I don’t believe in art. I believe in artists. – Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp was one of the artists who challenged long-held beliefs about the art creation process and art itself. Duchamp was a successful painter in Paris in the years leading up to World War I. “I was interested in ideas — not just in aesthetic products,” he said, explaining why he stopped painting nearly altogether.

In search of an alternative to painting objects, Duchamp began presenting familiar items as works of art. He chose mass-produced, commercially available, and frequently utilitarian things to specify as art and assign labels to. He shattered centuries of thinking about the artist’s position as a competent producer of original handcrafted works by coining the term “readymades.” “An everyday item might be raised to the dignity of a work of art by the simple choosing of an artist,” Duchamp claimed.

Rebel, Agent Provocateur, and Master of Subversion

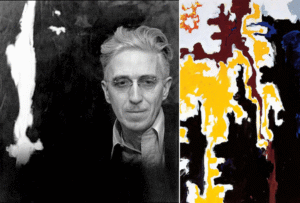

Marcel Duchamp, a French-American painter, sculptor, writer, and chess player was born on July 28, 1887. Duchamp’s works were associated with Cubism, Dada, and conceptual art movements and were often considered as one of the most seminal names in early 20th century art responsible for revolutionary breakthroughs in plastic art, such as painting and sculpture, alongside artists like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse.

Few artists may claim to have altered the path of art history as significantly as Marcel Duchamp. His early readymades generated shock waves across the art world that may still be felt today by questioning the fundamental concept of what constitutes art.

Duchamp’s ongoing interest in the mechanics of desire and human sexuality, as well as his penchant for wordplay, also connects his work with that of the Surrealists, despite his adamant refusal to be associated with any artistic movement. He is often regarded as the founder of conceptual art because of his conviction that art should be motivated by ideas above all else.

Duchamp’s unwillingness to pursue a traditional creative route was equaled only by his fear of repetition, which explains the very modest number of works he made throughout his art career. Duchamp famously spent his last years playing chess, even while he worked on his final cryptic masterwork in secret, which was only revealed after his death.

Readymades – How Conceptual Art Came To Be

Duchamp pioneered two of the most significant breakthroughs of the twentieth century in sculpture: kinetic art and readymade art. These were everyday things that had been slightly changed and labeled by the artist as works of art.

The word “readymade,” coined by Duchamp, referred to mass-produced commonplace things removed from their regular setting and elevated to the rank of artworks solely via the artist’s choosing. The readymade, which was both a performative act and a stylistic term, has far-reaching consequences for what may be called an object of art.

Bicycle Wheel (1913), a wheel placed on a wooden seat, and In Advance of the Broken Arm, a snow shovel, were among his early readymades (1915). One of his early works is also the Readymade Bottle Dryer, created in 1914, was a mass-produced everyday object, regarded by most as a relatively useless object whose shape, when separated from its purpose, had its own distinct feature, but which had previously been hidden in plain sight, until Duchamp’s gesture of signing and the meaning it bestowed. This gesture of Duchamp was later considered the “genesis” of conceptual art.

In 1917, Duchamp purchased a urinal, a urinal basin for public urinals, from the New York sanitary ware retailer “J. L. Mott Iron Works,” gave it the title Fountain, signed it with the pseudonym “R.[ichard] Mutt.” He then submitted it to the Society of Independent Artists’ first annual exhibition in New York under this pseudonymized artist’s name.

Challenging The Notion Of What Is Art

Duchamp purposefully broke all of conventional art’s “rules,” provoking the jury of the show, to which he belonged and from which he resigned in protest after the piece was rejected. Fountain was photographed and then thrown away by Alfred Stieglitz and urinated on by Brian Eno, an artist and musician, at the Museum of Modern Art. Note that it is sometimes credited to the German-born poet and artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven rather than the artist with whom it is most frequently identified. But undoubtedly, it is the most notorious readymade work of art in art history. It inspired various artists from Grayson Perry to Damien Hirst, Richard Hamilton to Richard Wentworth, and many others to ‘interact’ with it in the most visible way in gallery and museum settings.

It was also the most well-known and purposefully controversial of all the readymade things he created. The fact that Duchamp picked the item from the plumbing store rather than fabricating them gave them a quasi-philosophical, iconoclastic edge, which sparked a broad rethinking of art’s conventional standing in the 1950s and 1960s. Within postwar art, the readymade developed their own genre.

This challenge to conventional mediums such as painting, hand-crafted sculpture and their fundamental characteristics, were crucial elements to Duchamp’s legacy in conceptualism. The monumental impacts made by his oeuvre in the last century have been a continuing influence and inspiration to many iconic artists — Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, and Jeff Koons, just to name a few. After all, how can we forget the controversial “banana taped to a wall,” the most recently minted notoriety by the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian without ever thinking of Duchamp?

![Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, 1917, via Wikimedia Commons, [Right] Duchamp smoking in front of Fountain, Duchamp Retrospective, Pasadena Art Museum, 1963](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Marcel-Duchamps-Readymades-Birth-of-20th-Century-Conceptualism-–-Conceptual-Art-Series-Part.-4-768x451.png)