On April 30, 2024, Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan debuted his exhibition at Gagosian Gallery’s NYC Chelsea location. The massive installation featured 24-karat gold panels, each meticulously marked with bullet holes. The problem? Cattelan’s show titled Sunday bore an uncanny resemblance to an exhibition that opened on the same day.

On the other side of Manhattan, British-American artist Anthony James’ unveiled his exhibition at Midtown East, sponsored by Opera Gallery during the Frieze New York art fair. Shots Fired showcased James’ signature style – one he has employed for over a decade. Since 2011, James has produced his “Bullet Series,” works that merge the physical impact of bullets with the reflective properties of metal – as seen in Portal Icosahedron (2011).

The juxtaposition of the undeniably similar exhibitions has sparked a legal dispute with James dispatching a five-page letter to Cattelan, claiming that Sunday constitutes a copyright violation as the similarities in the creative decision-making and fabrication of the artworks are beyond accidental. James says, “There’s no chance that he hasn’t seen them or that they haven’t come to his attention.”

Quoted as saying “The resemblance is uncanny. All I can say is good luck to both of us,” Cattelan has expressed surprise by the incident. Backed by Gagosian, the gallery has spoken for Cattelan to disagree with the allegations and insist that James’ claims have no merit. While James’ intention with his bullet series was to “create beauty through a violent act,” Cattelan describes his works marked by gunfire as a commentary on gun violence. Gagosian’s curator insists that the works present different meanings and maintains that Cattelan has never seen James’ work.

The art world is now left with the question, is this a case of intentional imitation or mere coincidence?

No Stranger to Controversy

Ironically, Cattelan announced his retirement in 2011, the same year James first introduced his distinctive bullet-marked technique. At the time, Cattelan’s retirement was perceived by many as a conceptual gesture, a prank consistent with his subversive humor and tendency to challenge the art world’s conventions. However, this narrative of finality and completion that would have allowed the art world to reflect on his entire oeuvre and provocative approach to art did not last.

Cattelan emerged from retirement in 2019 with his artwork Comedian, which featured a fresh banana duct-taped to a gallery wall. The installation created for Art Basel Miami Beach sparked widespread debate about the nature of art and value; it also became Cattelan’s first notable copyright controversy.

California-based artist Joe Morford claimed that Cattelan’s piece was a deliberate copy of his original artwork Banana and Orange (2001). The copyright case between Cattelan and Morford began in 2021 with Morford filing a pro se complaint in the Southern District of Florida. Both artworks featured a fruit affixed to a wall using adhesive material. Similar to claims of having never seen James’ “Bullet Series” works, Cattelan also insisted that he’d never heard of Morford.

While the two parties attempted to resolve the dispute through in-person mediation, they could not settle the matter. Ultimately, a US district judge ruled in Cattelan’s favor in 2023, determining that Morford could not provide sufficient evidence that Cattelan had directly copied Morford’s work. However, the court did note several undisputed facts, including that both works were “three-dimensional wall sculptures depicting bananas duct-taped to a vertical surface.” Both works also had similar orientations and presented viewers with the same perspective. One notable difference, however, was Cattelan’s use of a fresh banana; Morford’s work featured plastic fruit.

Examining Cases of Copyright Infringement in Artistic Expression

In the case of Morford vs. Cattelan, Morford argued that his original work had been posted online for about a decade before Cattelan’s piece. However, the court reasoned that a work’s presence on the internet is not enough to demonstrate access or the “reasonable opportunity to view” Morford’s copyrighted work, highlighted by the fact that Banana and Orange was not considered a significant work that attained a meaningful level of popularity.

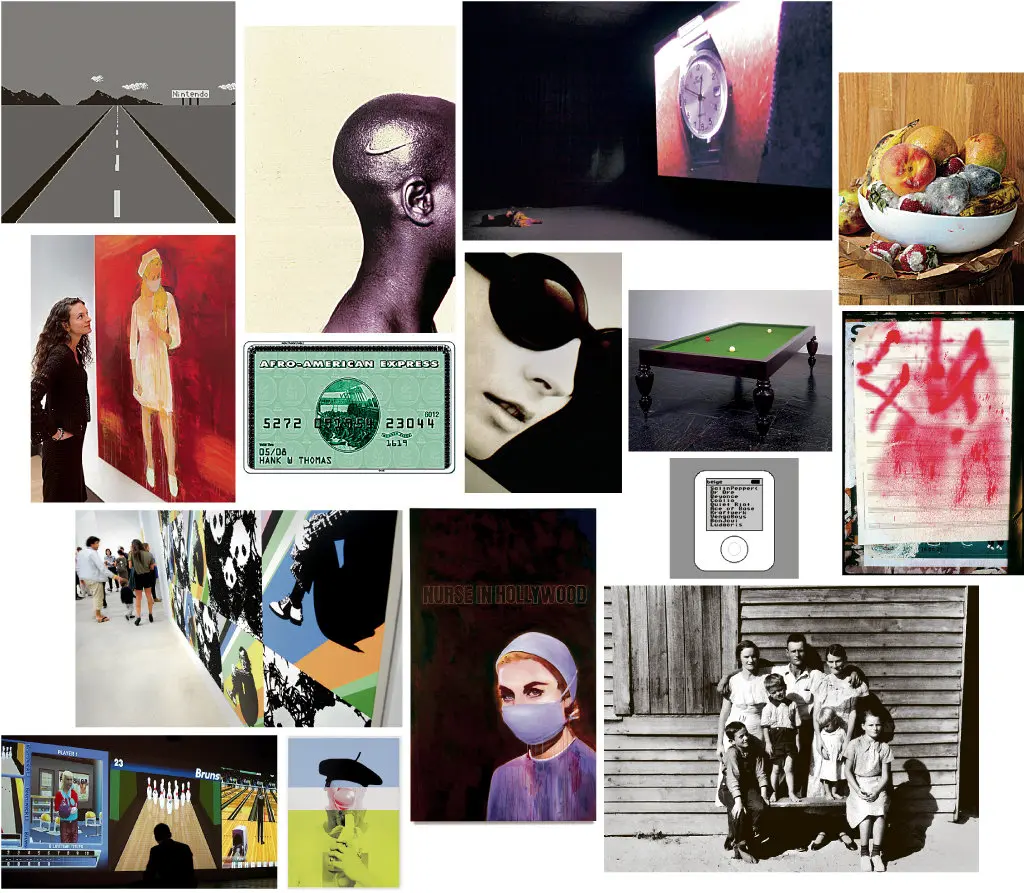

Cattelan’s copyright infringement controversies are certainly not the first for well-known artists. Lawsuits highlighting the contentious nature of copyright infringement and the related battles over the decades have forced the art world to engage in complex dialogue surrounding originality, appropriation, and fair use.

American artist Richard Prince has faced multiple high-profile lawsuits for his “appropriation art,” which have involved Prince taking images from pop culture and recontextualizing them in his own work. In the Patrick Cariou vs. Richard Prince case, the court found that most of Prince’s works in question were transformative enough to be considered fair use because they added new expression, meaning, or message beyond the original material.

Throughout his career, renowned artist Jeff Koons has been sued for copyright infringement; one notable case concluded with the court ruling that Koons had unlawfully copied a copyrighted photo by Art Rogers to model his sculpture. In a different copyright infringement case, the court ruled in favor of Koons after finding that his use of a copyrighted photograph was transformative and constituted fair use.

In cases settled outside of court, British artist Damien Hirst was sued by two artists who contended that the sculptor’s work bore striking resemblances to their works. Artist Robert Dixon accused Hirst of copying his geometric design, claiming Hirst’s use of similar patterns and color arrangements infringed on his copyright. Artist John LeKay alleged that Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull For the Love of God was a copy of his earlier works. LeKay, who knew Hirst personally, describes the shock of hearing Hirst had allegedly copied his idea as a “punch in the gut.”

Balancing Inspiration and Infringement

To those aware of both Hirst’s and LeKay’s works, it would seem that Hirst “improved” on LeKay’s bedazzled skull concept by using diamonds instead of Swarovski crystals. Those who compare the exhibitions of Cattelan and James will likely note that Cattelan’s installation is slightly more impressive for its use of 24-karat gold instead of stainless steel. Therefore, we ask – who deserves recognition and protection? The one who did it first or the one who did it better? Where do we draw the ethical boundaries on art appropriation?

While copyright exists automatically from the moment of creation, registering copyrights and using copyright notices can safeguard your reputation and legacy. Registration creates a public and legal record of your copyright claim, which can serve as evidence in an infringement lawsuit. Registering copyrights also provides significant benefits such as the ability to sue for statutory damages and recovery of attorney’s fees. Moreover, registered copyrights may deter potential infringers, providing a clear message that you’re serious about protecting your intellectual property and prepared to face them in court should they participate in the unauthorized use of your creative works.

The hard truth is that in many cases, the courts have sided with the artist accused of copyright infringement. As an artist, it’s discouraging to know that your copyright infringement claims won’t always work in your favor. Even with a registered copyright and use of copyright notices, another artist may convince the court that their work is transformative and fits within the fair use doctrine.

Pablo Picasso famously said, “Good artists copy, great artists steal.” However, artists shouldn’t just sit back and accept that, at some point, their original art may be replicated – no matter how flattered they may feel that their work is worthy of inspiration and consequently, imitation. As professional artists seek to make a living through their work, the reality is that creativity and commerce will intersect. Not only should artists understand the nuances of copyright and fair use to safeguard their own works but also prevent themselves from infringing on others.