Influenced by earlier art movements such as Spatialism and Dau al Set, the avant-garde Arte Povera movement originated in Italy — lasting a relatively short period between the late 1960s and early 1970s. The radical movement challenged the traditional art world by rejecting fine art materials like oil paint and marble and choosing instead to experiment with a wide range of nonconventional materials. Refusing American Modernism and echoing post-Minimalism, artists who identified with Arte Povera ideals broke away from the norms to juxtapose the new with the old and achieve aesthetics that combined natural elements with the labor and interactions of man. The movement aimed to deviate from abstract art, which was perceived to dominate the art world at the time.

The Interactions of Mundane Materials with the Processes of Perception

Arte Povera literally translates to “poor art,” a term introduced by Germano Celant in 1967 at an exhibition called Im Spazio (The Space of Thoughts). Celant was an influential art critic, curator, and art historian who coined the term after mounting an exhibition of young Italian artists who made assemblages out of unconventional, mundane materials such as coffee grounds, fallen leaves, melted wax, and rusty iron. Celant, who embraced the sentiment, did not mean to diminish the work by categorizing it as “poor” or “impoverished” but rather celebrated the mischievous subversion and rebellious juxtapositions.

Im Spazio would become known as the birthplace of the Arte Povera movement, featuring works by Alighiero Boetti, Luciano Fabro, and Jannis Kounellis — Italian artists hailing from Turin, Milan, and Rome. Boetti’s Mazzo di tubi, Collina was a prominent work from his Arte Povera period and consisted of metal tubes. Fabro also experimented with steel tubes, creating several installations that encouraged interactions between the found objects and the element of space. Kounellis would become known as a forefather of the Arte Povera movement, starting with materials like rope, raw wool, and wood. But Kounellis would evolve past unconventional materials and pushed Arte Povera principles as he transformed gallery spaces into stages for real life interactions, such as his use of live birds in cages in 1967 and twelve living horses in 1969. Kounellis would go on to introduce new materials to his installations, including meat, coal, propane torches, and smoke.

Other key figures with the Arte Povera movement include Mario Merz, Marisa Merz, Pino Pascali, Giovanni Anselmo, Enrico Castellani, Giulio Paolini, Giuseppe Penone, Gilberto Zorio, Emilio Prini, and Paolo Calzolari.

In his 1969 book, “Arte Povera,” Celant would write an introduction for each of the Arte Povera artists he had collaborated with, stating that each “has chosen to live within direct experience” and “feels the necessity of leaving intact the value of the existence of things.” Throughout his 50-year career, Celant continued to nurture the Arte Povera spirit and champion its artists, many of which went on to achieve international acclaim. The art world lost Celant in early 2020 due to complications of the coronavirus.

The Arte Povera movement and its fusion of conceptual art, assemblage, and performance art would acquire other names through the years, including “anti-form” and “actual art” — influencing the rise of other art styles and movements. In Japan, Mono-ha (School of Things) emerged on the heels of Arte Povera with artists rejecting traditional ideas and challenging Japan’s industrialization. And in the U.S., anti-form concepts came into prominence in the late 1960s, paving paths for sculptors to stray from traditional fine art materials and use industrial and organic substances.

The Ambitious Art Hub Asserting Arte Povera

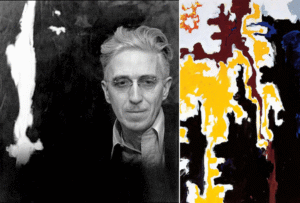

To practice processes that challenge methodical approaches to art, Arte Povera artists rejected the constraints of traditional painting. As part of the movement’s mission to assert the value of common materials and fight what was seen as elitism, artists used common objects as the basis for assemblages. Curiously and perhaps coincidentally, “merz” is the nonsense word invented by German dada artist Kurt Schwitters to describe his assemblage work in 1919 — years before the birth of Mario Merz and decades before Mario and Marisa Merz became pioneering figures in the Arte Povera movement.

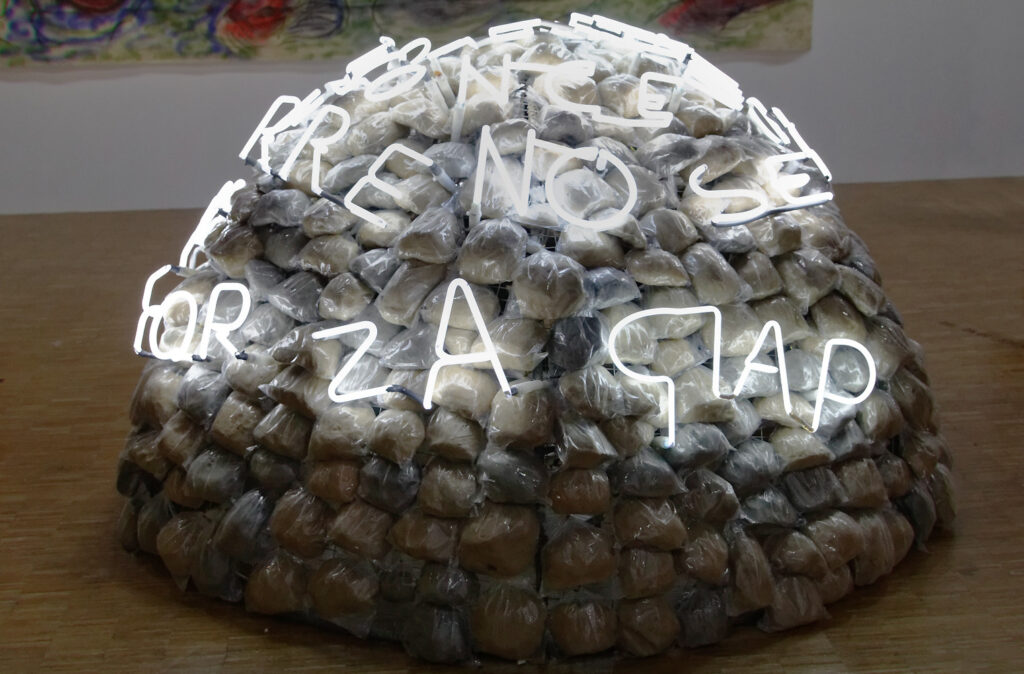

Established in 2005, the Turin-based Merz Foundation, which houses the collection of artworks by Arte Povera master Mario Merz, aims to recognize the talents in the realm of contemporary art. Mario Merz pursued open-ended installations, employing materials like wax, tar, twigs, and fruits – placing them with neon tubes that often spelled out political precepts to create a sense of performance. Mario’s intentions were to create immediate experiences with the art by connecting the viewer to nature.

In its latest endeavor, the foundation expands its growing presence with the opening of ZACentrale in Palermo’s former industrial area known as Cantieri Culturali alla Zisa. Finding its home in a converted factory building, the ZACentrale’s inaugural exhibition L’altro, lo stesso (‘The other, the same’) describes itself as a “cultural adventure.” Palermo was an obvious choice, having been named the European Capital of Culture with its rich ancient history as a crossroads for European, Middle Eastern, and African cultures.

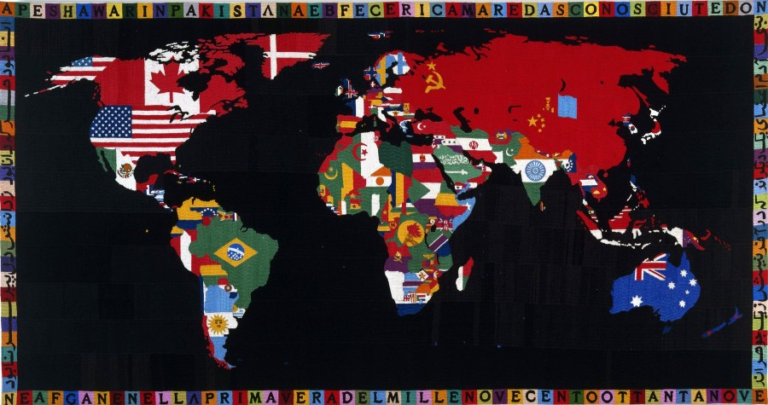

L’altro, lo stesso aims to catalyze the area’s birth as a thriving art hub for contemporary art. With its focus on “the world of theater, music, and poetry” and their impacts on contemporary art, the Merz Foundation stands firmly on its Arte Povera roots. The art space will feature two massive helix installations by Mario Merz. At the center of the exhibition is Mario’s Pietra serena sedimentata depositata e schiacciata dal proprio peso, così che tutto quello che è in basso va in alto e tutto quello che è in alto va in basso, soprelevazione e opera incerta di pietra serena (‘Pietra serena sedimented and crushed by its own weight, so that everything below goes above and everything above goes below, a raising and uncertain work of pietra serena’).

And while the male-dominated Arte Povera movement mostly excluded Marisa Merz from exhibitions, she would become recognized as the sole female presence and leading artist of the movement. Asserting a distinctly feminine spirit through her choice of materials, Marisa unapologetically referenced domestic life and motherhood, using crafts like knitting and braiding. Marisa was often overshadowed by her husband Mario and was eventually celebrated for bringing a uniquely feminine touch to the movement. Marisa’s never-before-displayed works joins 12 other artists at L’altro, lo stesso, including international artists Lawrence Weiner, Rosa Barba, Lida Abdul, and Alfredo Jaar. The exhibition will be held until March 26th, 2022.

Alfredo Jaar’s Two or three things I know about monsters (2016) is installed on the exterior of ZACentrale, an ominous neon sign that quotes Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci: il vecchio mondo sta morendo. Quello nuovo tarda a comparire. E in questo chiaroscuro nascono i mostri.

‘The old world is dying. The new one is slow to appear. And in this twilight monsters are born‘.