You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think. – Marcus Aurelius

One of the most celebrated portraitists of the 16th century and a master of macabre, Hans Holbein (the Younger) was an artist with an eventful life, to say the least. He traveled Europe extensively, his highly-skilled and versatile art style continually evolved in many different mediums, built an enviable reputation in the English humanist circles, and became King’s Painter in the royal court of Henry VIII.

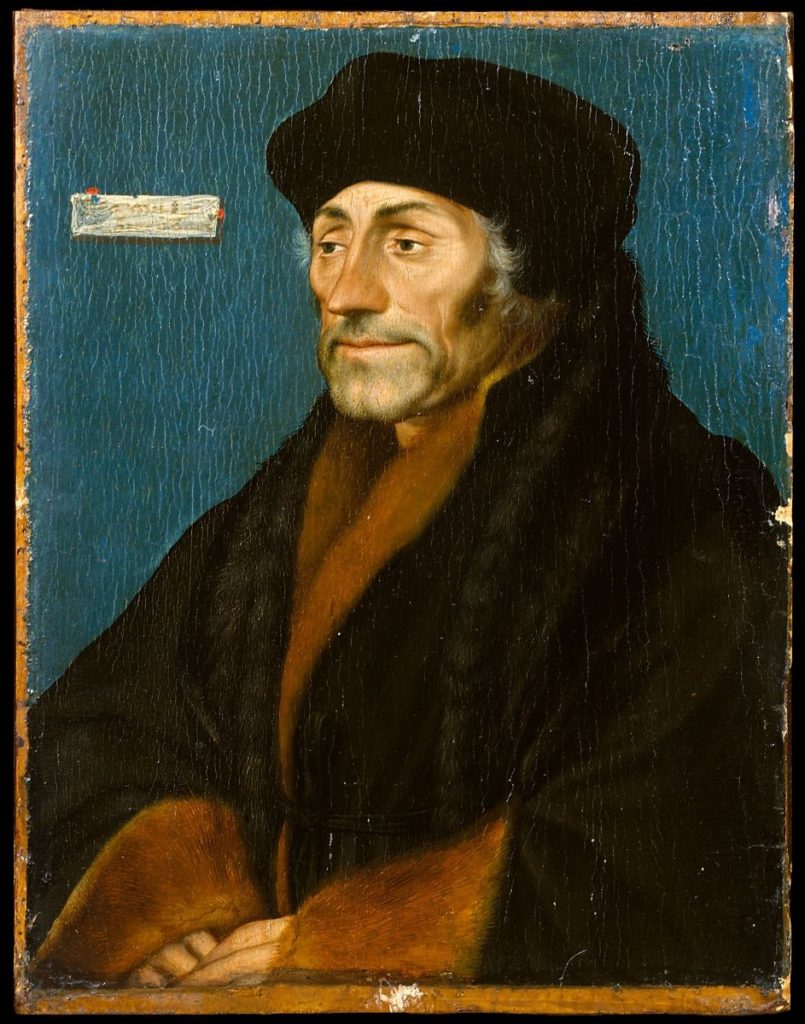

Today, Holbein’s portraits are famous for their technical precision and likeness, the same characteristics that made him renowned during his lifetime. Thanks to him, we know what prominent figures of the 16th century looked like, namely Erasmus of Rotterdam, an influential scholar of the northern Renaissance who recommended Holbein to the powerful English court circle, Thomas More, various dignitaries, and members of the royal family, including Henry VIII and Edward VI as a child. Holbein created a self-portrait as well, which gave us a clear image of an artist that didn’t only possess remarkable skill of rendering a life-form but was unafraid to explore the concept of death in his work.

Early Influences

Born in Augsburg circa 1497, Hans Holbein was taught by his father, Hans Holbein the Elder, who was a painter himself. Holbein the Younger’s early works were influenced by the Late Gothic period and focused on religion, as was the trend at that time. In Basel from 1519 onwards, he painted murals, designed stained glass windows, and worked in book printing.

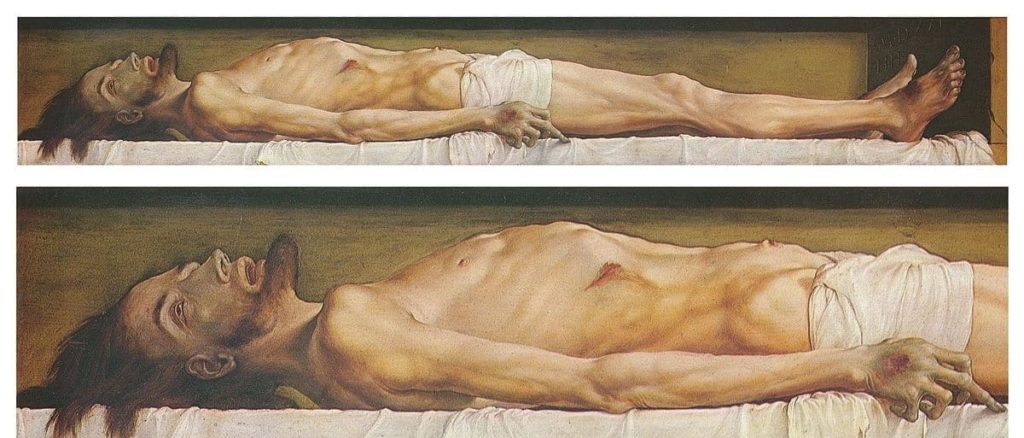

In this period, Holbein created one of his most compelling artworks, The Body of Christ in the Tomb (1520-22). Even though the painting revolves around religion, the depiction of Christ in this manner — in a side view, laid out as though in a coffin, with his unseeing eyes and mouth open — is decidedly humanist. The Christ is wasting away, his wounds from the crucifixion prominent, his feet, hands, and face graying in death. Even Dostoyevsky was so stricken by this sight that he mentioned the artwork in his novel The Idiot, centuries later.

“The face was depicted as though still suffering; as though the body, only just dead, was still almost quivering with agony,” wrote the Russian novelist.

It was clear that Holbein didn’t shy away from grave, disturbing themes even as a young artist.

The Star Of Renaissance

When the Reformation movement reached Basel, Holbein’s art style shifted to incorporate the rising trends in Italy, France, and the Netherlands. He combined Renaissance humanism with his foundation of the Late Gothic style and came away with an aesthetic that was unique only to himself.

In 1526, Holbein traveled to England for the first time, where he met Sir Thomas More. More was already enraptured by Holbein’s skill, having seen his portrait of Erasmus from three years before. It didn’t take long for Holbein’s portraitist career to take off in England, where he returned after a brief stay back in Basel.

During his time in England and at the royal court, Hans Holbein portrayed merchants, landowners, royal visitors, and courtiers. He was bold in adding reminders of mortality, as evident in the painting The Ambassadors (1533). This is a double portrait of Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve, sent by King Francis I of France, who visited England to discuss diplomacy with King Henry VIII.

The two diplomats were showcased in exquisite detail, and yet surrounded by symbolic elements — a lute with a broken string, alluding to disagreement; a book open on a text by Luther, suggesting positive feelings regarding reform. However, the most noticeable symbol is in the foreground — an elongated shape that seems almost as a mistake, an afterthought. When one comes to stand in a particular place from an acute angle of the painting, the elongated shape becomes a skull — anamorphosis perspective. ‘Vanitas’ or ‘Memento mori,’ remember you have to die, reminding viewers we’re all mortals. Even in finely painted details of a rich and vibrant work of art, Holbein was encouraging contemplation of one’s death.

The Dance Of Death

Aside from the stunning portraits that Hans Holbein was known for, one of his most impactful artworks comes from his time spent in the Swiss town of Basel, called The Dance of Death (1523-25). It is a series of woodcuts made in his twenties, in which Death strides into the lives of thirty-four people to brazenly end them. No one is spared; a knight, a physician, members of the clergy, a plowman, an advocate, an astrologer — Death doesn’t choose.

By virtue of Holbein’s keen mind and skills for subtle mastery of integrating his own beliefs and messages into his work, we can make a few assumptions about this outstandingly grim artwork. Death skewers a knight right through his armor; it boldly pulls an abbot by his clothes; breaks a corrupt judge’s staff in two. When it comes to the wealthy class and especially members of the clergy, Death is ruthless.

At the same time, Death takes a gentler route when dealing with the less fortunate. It helps the plowman, taking over the reins of his horses to spare him further labor. When it comes to the poor, death is dealt as a kindness rather than a horrific punishment, as it is to those who have been corrupted by power and money. Not only does The Dance of Death serve as a strong reminder that all that lives must die, but it also emboldens Holbein’s social criticism of the wealthy and the Catholic church.

The Grim Legacy

Holbein died in London between October 7th and November 29th, 1543. According to his biographer, Karel van Mander, he died from the plague, though some sources suggest that it was a different infection that took him.

Others go further and speculate that he was killed by King Henry VIII because he depicted Anne of Cleves as far more beautiful in her portrait than she really was, prompting the King to want to marry her, only to be disappointed when he met her. Perhaps, Holbein fell victim to those who were violently against foreigners in England.

Whatever the case, to this day, no one is certain where Holbein’s remains are. There is no monument and no gravestone to mark his resting place, suggesting that one of the many plague pits in London is the most likely option. Even though the painter had more than enough money to secure himself a funeral and a tomb, he chose not to do that.

In the end, the mystery of Holbein’s death is fitting to the nature of his artworks. He welcomed Death as an old friend, not caring for where his remains ended up. After all, once the time came, it would be the least of everyone’s worries, especially in a time of rampant plague. Sooner or later, even the brightest talent of one’s time can end up in an unmarked grave, dancing with Death, just like in Holbein’s famous woodcuts.

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)