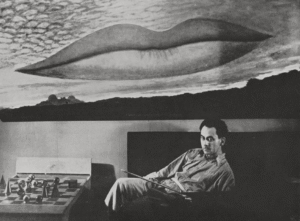

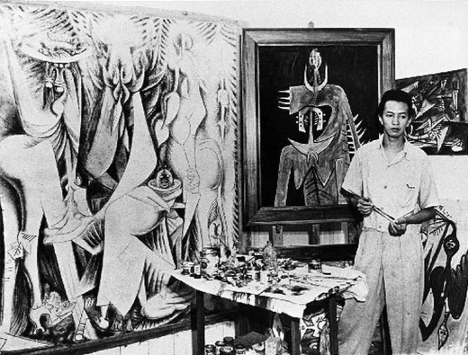

There are moments in the life of museums when an exhibition does more than bring together a celebrated body of work; it shifts an axis. Wifredo Lam: When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream at the Museum of Modern Art reminds us that modernism was never a monolith — and that the imagination, when rooted in identity and resistance, can truly reshape history. As When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream brings his vision into focus, it’s more than a retrospective: it’s a reckoning.

For years, Lam’s name appeared in conversations about Surrealism, cubist experimentation, and Caribbean visual culture, yet the precision of his artistic project — and the radical nature of his imagination — was often blurred by categories too narrow to hold him. This exhibition refuses those inherited limitations. Instead, it positions Lam as a visionary who understood early on that modernism was not a Western phenomenon to be imitated, but a global terrain demanding reinvention.

Born in Cuba to African and Chinese ancestry, Lam carried within him multiple cosmologies, histories, and cultural vocabularies. His years in Europe honed his discipline; his return to the Caribbean ignited his imagination. In that return — after nearly two decades abroad — his work found its singular force: a visual language capable of bearing the weight of spiritual knowledge, political resistance, and mythic memory. Lam once described his art as an “act of decolonization” — a phrase that today feels both prescient and deeply resonant. His paintings were not simply pictures to be decoded, but propositions about how to see a world fractured by empire yet rich with ancestral presence.

A Modernism Reimagined

Lam’s path into the modernist avant-garde was never linear. In the 1930s, Europe provided him with formal tools and philosophical urgency: the collapse of old orders, the rise of fascism, and an artistic community wrestling with the inadequacies of tradition. But his true rupture came later, when he returned to Cuba and met again the spiritual rhythms, ceremonial spaces, and cultural ecosystems that had shaped his earliest memories.

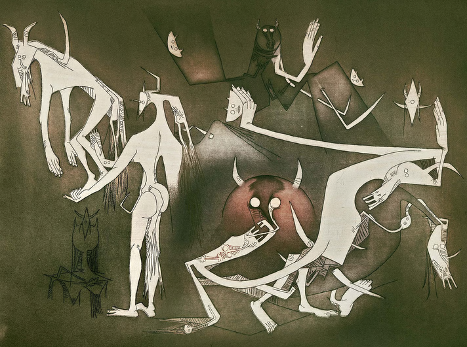

The paintings that emerged from this period — dense with hybrid forms, vegetal spirits, shadowy lineages — did not simply merge European modernist strategies with Afro-Caribbean cosmologies. They unsettled both. Lam’s figures appear suspended between worlds, charged with energies that refuse containment. They are at once human, animal, botanical, and divine; embodiments of histories that official narratives tried to suppress.

What MoMA’s retrospective illuminates so clearly is that Lam understood art not as a stylistic exercise but as a terrain of liberation. His figures dissolve the boundaries between body and spirit, landscape and psyche, past and present. The paintings ask us to look not at what is represented but at what is summoned.

Dreaming in the Hours of Wakefulness

The exhibition title “When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream” captures a central truth about Lam: his imagination never rested. Whether in wartime Europe or the charged tropical atmospheres of the Caribbean, he remained alert to those liminal spaces where memory and myth converge.

The galleries at MoMA trace the arc of this restless vision: early portraits echoing the rigor of European classicism; wartime works marked by tension and dislocation; the explosive hybrid imagery of the 1940s; the expansive, abstracted forms of his later decades. Seen together, the works reveal an artist whose evolution was not a series of stylistic pivots but an ongoing conversation with history — his own, and that of the world around him.

Lam considered his paintings to be invitations rather than explanations. He once admitted he might not be understood immediately, yet trusted that “true images have the power to set the imagination to work.” The exhibition honors that trust, allowing each work to unfold as a dream that continues long after the viewer walks away.

Art Market Currents: A Recognition Long in Waiting

The art market has slowly begun to align itself with what scholars and artists have known for decades: Lam’s work occupies a critical, foundational place in the story of global modernism.

It is telling that some of the most significant shifts in his market visibility have occurred in the last decade, mirroring the broader institutional reassessment of artists shaped by colonial histories and diasporic worlds. As museums deepen their commitment to rewriting the canon, collectors have followed — drawn to the blend of intellectual depth, spiritual force, and historical importance that Lam’s work embodies.

The market’s awakening has not been marked by sudden spectacle but by a steady rise in appreciation. One of the most significant moments came in 2020, when Omi Obini, a luminous 1943 canvas — achieved $9.6 million, a record that crystallized the seriousness with which collectors now approach Lam’s mid-century works. This surpassed the previous record set in 2017 for À Trois Centimètres de la Terre(1962), itself a testament to the increasing recognition of Lam’s postwar oeuvre.

More revealing, perhaps, is the attention given to works outside the expected periods of demand. In 2025, an early portrait, Personnage No. 2 from 1939, painted before Lam returned to Cuba and before the emergence of his hybrid mythic language, fetched an impressive $266,700. The result suggested a market no longer content to prize only the “iconic” Lam, but interested in the full complexity of his evolution. Even works from his later decades, such as a 1969 untitled canvas sold in London in 2023, have drawn international collectors into conversation with a broader, more nuanced vision of his legacy.

These sales form not just a record of financial value but a landscape of cultural acknowledgment: a world finally ready to understand what Lam gave to modernism — and what modernism had long overlooked.

Why Lam Matters Now

What makes Lam so compelling today is not only the beauty of his imagery, but the clarity of his proposition: that art can hold the contradictions of identity, history, and spirituality without resolving them; that the modern world, fractured as it is, still offers pathways toward wholeness.

For artists, Lam is a reminder that innovation need not sever ties to ancestry. For curators, he is a guide through the labyrinth of the canon — tracing the lines that were always there but seldom followed. For collectors, he represents a confluence of significance and rarity. And for art lovers, he offers an encounter with painting as a living form of thought.

Lam’s legacy extends far beyond the works themselves. It lives in the artists who draw upon ritual and myth to challenge contemporary structures of power; in the curatorial frameworks that rethink modernism as a global exchange; in the viewers who recognize in his paintings the enduring struggle for liberation — not only from political systems, but from the narrowness of inherited vision.

Looking Forward

When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream is more than a retrospective. It is an invitation to reconsider the narratives that shaped the 20th century — and the ones still shaping our present. Lam’s art carries the force of a dream dreamt awake: charged, lucid, and unafraid to cross the thresholds that separate histories, cultures, and worlds.

In returning to Lam, we are returning to a modernism that was always larger, more hybrid, more luminous than the textbooks allowed. His visions remain urgent not because they belong to the past, but because they continue to reimagine the future, especially when we, too, are not yet fully awake to the histories they contain.