duchamp never returned Baroness Elsa’s romantic propositions. The Baroness, however, was not deterred, calling him the “most inventive artist” one moment and the next, teasingly referring to him as “selling himself like a prostitute for art consumption” and “cheap bluff giggle frivolity.”

However, her love for Duchamp would sour over time. And in her later years, The Baroness thrashed former colleagues she’d held a grudge against in her poem “Graveyard Surrounding Nunnery” (1921), which started with lines that included “I loved Marcel Dushit.” And while never claiming to be the true genius behind the Fountain, The Baroness referred to any male artist that she felt didn’t deserve their status and success as having “Marcelled” their way through the art scene.

Art Aggressive, Anti-Bourgeois, and the “First American Dada”

Describing herself as “art aggressive,” Baroness Elsa’s artistic strategy was often compared to Duchamp’s who took ordinary objects and made minimal modifications to present them as readymade sculptures. However, with the conspiracy behind The Baroness’ possible connection to Duchamp’s infamous Fountain, art critics can argue that Dada Baroness was the true catalyst and inventor of readymade art.

The Baroness’ Enduring Ornament (1913) was a rusty iron ring, while her God sculpture (1917) consisted of a cast iron drain trap. In 1918, The Baroness found a piece of scrap wood with jagged lines, mounted it on a simple piece of construction wood, and named it Cathedral. And between 1917-1918, Baroness Elsa mounted a discarded metal spring, curtain tassel, and wire on wood, calling the sculpture Limbswish.

Beyond the readymade sculptures and assemblages made of trash, The Baroness was a poet, visual artist, and performer. In 1917, her poems were championed by the avant-garde The Little Review, crowning her the “first American Dada.”

In 1921, Baroness Elsa starred in La Baronne rase ses poils pubiens (Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven Shaves Her Pubic Hair), a film in which she performs the act as described in the title. And in yet another attack against Duchamp, Baroness collected metal cogs, feathers, and fishing lure to create an assemblage made to allude to Duchamp and mock his female alter ego, Rrose Selavy. The sculpture resembled a peacock ostentatiously displaying its feathers; The Baroness simply called the piece Portrait of Marcel Duchamp (1919).

The Baroness lived and breathed the anti-bourgeois lifestyle. On a typical day, she was seen in eccentric clothing, including a bra made of tomato cans, accessories made of found objects, and a birdcage around her neck — with live canaries inside to complete the look. Rejecting gender norms, Baroness Elsa sported a shaved head and often wore men’s clothes. While participation in a protest landed her in jail, the arrest was published in The New York Times with a focus on her crossdressing.

The Demise of The Baroness of Dada

Baroness Elsa was living artwork whose nonconformist views ultimately meant living most of her life in poverty. Having never monetized her art, she never reached financial success and lived a chaotic life fighting sexual politics and social hierarchy. In 1923, she moved back to Europe after relinquishing her New York apartment and spending a month living in the public parks.

She returned to Berlin, hoping to reconnect with the avante-garde art scene. She learned that her father had disinherited her before he died. Destitute, The Baroness sold newspapers. In her desire to move to Paris, she showed up at the French Consulate interview with a birthday cake on her head. She didn’t make it to Paris until 1926, but the move proved to be futile. By the next year, Baroness Elsa was found dead of asphyxiation by gas, along with her pets, in her Rue Barrault apartment.

It was a sad end for The Baroness, whose death remains a mystery, with friends thinking it may have been more of a joke than suicide or an accident — a final punchline in the life of the Dadaist who refused to live — and die — according to societal norms.

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)