“I paint what I see, not what others like to see.” – Édouard Manet

It can’t be helped. When you first look upon Le Déjeuner Sur L’herbe (1863) by French painter Édouard Manet, your eyes are instinctively drawn towards the woman who illuminates against the darker, rich tones of her background. But it’s not just her flawless fairness that captivates you – it’s the way she directly meets your gaze with an expression that could easily be misinterpreted as inviting. Her discarded clothes and hat lay bundled on the ground beside her. A basket sits on top of her clothing, appearing to have been knocked over as some of its contents have spilled out. Fruits lay on the fallen leaves. A loaf of bread sits on the dirt.

The woman is in the company of two fully-clothed gentlemen involved in conversation. Their postures and positioning of their legs suggest a close companionship. The three sit comfortably in the grass surrounded by lush trees. The man sitting closest to her stares out as if distracted or deep in thought. Behind them is another woman who wears only a chemise as she washes herself in the stream.

The composition is reminiscent of Le Concert Champêtre (The Pastoral Concert) (1510), the oil-on-canvas suspected to be the work of Titian. The way the three main subjects are positioned and posed is also very strikingly similar to the three figures in the bottom right corner The Judgment of Paris, by Marcantonio Raimondi (after Raphael), the black engraving on ivory paper that was published between 1515-1525 – almost as if Manet directly used the characters as references.

The figures in Manet’s painting are based on otherwise ordinary people – the naked woman is one of Manet’s favorite models, the man beside her is his brother, the man facing her is a friend and sculptor. The female bathing in the background is the sculptor’s sister and the woman Manet would marry that same year.

On paper, Le Déjeuner Sur L’herbe reads like any other work of Realism, Impressionism, or Modernism. Focus on the basket of fruit and bread on the ground and it could exist separately as a still life painting. And even the landscape follows the traditional rules of painting. So why would Le Déjeuner Sur L’herbe godown in history as controversial, iconic, and a catalyst for the departure from convention?

Scandal at the Salon

In 1863, Emperor of France Napoleon III ordered the Salon des Refusés, which translates to “Exhibition of the Refused,” to show works by artists who had been rejected by the official Salon’s jury. The Emperor used the event to placate the artists who protested together against the juried art show, which accepted only 2,783 of the over 5,000 paintings. The Salon for “rejected” art provoked such curiosity amongst the Parisians that the event drew seven thousand visitors on its first day. Manet’s work was one of the rejected.

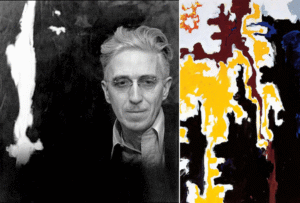

In a letter to French journalist and close friend, Antonin Proust, from a year earlier, Manet stated, “Fine I’ll do them a nude… Then I suppose they’ll really tear me to pieces. They’ll tell me I’m just copying the Italians now, rather than the Spanish. Ah, well, they can say what they like.”

At the time it was first displayed at the event, the painting originally titled Le Bain (The Bath) caused quite the stir. The reaction to Le Déjeuner Sur L’herbe ranged from amusement to disgust and outrage. The painting was struck by a stick on more than one occasion. Men accompanied by their families would rush their wives and young children away from the painting to spare them from looking upon such depravity. Reportedly, those same men would return on their own to ogle at the canvas.

But what made the Manet masterpiece so controversial? Surely, it was not the first time that the people of Paris looked upon a nude painting.

Perhaps what makes Le Déjeuner Sur L’herbe scandalous compared to the likes of similar works like Le Concert Champêtre and The Judgment in Paris is its overall personality and narrative. While all the works portray nudes, Le Déjeuner Sur L’herbe depictsa woman who is relaxed, proud, and confident in her starkness. Seemingly unconcerned by the exposure of her naked body, the woman in the painting casually rests her chin in her left hand. It’s as if she has paused from chatting with the two men to look upon you, their observer, and acknowledge your presence. The scene is void of any sexual tension, leading viewers to presume that the women are prostitutes. Because, surely, the ladies of high society would not behave with such “indecency.”

But look closely at the clothing that has been dropped on the ground. The delicate shades of blues and textured material of the dress suggests fine textiles such as lace and silk. There’s also a hat with a feminine bow – a refined accessory not likely to be worn by a sex worker. The critics of the time would not consider these details because the painting sent a message that was more disturbing than a public display of distinguished men of society frolicking in the outdoors with a naked prostitute. What was more unnerving was the depiction of a woman not only revealing her flesh without shame but also claiming her status as an equal.

The nude female in the painting was inspired by Victorine Meurent, a favorite model of Manet, who posed for many of his paintings, including Olympia (1863), Manet’s masterpiece, also considered scandalous at the 1865 Paris Salon. Meurent was 18 or 19 at the time. She was relatively poor and an aspiring artist herself. Because of the notoriety of Le Déjeuner Sur L’herbe, Meurent would become one of the few models who would be known by name. Some biographers believe that Meurent and Manet collaborated on the concept of Le Déjeuner Sur L’herbe. And that it was Meurent’s influence that led Manet to portray her as a poised and powerful female figure casually enjoying the company of educated and well-dressed modern men.

The Enduring Cultural Impact of the Manet’s Masterpiece

The critics of its time ridiculed Le Déjeuner Sur L’herbe as not only risqué but also lacking in technique. While the scenery showed the companions in a forested grove, there were no appropriate shadows and lights – suggesting that the models posed in a harshly-lit studio or were based on photographs. And if Manet had followed the conventional rules of painting, he would have utilized the illusion of depth and distance and painted the woman bathing in the background in a much smaller size.

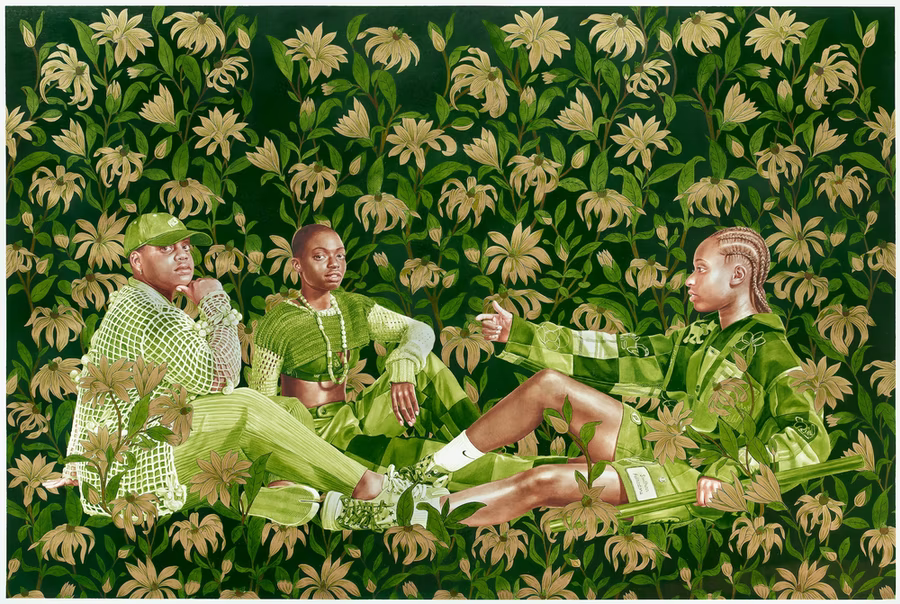

Through the centuries, people have continued to evaluate the motives of the masterpiece while also holding it in high regard – securing its place as a cultural icon. In 1959, it became the inspiration for a movie shot by respected French filmmaker Jean Renoir, “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe.” In 1962, Pablo Picasso paid homage to the Manet painting with Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, after Manet I – Picasso’s interpretation of the masterpiece in his signature Cubism style. In 1979, Robert Colescott reimagined the Manet painting with the satirical Sunday Afternoon with Joaquin Murietta, which replaced the key characters from the original with a Black woman and a legendary bandit. Other artists that have created works inspired by Le déjeuner sur l’herbe include Jeff Koons, Paul McCarthy, Kehinde Wiley, Liu Xiaodong, Cecily Brown, and Dominique Fung.

Many have challenged that Manet was purposeful when he pivoted away from convention. His avant-garde approach to “lazy” brushstrokes, “misuse” of color and light, and distorted depth being intentional. Or maybe it was as Meurent had hoped, a discreet display of feminism that would have been undoubtedly “mansplained” and over-analyzed by the critics.

One of the most significant assessments came from Émile Zola, a respected writer and critic from the late 19th-century Paris’s intellectual circles. Zola described Le Déjeuner Sur L’herbe as Manet’s greatest work of art, “one in which he realizes the dream of all painters: to place figures of natural grandeur in a landscape. We know the power with which he vanquished this difficulty.”