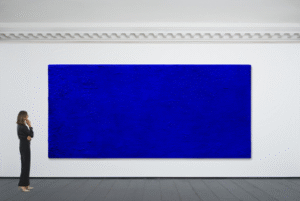

In recent decades, the global art scene has experienced a remarkable transformation, gradually shifting its focus eastward to embrace Korean artists’ understated yet profoundly expressive works. Monochrome painting, or Dansaekhwa, a genre born from Korea’s post-war turmoil, stands at the center of this shift. Now, this deeply Korean artistic movement is gaining widespread international recognition and appreciation, reflecting a broader global focus towards the East.

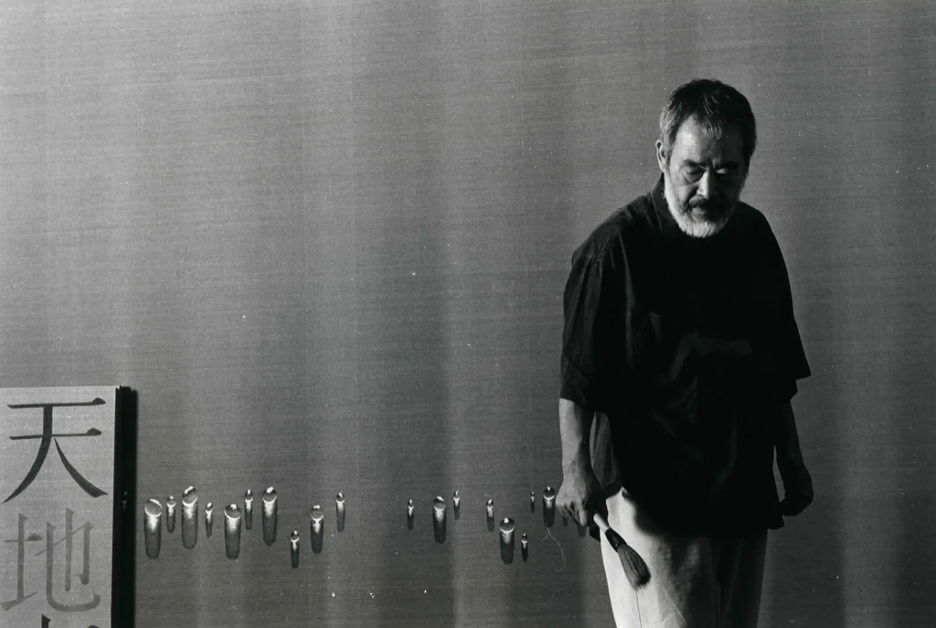

Born amid the sociopolitical upheaval of the 1970s, Dansaekhwa pioneers such as Chung Chang-Sup, Park Seo-Bo, Lee Ufan, Yun Hyong-Keun, Chung Sang-Hwa, and Ha Chong-Hyun sought transcendence through meditative artistic practices that emphasized process over end result. Their creations, distinguished by repetitive gestures and natural materials, speak to a universal yearning for serenity and introspection in chaotic times.

Dansaekhwa’s increasing prominence in the art scene signals a widespread reevaluation of art history, which recognizes the crucial role of non-Western artistic movements. As major exhibitions and prestigious auctions increasingly showcase these Korean masterpieces, it becomes evident that the global art community is not merely looking east but embracing a more inclusive narrative of creative innovation.

Origins of Dansaekhwa: Art Amidst Turmoil

The emergence of Dansaekhwa is inextricably linked to the profound trauma that defined 20th-century Korea. Following Japanese colonization (1910-1945) and the devastating Korean War (1950-1953), artists found themselves navigating a fractured society caught between military dictatorship, rapid industrialization, and an urgent search for national identity.

In this crucible of change, Dansaekhwa artists developed a visual language that responded to their circumstances while deliberately avoiding overt political statements that might trigger government censorship. Instead, they turned inward, creating works characterized by monochromatic palettes, textural explorations, and meditative repetition.

What distinguishes Dansaekhwa from contemporary Western movements is its spiritual foundation. While sharing visual similarities with Minimalism, Dansaekhwa was never about reduction for its own sake, but rather about connecting to deeper philosophical traditions rooted in Eastern thought. This quiet rebellion manifested in works emphasizing materiality and process—Park Seo-Bo’s rhythmic, pencil-traced canvases; Ha Chong-Hyun’s “back pressure” technique of pushing paint through hemp canvas; and Chung Chang-Sup’s incorporation of traditional Korean hanji paper made from mulberry bark.

Joan Kee, author of ‘Contemporary Korean Art: Tansaekhwa and the Urgency of Method’—the first comprehensive English-language study of this movement—notes that artists such as Lee Ufan, Park Seo-Bo, Yun Hyong-Keun, and Ha Chong-Hyun approached overwhelming forces like decolonization and authoritarianism through highly individual expressions. Their work challenged viewers to reconsider how they understood their world rather than why, emphasizing process and material engagement over explicit political messaging.

Note 1: Tansaekhwa and Dansaekhwa are identical terms referring to the same Korean monochromatic art movement, differing only in the romanization style of the Korean word ‘단색화.’

Note 2: In Korea, the family name comes first and is followed by the given name.

Philosophy in Practice: The Meditative Techniques of Dansaekhwa Artists

The methodologies employed by Dansaekhwa artists reflect profound connections to Eastern philosophical traditions, particularly Korean Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. Their repetitive, labor-intensive processes transform the act of creation into a meditative practice—a means of achieving unity with materials and transcending the self.

Park Seo-Bo’s “Ecriture” series exemplifies this philosophy. Park, who passed away in 2023, worked meticulously over countless hours drawing pencil lines into wet oil paint, a process that fostered both discipline and introspection. The resulting works—marked by rhythmic, deliberate impressions—served as records of not just physical labor but spiritual cultivation. “I enter into something akin to a meditative state after emptying everything out,” he reflected, recognizing that “a work of art is not merely an image that sits atop a canvas; it must be self-cultivated and achieved through purification.”

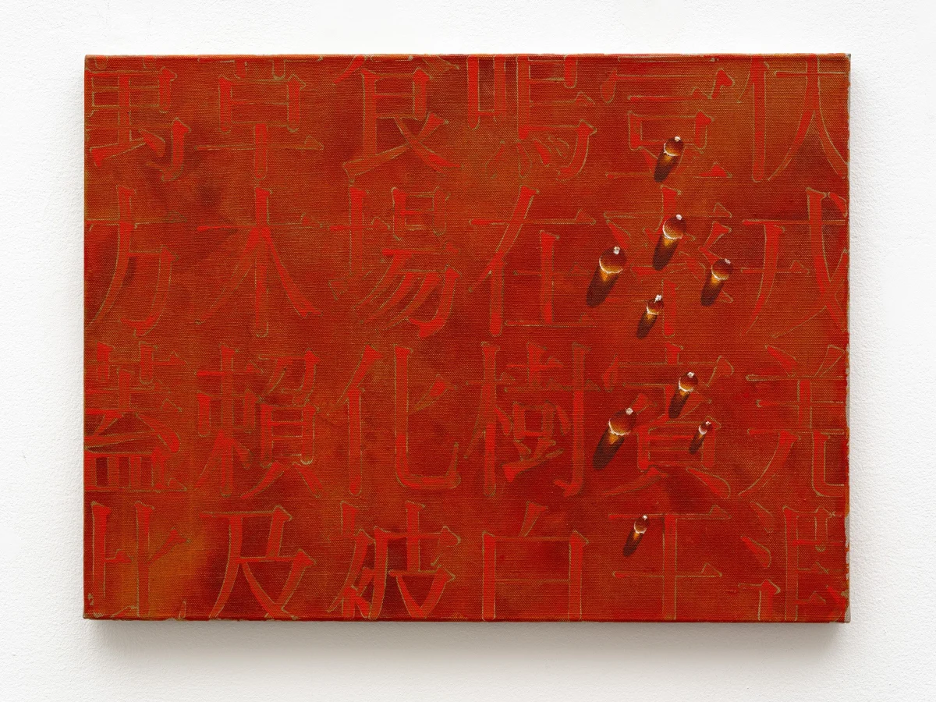

Kim Tschang-Yeul’s iconic “Waterdrop” paintings—depicting hyperrealistic water droplets suspended on abstract backgrounds—draw directly from Taoist principles of letting go. “With water drops as the unique medium, I may see through the surface.” Kim once stated. Each meticulously rendered droplet becomes a metaphor for impermanence and the dissolution of the ego.

For Chung Chang-Sup, materials themselves carried philosophical significance. His incorporation of hanji paper—traditionally used in Korean homes for everything from windows to floor coverings—connected his art to everyday Korean life and ancient traditions. By soaking and manipulating the mulberry fiber, Chung engaged in a dialogue with a material that symbolized Korean cultural identity.

These approaches reveal how Dansaekhwa transcends mere aesthetic choices. The repetitive mark-making, the emphasis on natural materials, and the embrace of chance and materiality all serve a higher purpose—creating spaces for contemplation and spiritual connection in an increasingly industrialized world.

East Meets West: Dansaekhwa’s Dialogue with Global Art Movements

While Dansaekhwa developed within Korea’s specific cultural context, its relationship with Western art movements reveals both fascinating parallels and crucial distinctions. For decades, critics mischaracterized Dansaekhwa as a derivative of American Minimalism or Abstract Expressionism—a misconception that recent scholarship has emphatically corrected.

As gallerist Tina Kim observes, “Many scholars misunderstood Dansaekhwa, which literally translates as ‘monochromic paintings,’ as a Korean interpretation of American Minimalism—the exhibition [at the 2015 Venice Biennale] showed that it was quite the contrary.” The movement emerged not as an imitation but as a conscious act of cultural resistance, with artists actively seeking to create a distinctively Korean visual language.

In reality, Dansaekhwa shares more profound connections with European post-war movements like Gruppo Zero, Lucio Fontana’s Spatialism, and European Informel—all of which questioned the physical and conceptual boundaries of painting. Lee Ufan, who lived in Japan and became associated with the Japanese Mono-ha movement, served as a crucial bridge between East Asian and European artistic discourses.

What distinguishes Dansaekhwa from its Western counterparts is its unique fusion of avant-garde experimentation with Eastern philosophical principles. While American Minimalists like Donald Judd sought to eliminate the artist’s hand entirely, Dansaekhwa artists emphasized the physical trace of their bodily engagement with materials. And unlike the dramatic gestures of Abstract Expressionism, Dansaekhwa’s repetitive actions aimed not at self-expression but self-dissolution.

This complex interplay between Eastern and Western approaches has contributed significantly to Dansaekhwa’s contemporary relevance, offering a third way that transcends the binary of Eastern tradition versus Western modernism.

From Obscurity to Spotlight: Dansaekhwa’s International Resurgence

Dansaekhwa’s journey from relative international obscurity to global recognition represents one of the most remarkable art world narratives of the 21st century. Though the movement flourished in Korea during the 1970s and 1980s, it remained largely unknown to Western audiences until relatively recently.

The turning point came in 2015, with the “Dansaekhwa In Venice” exhibition as part of the official collateral events of the 56th Venice Biennale, curated by Yongwoo Lee and organized with Kukje Gallery, Seoul, and Tina Kim Gallery, New York. This landmark exhibition, featuring works by key figures including Park Seo-Bo, Ha Chong-Hyun, and Lee Ufan, introduced the movement to international audiences in unprecedented fashion and catalyzed a meteoric rise in market appreciation and scholarly attention.

The exhibition showed that Dansaekhwa was born from a distinct historical context in South Korea, which at the time was still under dictatorship and recovering from the Korean War, Kim explains in an interview with The Observer. By recontextualizing these works, the exhibition revealed how Dansaekhwa artists were “expressing their frustration with the oppressive government censorship of the ’70s and ’80s” while simultaneously developing a uniquely Korean artistic language.

This renewed understanding has led to a cascade of major institutional exhibitions. Museums like the Guggenheim, MoMA, and Centre Pompidou have acquired significant Dansaekhwa works, while commercial galleries from New York to London have mounted influential shows. The 2018 exhibition “Dansaekhwa and Korean Abstraction” at the Barakat Gallery in London, for instance, further cemented the movement’s place in global art discourse.

Most recently, Tina Kim Gallery in New York organized “The Making of Modern Korean Art: The Letters of Kim Tschang-Yeul, Kim Whanki, Lee Ufan and Park Seo-Bo, 1961–1982,” offering unprecedented insight into the intellectual and personal relationships that shaped modern Korean art. The exhibition, which runs through June 21, 2025, features key works alongside rare archival materials and correspondence, tracing how these artists developed abstraction as a response to national trauma and as a means of forging a distinctive cultural identity.

Redefining Modernism: Dansaekhwa’s Place in Contemporary Art History

The global recognition of Dansaekhwa has precipitated a profound reassessment of art historical narratives, challenging the long-dominant Western-centric view of modernism. As art historian Joan Kee argues in her seminal text “Contemporary Korean Art: Tansaekhwa and the Urgency of Method,” these artists were not late adopters of Western modernism but creators of a parallel modernist trajectory with its own internal logic and philosophical underpinnings.

This reconsideration has broader implications for how we understand global art movements. It undermines the simplistic notion that artistic innovation flows unidirectionally from West to East, instead revealing a complex network of influences, exchanges, and parallel developments.

The 1980s marked a critical juncture in this evolving narrative. During this period of rapid economic growth in South Korea, driven by post-dictatorship modernization efforts after 1979, the government recognized the cultural and diplomatic potential of the arts to enhance the country’s global profile. As the 1988 Seoul Olympics approached, Korean art gained unprecedented international visibility, coinciding with the rise of influential institutions like Kukje Gallery that would help shape the Korean art ecosystem.

In the decades since, South Korea’s creative industries—especially its pop culture—have fueled a global surge in visibility. The so-called “Korean Wave (Hallyu)” has extended well beyond K-pop and K-dramas to encompass contemporary Korean art, which has increasingly captured international attention and acclaim.

The Market’s Embrace: Dansaekhwa’s Economic and Cultural Impact

The commercial trajectory of Dansaekhwa tells a compelling story about shifting values in the global art market. While these works were created with profound philosophical intent rather than commercial ambition, they have nonetheless experienced extraordinary market appreciation over the past decade.

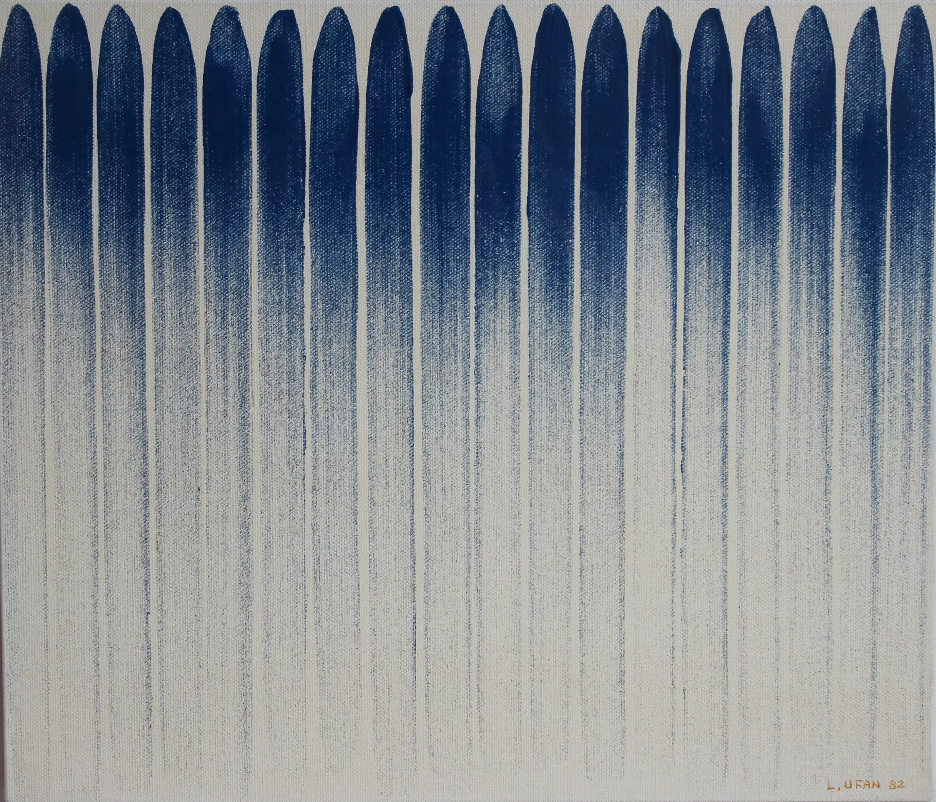

Works by Dansaekhwa masters that might have sold for tens of thousands of dollars in the early 2000s now regularly command millions at international auctions. Park Seo-Bo’s Écriture No. 3-82 (1982) experienced a remarkable increase in value, selling for $56,750 in November 2013 and reselling for $631,972 in May 2015, reflecting a more than tenfold appreciation in less than two years. His auction records have continued to rise, with works fetching up to HK$20.4 million (approximately US$2.6 million) in recent years.

Lee Ufan’s painting East Winds sold for approximately 2 billion won (about US$1.7 million) at a Hong Kong auction in October 2019. The same work resold for 3.1 billion won (around US$2.6 million) in 2021, marking the highest auction price for a living South Korean artist. Ha Chong-Hyun’s Conjunction 2002-24 sold for HK$1,120,000 (approximately US$144,000) at Christie’s in May 2015. His works have continued to appreciate, with pieces like Conjunction 90-002 achieving HK$945,000 (about US$121,000) at Phillips.

In November 2019, Kim Whan-ki’s monumental diptych 05-IV-71 #200 (Universe) (1971) sold for HK$101,955,000 (approximately US$13.1 million) at Christie’s Hong Kong, setting a record for the highest price achieved by a Korean artist at auction.

This market surge reflects broader economic and cultural factors. South Korea’s emergence as a global cultural powerhouse has enhanced the visibility and desirability of its artistic heritage. Meanwhile, collectors increasingly seek to diversify their holdings beyond the traditional Western canon, recognizing both the aesthetic value and investment potential of previously underappreciated non-Western movements.

Legacy and Influence: Dansaekhwa’s Role in Shaping Future Artists

The enduring significance of Dansaekhwa extends far beyond the art market, shaping the trajectory of contemporary art both within Korea and around the world. With its emphasis on materiality, process, and philosophical inquiry, the movement offers a thoughtful counterpoint to the conceptualism and spectacle that often dominate global contemporary practice.

Young Korean artists such as Haegue Yang, Do Ho Suh, and Lee Bul, though working in distinctly modern idioms, openly acknowledge the foundational impact of Dansaekhwa. Their internationally acclaimed work builds upon the path forged by these pioneers, even as they explore new media and engage with pressing social and cultural issues of the present.

The influence of Dansaekhwa has also extended well beyond Korea. Artists from a variety of cultural backgrounds have drawn inspiration from its meditative techniques, repetitive gestures, and attention to material process. In an era increasingly defined by digital acceleration, such practices resonate deeply with global concerns around mindfulness, sustainability, and the search for slower, more intentional modes of creation.

This global rise of Korean art has been supported by strategic investments from the Korean government in cultural infrastructure. Institutions like the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) and the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art provide world-class platforms for showcasing both established and emerging artists. At the same time, private foundations and corporate patrons have amplified these efforts through ambitious exhibitions and acquisition programs that elevate Korean artists on the global stage.

Within the quiet intensity of Dansaekhwa’s monochromatic surfaces, viewers are invited to slow down, look more closely, and contemplate the profound threads that link artistic traditions across time and geography. In a world marked by fragmentation and distraction, that is a vision worth holding onto.

As gallerist Tina Kim notes, “Today, K-pop and K-drama are popular worldwide, and Korean art, of course, is benefiting from this widespread interest in Korean culture.” This cultural synergy—between the mass appeal of Korean entertainment and the contemplative rigor of its fine art—has opened unprecedented opportunities for Korean artists and institutions around the globe.