On view until September 14, 2025, the Clyfford Still Museum’s current exhibition, ‘Held Impermanence,’ guest-curated by Katherine Simóne Reynolds, draws deeply upon the collections and archives of the museum to explore a fascinating paradox: Still’s fierce desire for artistic control set against the inevitable aging and deterioration of his materials. The exhibition illuminates this tension between preservation and natural transformation, offering a fresh perspective on Still’s work and examining how art evolves over time.

Reynolds has brilliantly and boldly chosen to display pieces that bear visible marks of aging—paintings with condition issues that conservators might call “inherent vice.” These works reveal a vulnerability rarely associated with the famously uncompromising artist.

Some of Still’s works on paper hang behind protective curtains, which visitors may carefully lift for an intimate viewing experience. This thoughtful arrangement gives us a privileged peek, inviting us to consider not just Still’s artistic vision, but the physical reality of his creations as objects that breathe, age, and transform—much like their creator did throughout his remarkable career. While Still worked alongside celebrated Abstract Expressionists like Pollock, Rothko, and de Kooning, his reputation has followed a different trajectory. What qualities make Still’s powerful canvases uniquely his own, and why are audiences today increasingincreasingly drawn to the distinctive vision that set him apart from his more famous contemporaries?

Aesthetic and Philosophical Differences

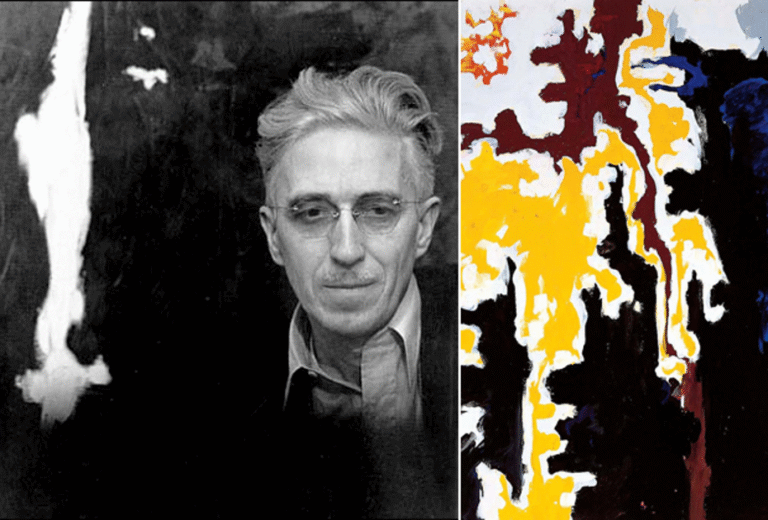

Born in 1904 in North Dakota, Clyfford Still spent his formative years in the expansive landscapes of Washington state and Alberta, Canada. Unlike many of his contemporaries who gravitated towards European influences, Still’s aesthetics were distinctly American—with the vast wheat fields and rugged terrain of the Northwest shaping both his character and his artistic sensibility.

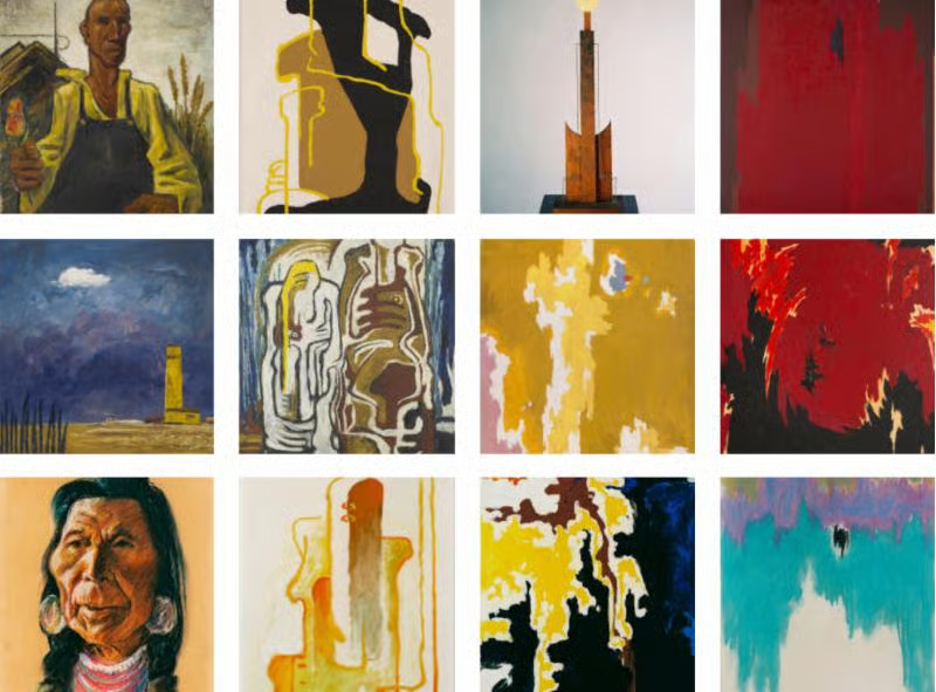

Still began his artistic journey with relatively traditional landscapes and figurative paintings. His early works, created during the Great Depression, often depicted farm laborers with angular, elongated bodies—foreshadowing the jagged forms that would later define his abstract style. While teaching at Washington State College in the 1930s, Still quietly began his transition toward abstraction, a path he would follow with singular determination.

“I never wanted color to be color,” Still once wrote. “I never wanted texture to be texture, or images to become shapes. I wanted them all to fuse into a living spirit.”

The Isolationist of Abstract Expressionism

By the mid-1940s, Still had developed his signature style—monumental canvases with dramatic vertical forms suggesting fissures or flames, rendered in stark contrasts of color. What separated Still from his fellow Abstract Expressionists—Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning—wasn’t just his visual language but his fierce independence.

While the New York School gathered at the Cedar Tavern to debate art theory, Still largely kept to himself. He participated in important group exhibitions at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery and later at Betty Parsons Gallery, but even as his reputation grew, he remained suspicious of the art establishment. In 1950, he abandoned New York for rural Maryland, a self-imposed exile that would define the remainder of his career. This strategic withdrawal would significantly impact the availability of his works to come.

“I’m not interested in illustrating my time,” Still declared. “A man’s ‘time’ limits him, it does not truly liberate him.”

The Aesthetic and Art of Refusal

Still’s canvases are immediately recognizable—vast territories of color punctuated by jagged, vertical forms that seem to tear through the picture plane. Unlike Rothko’s contemplative color fields or Pollock’s energetic splatters, Still’s paintings suggest geological forces and unleashed primal energies—earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

His technique was as distinctive as his vision. Still applied paint with palette knives, creating thick textural depth and strategically leaving portions of canvas raw and exposed. His color palette choices—often deep blacks contrasted with fiery reds, yellows, and occasional blues—create a visual impact of visceral tension. There’s nothing gentle or seductive about a Still canvas; they confront and challenge.

Still’s deliberate choice to avoid descriptive titles for his works stands as one of his most intriguing artistic decisions; instead, he implemented a methodical cataloging system that identified works simply by year and letter. This rejection of conventional artwork titling reflects his belief that his paintings communicated directly, without the need for verbal mediation.

Calculated Distancing and Strategic Scarcity

Still’s most famous act might be his withdrawal from the commercial art world. By the late 1950s, he had severed relationships with galleries and museums he felt were compromising his vision. He refused to sell to collectors he didn’t approve of and declined invitations to major exhibitions. When the Museum of Modern Art organized the landmark “New American Painting” exhibition that toured Europe in 1958-59, Still was the only major Abstract Expressionist to decline participation.

While Still’s massive canvases command attention, his personal life remains enigmatic. Few know that he was an avid letter writer, maintaining extensive correspondence despite his reclusive reputation. His archive contains thousands of letters, including a letter where he describes a night out drinking with Pollock, that reveal a man far more engaged with the world than his public persona suggested.

Still was also fascinated by music, particularly jazz. He maintained a substantial record collection, with a special affinity for the improvisational work of Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk—artists whose creative approach paralleled his visual expression and structured freedom.

Surprisingly, Still maintained a deep interest in teaching despite his character. Before withdrawing from public life, he taught at the Richmond Professional Institute, the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute), and briefly at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

This carefully managed reclusiveness made Still’s paintings increasingly rare and mythic. Unlike Rothko or de Kooning, whose works appeared regularly at auctions and galleries, Still’s paintings were seldom seen and became almost unobtainable. He preferred to keep his work together, believing each painting was part of a larger whole. This decision ultimately led to his bequest of approximately 95% of his lifetime output to an American city willing to create a dedicated museum—a gift that would eventually go to Denver.

The Still Museum: Exclusivity Institutionalized and a Vision Fulfilled

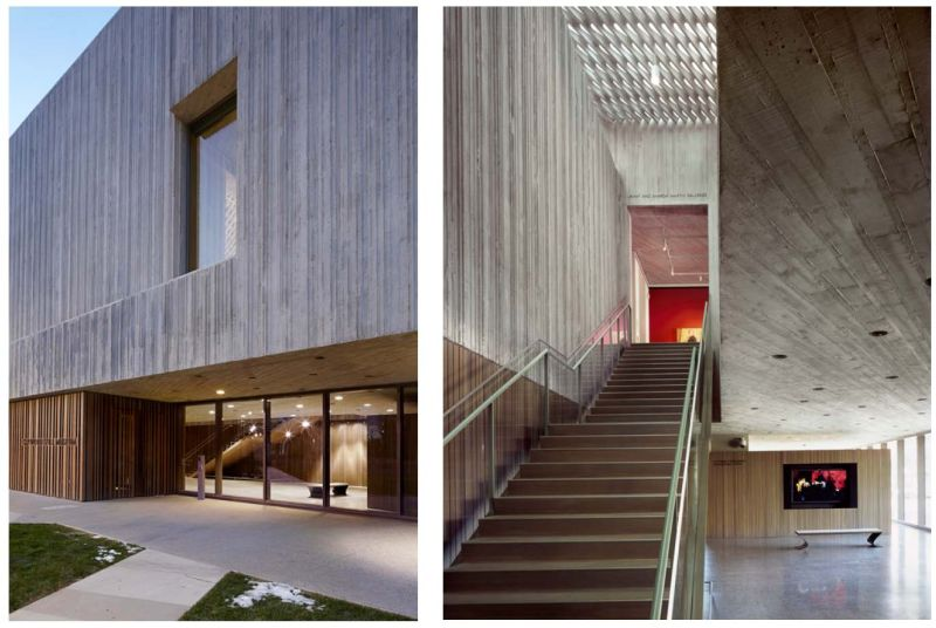

The Clyfford Still Museum, which opened in 2011, houses nearly 3,125 works—representing about 93% of Still’s lifetime output. This unprecedented concentration of a single artist’s work offers visitors something rare: the chance to trace and understand the complete evolution of a major artist’s vision.

Unlike his contemporaries, whose works are scattered across global collections, Still’s corpus remains largely intact, just as he wished. The museum itself—a modernist concrete structure designed by Brad Cloepfil—complements Still’s aesthetic: refined, powerful, and unapologetic.

Today, as Reynolds’ exhibition “Held Impermanence” invites us to see the vulnerability beneath Still’s monumental vision, we’re reminded of the paradox at the heart of his legacy. By refusing to participate in the art world’s exhibition and commerce systems, Still ensured his work would be seen on his terms alone.

The Clyfford Still Museum stands as a vindication of his vision and his defiance. In a cultural landscape where artists increasingly function as brands, Still’s uncompromising stance offers an alternative model—the artist as prophet rather than professional, creating not for markets or critics, but for the sake of an uncompromising, inner necessity. As visitors move through the museum’s thoughtfully sequenced galleries, they experience not just the evolution of an artist; but encounter a vision so singular that it continues to challenge our understanding of what art can be and do in the world.

Considering the present landscape of art, heavily shaped by market-driven commodification and social media influence, what lasting insights and wisdom can contemporary artists gain from Clyfford Still’s unwavering commitment to his artistic principles and his resolute rejection of compromising his creative vision for commercial success?