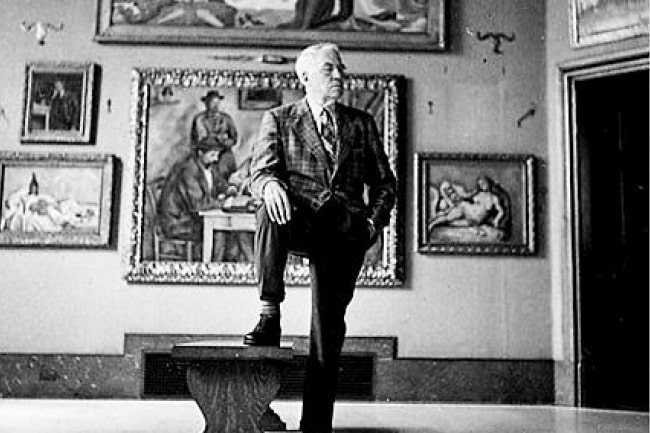

Born to a working-class family, Albert C. Barnes was an American chemist and self-made millionaire. Barnes made his fortune as the co-developer of Argyrol in 1899, an antiseptic compound, consisting of silver and a protein, used to treat gonorrhea infections. In 1902, Barnes and co-creator of Argyrol, German chemist Hermann Hille, organized the partnership of Barnes and Hille. And in 1929, Zonite Corporation bought Barnes’ business – mere months before the stock market crash of 1929, which spiraled into the Great Depression.

As Barnes’ company prospered and he benefited financially, Barnes was able to explore other interests, particularly in the arts and education. He started collecting pieces in the early 1900s, and in 1911, Barnes reconnected with his high school friend William Glackens, who would later become a realist painter and founder of the Ashcan School of American art. Glackens became one of Barnes’ early advisors in art collection and even sent him to Paris to purchase paintings for him.

By 1912, Barnes, who had just turned 40, was already considered a serious art collector as he’d acquired dozens of artwork that cost about $20,000 in total (worth over a half million today). On the heels of Glackens’ buying campaign, which included Van Gogh’s The Postman and Picasso’s Young WomanHolding a Cigarette, Barnes also traveled to Paris where he purchased his first two paintings by Henri Matisse from Gertrude Stein, a leading art collector of modernism and a host of Paris Salon.

“Living with and studying good paintings offers greater interest, variety, and satisfaction than any other pleasure known to man.” – Albert C. Barnes

The Promotion of Education and Art Appreciation

In 1922, Barnes purchased a 12-acre arboretum in Merion, Pennsylvania. Barnes founded the Barnes Foundation, which received its charter from the state as an educational institution. The building was completed by 1925, with the design and construction led by renowned French architect Paul Philippe Cret.

The fate of Barnes’ prized art collection was decided well before his death. However, when Barnes died in a tragic automobile accident in 1951, the Barnes Foundation began to unravel as those left in charge struggled to abide by Barnes’ many stipulations – one of which was the strict prohibition of moving any of the art outside the foundation’s home in the private gallery in Merion, PA.

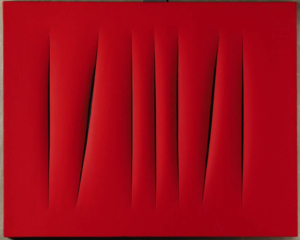

The private collection in the Barnes Foundation was the world’s largest and finest collection of post-impressionist and modern art. It includes: “181 Renoirs, 69 Cezannes, 59 Matisses, 46 Picassos, 16 Modiglianis and seven Van Goghs.” In addition to the magnitude of the collection itself, unique conditions stipulated by Barnes’eccentric tastes in display insisted that “the paintings be hung densely amid medieval relics, African art and modernist furniture.” And “nothing from the collection should be lent, sold or moved on the walls and remain exactly as it was” in the original location. Furthermore, he forbade “any society functions commonly designated receptions, tea parties, dinners, banquets, dances, musicales or similar affairs” where the art would be exhibited. His trust also stipulated that the Barnes Foundation would remain educational, with the collection to be open to the public only a few days a week.

“Appreciation of works of art requires organized effort and systematic study. Art appreciation can no more be absorbed by aimless wandering galleries than can surgery be learned by casual visits to a hospital.” – Albert C. Barnes

The Barnes Foundation Relocation Battle

When the foundation’s board announced on September of 2002, the plan to relocate Barnes’ massive art collection from Merion to a museum in downtown Philadelphia, forces who felt they were dishonoring Barnes’ wishes for financial gain pushed back hard. What resulted was a court battle that lasted years between activists and those they accused to be driven by greed.

“The main function of the museum has been to serve as a pedestal upon a clique of socialites pose as patrons of the arts.” – Albert C. Barnes

However, those proposing the relocation of the Barnes collection insisted the move was not money-driven but rather, the only way for the foundation to survive. Over the years, the foundation failed to sustain itself and desperately needed funds to continue to operate. The problem was that while his suburban Beaux-Arts mansion in Merion served as a proper home for the Barnes Foundation for the earlier decades, it remained relatively inaccessible to the public.

While it held an impressive collection of work, its location made it challenging for people to come and appreciate it. To save the foundation from further neglect, they insisted that a move to a newer and larger facility in downtown Philadelphia was not only necessary but logical.

The ‘Art of the Steal’ vs. the “Truth”

But was it just a means to turn the collection into a major tourist-attraction that would line the pockets of those left in charge? The people who were against the move sure thought so, and they fueled so much outrage that in 2009, the documentary, “The Art of the Steal” was released. Directed by Don Argott, the film was about the controversial move of the Barnes Foundation and how it went against the stipulations of Barnes’ will. The film goes into detail about how the clauses in Barnes’ will were challenged and overcome.

“The Art of the Steal” was received with mixed emotions. The controversy over the film resulted in a Q&A session which, according to the director, had participants screaming at each other. The film went on to be distributed to over 100 theaters in North America and made available for online streaming. And in 2009, “The Art of the Steal” was named an Official Selection of the AFI Film Festival.

The chairman of the Barnes Foundation, Bernard C. Watson, responded to the film’s release by sending an editorial letter to The Philadelphia Inquirer. He claimed the film lacked “objectivity and perspective.” The Barnes Foundation was so determined to air their side of the story and gain public empathy on the move that they commissioned a film titled, “Barnes and Beyond: In the End, Truth Prevails.” The hour-long film tells the “untold story of how lies and legal battles were overcome” in the bitter dispute over the foundation’s relocation.

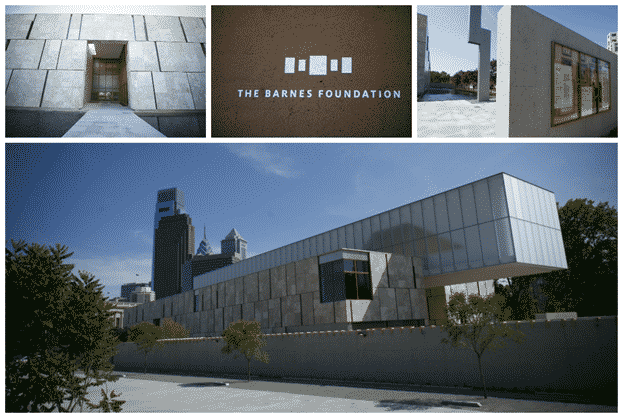

The Barnes Foundation would ultimately find a new home, designed by architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, which opened in 2012 in downtown Philadelphia. The state-of-the-art facility has a 12,000-square-foot gallery that houses one of the most comprehensive 9,000-piece collections of post-impressionist, impressionist, and early modern paintings with an estimated value of $20-$30 billion. To honor Barnes, the gallery has the same dimensions and layouts of the foundation’s original home in Merion.

“the advancement of education and the appreciation of the fine arts and horticulture” – The Barnes Foundation mission

![[Left] Kusama with her piece Dots Obsession, 2012, via AWARE, [Right] Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art) | Source: thecollector.com](https://www.artdex.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Left-Kusama-with-her-piece-Dots-Obsession-2012-via-AWARE-Right-Yayoi-Kusama-Courtesy-Whitney-Museum-of-American-Art-Source-thecollector.com--300x172.png)